Natural Resource Inventory and Assessment

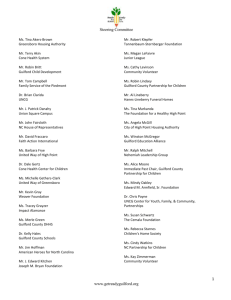

advertisement