The war at home - First World War overview

advertisement

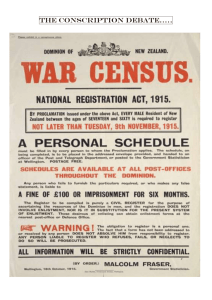

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/first-world-war-overview/defending-our-shores The war at home - First World War overview Page 5 of 9 The war at home Reading the casualty list Most New Zealanders responded to the war with great enthusiasm. But as it dragged on, newspaper editorials called for greater sacrifices. By 1917 war-weariness had set in. Things were at a stalemate. Casualty lists and food prices continued to rise. In July 1917 some called for New Zealand’s military commitment to be reduced. The conscription of married men aroused opposition; huge losses at Passchendaele in October 1917 caused morale to plummet. There was frustration at the time it took to bring to bear the resources of the United States, which had entered the war in April 1917. Newspapers remained sure of ultimate British victory, and there were no calls to bring New Zealand troops home. Anti-German hysteria Alleged (and sometimes actual) German atrocities in Europe fired indignation and anger towards all things German. A campaign in the main newspapers tried to root out anything possibly contaminated by German kultur. Growing casualty lists added to this public hysteria, and people of German descent became the target of abuse and harassment. Rumours of German spies and conspiracies abounded. George William von Zedlitz A perfect illustration of this anti-German hysteria was the experience of George William von Zedlitz. The German-born and English-educated von Zedlitz came to New Zealand in 1902 when he was appointed professor of modern languages at Victoria University College in Wellington. In addition to his academic duties, he was official translator to the New Zealand government between 1912 and 1914. On the outbreak of war von Zedlitz volunteered to return to Germany as a Red Cross worker. This created a backlash against him. The government introduced legislation to secure his removal from Victoria University College. The college council defended him but he was removed in October 1915 under the Alien Enemy Teachers Act. After the war von Zedlitz helped found the University Tutorial School and became well known as an adult education lecturer and as a broadcaster. In 1936 Victoria University College made him professor emeritus, and in the same year, he was elected to the senate of the University of New Zealand. He died in Lower Hutt in 1949. Conscription War census and conscription As the war dragged on, the seemingly endless toll in lives and maimed men undermined New Zealand’s ability to maintain the numbers required for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Despite public disapproval of those seen as shirkers, 69% of men eligible for military service had not volunteered by 1916. Only with conscription, introduced later that year, could New Zealand maintain its war effort. Some New Zealanders opposed conscription for a variety of reasons, and some were granted exemption, mainly on religious grounds. Exemption was generally frowned upon. About 2600 conscientious objectors were imprisoned for their beliefs. Some were forcibly sent to the front to break their resolve. Convicted objectors were denied voting rights for 10 years and barred from working for central or local government. http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/first-world-war/conscientious-objection Conscientious objection in the First World War Page 1 of 6 There are always supporters and opponents of a country fighting a war. As a nation, New Zealand took a full part in the First World War. More than 100,000 New Zealanders served overseas, and there was strong support for the war on the home front. But there were also people who opposed the war, for political, religious or moral reasons. Some of these people – conscientious objectors – paid a heavy price for their stance. Over by Christmas When the war broke out in 1914 men flocked in their thousands to answer the call to arms. By the end of the first week of the war 14,000 had enlisted. Few New Zealanders seemed opposed to the war. Despite confident claims that it would be 'over by Christmas', by 1916 the war appeared no closer to a conclusion. The seemingly endless toll in lives and maimed men began to impact on public sentiment. Newspaper editorials urged the public to accept the necessity of greater sacrifices if the war was to be won. Intensive campaigns to encourage enlistment failed to meet their targets; only 30% of men eligible for military service had volunteered. In 1916 conscription for military service was introduced to maintain New Zealand's supply of reinforcements. Only four MPs opposed its introduction. The Military Service Act 1916 initially imposed conscription on Pakeha only, but this was extended to Maori in June 1917. More than 30,000 conscripts had joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force by the end of the war. Objection to service By the end of 1916 conscientious objection to being conscripted for service had become a major issue. Those who objected did so for many reasons. Maori from iwi who had suffered as a result of imperial and settler government policies of the 1860s also resisted the call to fight for the British king. The authorities and general public usually dismissed these arguments; everyone was expected to do their bit for 'King and Country'. People could gain exemption