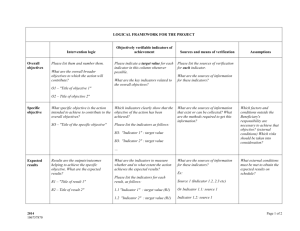

how do we know we are making a difference?

advertisement