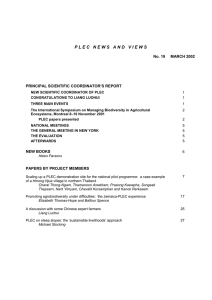

PLEC NEWS AND VIEWS The United Nations University

advertisement