from conscription on very limited grounds. By the end of the war only 73 objectors had been offered exemption, and 273 were in prison in New Zealand for refusing to serve. As a consequence of their actions, 2600 conscientious objectors lost their civil rights, including being denied voting rights for 10 years and being barred from working for government or local bodies. Military Service Act - conscientious objection in the First World War Page 2 of 6 Military Service Act Recruitment poster The Military Service Act 1916 introduced conscription, initially for Pakeha only. The act also made limited allowance for people who objected to serve. Only members of religious bodies that had, before the outbreak of war, declared military service 'contrary to divine revelation' could be exempted from service. Those excused had to be prepared to undertake alternative non-combatant service in New Zealand or overseas. Only Quakers, Christadelphians and Seventh-day Adventists met this qualification. No escape for the shirker Men eligible for military service who remained at large faced hostility from the wider community. Prime Minister William Massey made it clear that there would be 'no escape for the shirker'. Conscientious objectors received little sympathy from the Military Service Boards that were set up to administer conscription. Between September 1917 and October 1918, 170 objectors were sent overseas in non-combatant roles. Men like Archibald Baxter and Mark Briggs received military punishments. Many were beaten and abused for their stance. All objectors not considered genuine were eventually imprisoned, and some, such as the Labour MP Paddy Webb, were sentenced to hard labour. Socialist objection - conscientious objection in the First World War Page 3 of 6 Socialist and labour opposition to conscription 'Conscript wealth as well as men' Peter Fraser Many socialist and labour leaders criticised the First World War as an imperialist war and strongly opposed conscription. New Zealand workers, they argued, had no quarrel with German workers. The New Zealand Labour Party, founded in 1916, said that conscription should not be introduced unless it was accompanied by the conscription of wealth. In December 1916, party member (and future prime minister) Peter Fraser was arrested, charged and convicted of sedition for advocating the repeal of the Military Service Act. He served 12 months' imprisonment for the offence. Bob Semple, Tim Armstrong, Jim O'Brien and Paddy Webb, all future Labour cabinet ministers, also went to prison for their opposition to the war or conscription. 'You must do your duty' The war effort saw the government dispense with many established rights. When Bob Semple was imprisoned for 12 months after advising miners not to be 'lassoed by that Prussian octopus, conscription', he was denied a jury trial under the terms of the War Regulations. Irish opposition The British crushing of the Easter Rising in Ireland in 1916 made opposition to conscription an Irish nationalist issue. A number of the high-profile trade union leaders in New Zealand had strong Irish links and were reluctant to defend the British Empire. They also objected to fighting alongside an army that had executed Irish Nationalists in the wake of the rising. The West Coast trade unionist Jim (Briney) O'Brien highlighted this sentiment. Raised as a Catholic and of Irish descent, he initially opposed military conscription because he believed that while the workers fought, the capitalists prospered. His opposition to conscription grew as the conflict in Ireland intensified. The Coast's large Irish population meant sectarian issues were never far from the surface. Paddy Webb's victory in the 1913 Grey by-election was denounced by indignant Protestants as the result of an 'unholy alliance of socialists and Catholics'. Many on the Coast saw the conscription controversy after 1916 in pro-Irish/anti-British terms. Paddy Webb Paddy Webb suffered more than many of his fellow socialist and labour leaders as a result of the introduction of conscription. When the war broke out, Webb publicly stated that New Zealand should resist the Prussian onslaught on Flanders and Belgium but strongly opposed any suggestion of compelling men to fight. He opposed the national register of manpower compiled by the government in 1915 as the first step in preparation for military conscription. When conscription was introduced he demanded its immediate repeal, but he stopped short of advocating mass resistance to the Military Service Act. As a result, some union leaders and activists accused him of having lost his socialist sympathies. The first strike over conscription took place in late November 1916 when miners at Blackball on the West Coast sought repeal of the Military Service Act as well as a pay rise. Watersiders and miners began a go-slow against conscription in January 1917. When miners' leaders were arrested in April, all West Coast miners went on strike. Webb praised the miners' struggle against conscription as a battle for democratic freedom. He was arrested and charged with seditious utterance, and he served three months in prison. The strike ended at the end of April when Minister of Defence James Allen agreed no charges would be laid against those responsible for starting the go-slow or strikes. Its large Irish population and entrenched trade union tradition made the West Coast a stronghold for the anti-conscription