UNCTAD/SDTE/TLB/4 13 March 2002 UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT

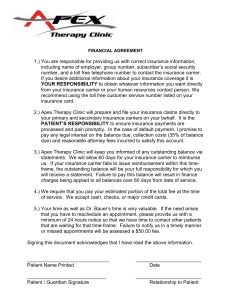

advertisement