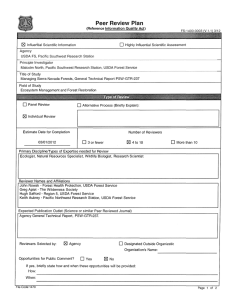

Major Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the United States: 2013

advertisement