movement. It also offered plenty of hiding places for men avoiding the ballot as they found many people willing to help them avoid arrest. A number of men were spirited off the Coast to Australia where conscription had not been introduced. Webb's opponents on the West Coast, including both local newspapers, had urged him to volunteer for service. They contrasted his 'cowardice' with the 'heroism' of T.E.Y. Seddon, the Member of Parliament for Westland (and son of former premier Richard John Seddon), who had volunteered in August 1915. As luck would have it, Webb was called up for military service in October 1917. He decided to seek a mandate from his electorate to stay home and resigned as MP, challenging the government to a by-election on the issue of conscription. The government refused, and Webb was returned unopposed. Declining a non-combatant role, Webb was court martialled and sentenced to two years' hard labour. His parliamentary seat was declared vacant in April 1918, and it was won in a byelection by another Labour member, Harry Holland. Webb spent two years tree planting on the Kaingaroa Plains, and he was deprived of his civil rights for 10 years. Pacifist objection - conscientious objection in the First World War Page 4 of 6 Pacifist and Christian socialists Some New Zealanders opposed the war on Christian or moral grounds. Others believed in peaceful methods of solving conflict. Some Christian socialists based their opposition to the war on what they saw as the egalitarian and anti-establishment message of Jesus Christ, who spoke against the religious authorities of his time. Pacifism – opposition to war or violence as a means of settling disputes – covered a spectrum of views. These ranged from the belief that international disputes should be peacefully resolved, to absolute opposition to the use of violence, or even force, under any circumstances. Many of the pacifists who opposed the Military Service Act did so because they believed that war, and indeed any use of force or coercion, was morally wrong. We will not cease: Archibald Baxter Archibald Baxter's 'We will not cease' cover Archibald Baxter (father of the poet James K. Baxter) is one of New Zealand's better-known pacifists from the First World War. His book We will not cease records his opposition to the war. In his words, the book is 'the record of my fight to the utmost against the military machine during the First World War. At that time to be a pacifist was to be in a distinct minority.' Baxter considered enlisting for the South African War (1899–1902) before becoming interested in pacifist ideals. He rejected the First World War both as a pacifist and as a Christian socialist. He was balloted for service and arrested soon after conscription was introduced in November 1916. He persuaded his family that the war was wrong, and six of the seven Baxter brothers would eventually go to prison for their beliefs. The seventh was married and therefore had a case for exemption. Baxter was denied exemption because he was not a member of a church that had, before the outbreak of war, declared military service 'contrary to divine revelation'. By the end of 1917 Baxter was in the prison attached to Trentham Military Camp near Wellington, and he was one of over 100 objectors being held in prison and prison camps throughout the country. 'Making an example' Minister of Defence James Allen was adamant that men such as Baxter should be sent to war. Many in the community shared his belief. In July 1917 Colonel H.R. Potter, the Trentham camp commander, decided to deal with the overcrowding in the prison by sending 14 of his most recalcitrant objectors to Britain aboard the troopship Waitemata. Among those sent were Archibald Baxter and his brothers Alexander and John. Mark Briggs refused to walk up the gangplank of the Waitemata and had to be dragged. Aboard the Waitemata the objectors were stripped, placed in uniform and locked in a small cabin with no open portholes. They were regularly abused by officers and volunteer soldiers. Upon arrival at Sling Camp in England, they refused to carry out gardening work and were placed in solitary confinement. Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, who commanded the New Zealand forces in Britain, wanted them confined, given field punishment and then sent into the trenches – even if they had to be carried on stretchers. In October 1917, 10 objectors were sent to Etaples in France and warned that they would be shot if they continued to refuse to submit. Several relented and agreed to become stretcher bearers, while three were sentenced to hard labour. Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell was determined to break the resolve of Archibald Baxter, Lawrence Kirwin, Henry Patton and Mark Briggs. They were subjected to repeated sentences of Field Punishment No. 1, part of which included what was known as 'the crucifixion'. This involved being tied to a post in the open, with their hands bound tightly behind their backs and their knees and feet bound. They were held in this position for up to four hours a day in all weathers. Baxter, Kirwin and Briggs survived this punishment only to be forced into the trenches. Baxter was sent to a part of the front that was being heavily shelled. He was beaten and denied food. In April 1918 he was taken to hospital in Boulogne, and he was diagnosed as having 'mental weakness and confusional insanity'. Three weeks later a British medical board confirmed the diagnosis of insanity, although it suggested that this may have been exaggerated so that Baxter could not be court martialled by the New Zealand army. He was taken to a British hospital for mentally disturbed soldiers, and he was sent home in August 1918. Along with Briggs, he was one of only two of the original 14 objectors to hold out to the end. Mark Briggs Mark Briggs was called up in the third conscription ballot in early 1917. He refused to serve on socialist grounds. His appeal was denied and on 23 March 1917, after he rejected an army medical examination in Palmerston North, he was escorted to Trentham Military Camp. Refusing all military orders to drill, he was court martialled and sentenced to 84 days' hard labour. During the seven weeks he spent in prison, he met future prime minister Peter Fraser. Upon arrival at Etaples in France in October 1917 he refused to walk, stand, salute or wear uniform. Field Punishment No. 1 failed to break his resolve, and he joined Archibald Baxter and Lawrence Kirwin in the trenches in February 1918. Every morning they were forced to walk 1000 yards up to the front line. Briggs refused. On the first day he was carried by sympathetic soldiers, but on the second day military policemen tied wire around his chest and dragged him to the front line, tearing his clothing and skin. At the line he was pulled through puddles of freezing water and told to 'Drown yourself, now, you bastard.' Dragged back to camp, he was denied medical treatment. In mid-April Briggs was returned to Etaples. It was now considered highly unlikely that he would be 'persuaded' to follow orders, and in June he was classified C2 (unfit for active service) due to muscular rheumatism. In early 1919 he was invalided back to New Zealand. He refused the soldier's wage that was offered to him. Punishing the objectors Punishment was considered an important part of breaking in objectors. Obviously the military authorities believed that if objection was made too easy then the war effort would suffer. Men like Baxter and Briggs were subjected to the most extreme measures, but all of those imprisoned faced a tough, carefully regulated plan of punishment designed to break their resolve. Those who didn't break after a month's imprisonment were court martialled at Trentham and sentenced to anything between 11 and 24 months' hard labour. Conditions in prison for objectors were harsh. Conversation was forbidden and so-called difficult prisoners were subject to solitary confinement. Work in the quarries was backbreaking. At the end of their sentence objectors could either be sent to the front or reimprisoned if they still refused to enlist. Maori objection - conscientious objection in the First World War Page 5 of 6 Maori resistance to conscription Native Contingent At the outbreak of war imperial policy did not allow 'native peoples' to fight in a war among Europeans. Permission was eventually granted for a Maori contingent to form part of New Zealand's war effort. A Native Contingent Committee co-ordinated Maori recruitment. The four Maori MPs, in particular Apirana Ngata and Maui Pomare, were key figures in this committee. The Native Contingent Committee had set a quota of 150 recruits every four weeks. This quickly became a struggle to achieve. In the second and third drafts that sailed in September 1915 and February 1916 only a third were Maori – the rest were mostly Niueans and Rarotongans. 'We have our own King' The Native Contingent Committee faced a lack of support from a significant sector of the Maori community. Many Maori from Taranaki, Ngati Maniapoto and the Tainui-Waikato regions did not respond to the call to fight for 'King and Country'. The events of the 1860s, when their land had been confiscated as punishment for being in rebellion against the British Crown, had left them questioning why they should now be expected to fight for the British. Te Puea Herangi Kingitanga leader Te Puea Herangi maintained that her grandfather, King Tawhiao, had forbidden Waikato to take up arms again when he made peace with the Crown in 1881. She was determined to uphold his call to Waikato to 'lie down' and 'not allow blood to flow from this time on'. Te Puea maintained that Waikato had 'its own King' and didn't need to 'fight for the British King'. If land that had been confiscated was returned, then perhaps Waikato might reconsider its position. Maori blood cries out for utu In trying to meet their quota some members of the Native Contingent Committee and the government tried to shame Maori into participation. Ngata pointed out that every letter he received from soldiers at the front asked for more reinforcements. His waiata 'Te Ope Tuatahi' praised those iwi who had already contributed and drew attention to those who had yet to serve. Defence Minister James Allen made a direct appeal to Waikato pride in late 1916 when he urged Waikato Maori to 'save New Zealand from the fate of Belgium, and their women from being the sport of German bayonets'. At Waahi pa in November 1916 Allen told Waikato that 'if you fail now you and your tribes can never rest in honour in the days to come'. Conscription extended to Maori When conscription for military service was introduced in 1916 it was initially imposed on Pakeha only. Pomare and Ngata wanted it applied to Maori as a matter of self-respect. Maori blood had been spilt overseas, and Maori had a duty to respond; utu was required. Having failed to persuade Waikato, Allen supported the extension of conscription to Maori in June 1917 but decided to apply it to the Waikato–Maniapoto land district only. As other tribes had volunteered and filled the first two contingents, some in official circles considered the application of conscription in this way to be fair. Allen knew that this was also where the heart of the resistance lay. The inclusion of Ngati Maniapoto caused an outrage. Their rate of enlistment was much higher than that of Pomare's own people from Taranaki, who were excluded from the ballot. There was a feeling that Pomare was exacting revenge on Ngati Maniapoto–Waikato for the defeats Taranaki had suffered at their hands in the 19th century. To make matters worse, the government compiled the register for the ballot using information that had been gathered in complete confidence at the 1916 Census. This was a violation of the law but was apparently agreed to by the Maori MPs. Waikato resist Te Puea offered refuge at Te Paina pa (Mangatawhiri) for men who chose to ignore the ballot. Waikato were denounced as 'seditious traitors', while the revelation that Te Puea's grandfather had a German surname – Searancke – confirmed her status as a 'German sympathiser'. Te Puea pointed out that the Searanckes were at least four generations removed from their German origins and that the British royal family itself was German. Rua Kenana, 1908 Colonel Patterson of the Auckland Military District wanted Te Puea punished and planned to goad her into making anti-conscription statements in front of reliable witnesses. This would allow her to be prosecuted under the War Regulations for 'inciting men not to enlist'. Others favoured a more cautious approach, fearing such action would simply increase her prestige. The government knew that under Te Puea's leadership the campaign was at least non-violent. In 1916 two Maori had been shot and killed by police attempting to arrest the Tuhoe leader Rua Kenana at Maungapohatu, in part for his active discouragement of Maori recruitment. The government did not want a repetition of this bloodshed. Maui Pomare advised Allen that those at Te Paina were 'merely waiting to be taken to jail' and suggested a minimal show of force would suffice. Arresting and punishing the objectors A crowd greeted police when they arrived at Te Paina on 13 July 1917. They were escorted into the meeting house where they read out the names of those to be arrested. Nobody moved. Te Puea made it clear that she would not co-operate. The police waded into the crowd and began arresting men they believed to be on their list. Mistakes were made. Te Puea's future husband, 16-year-old Rawiri Katipa, was mistaken for his older brother; a 60-year-old was also arrested. Each of the seven men selected had to be carried out of the meeting house. King Te Rata's 16-year-old brother, Te Rauangaanga, was also seized. Police stepped over the King's personal flag, which had been protectively laid before Te Rauangaanga, and this caused great offence to those gathered. Te Puea intervened, calming the shocked onlookers and blessing those seized. She told the police to let the government know she was afraid of no law or anything else 'excepting the God of my ancestors'. The prisoners were taken to the army training camp at Narrow Neck, Auckland. Those who refused to wear the army uniform were subjected, like other objectors, to severe military punishments, including 'dietary punishments' (being fed only bread and water) and being supplied with minimal bedding. When this failed, some were sentenced to two years' hard labour at Mount Eden prison. Te Puea supported those who had been arrested by bringing them food (which never seemed to reach the inmates) and attempting to visit those in prison. She was a source of great inspiration to the prisoners. One of those detained, Mokona, described how Te Puea would sit outside the prison and when men went to the whare mimi (toilet) they were able to catch a glimpse of her. This was enough to make them want to 'invent an excuse to go to the whare mimi. The fact that she was there gave us heart to continue.' Resistance maintained to the end Maui Pomare decided to make a direct appeal to Tainui and persuade them to abandon their resistance. This personal approach failed dismally. The fact that their men were now in prison merely hardened Tainui resolve. When Pomare attended a hui at Waahi pa in 1918, he was greeted with abusive haka composed specially for his visit. This culminated in the act of whakapohane (performers baring their buttocks in contempt for an unwelcome visitor). Only a handful of Tainui men were ever put into uniform, and none of the Tainui conscripts were sent overseas. By 1919 only 74 Maori conscripts had gone to camp out of a total of 552 men called. When the war ended, those Maori in training were sent home, and all outstanding warrants were cancelled. What to do with the defaulters already in custody was a little trickier. Despite the military's objection, Cabinet decided in May 1919 to release all Maori prisoners. This decision was never made public because the government was determined not to treat other defaulters so leniently. The imposition of conscription on the Waikato and Ngati Maniapoto people had long-lasting effects. The breach it caused was probably only restored with the Tainui Treaty settlement in 1995.