Electric Forces and Electric Fields Chapter 15

advertisement

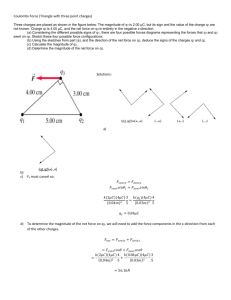

Chapter 15 Electric Forces and Electric Fields Quick Quizzes 1. (b). Object A must have a net charge because two neutral objects do not attract each other. Since object A is attracted to positively-charged object B, the net charge on A must be negative. 2. (b). By Newton’s third law, the two objects will exert forces having equal magnitudes but opposite directions on each other. 3. (c). The electric field at point P is due to charges other than the test charge. Thus, it is unchanged when the test charge is altered. However, the direction of the force this field exerts on the test change is reversed when the sign of the test charge is changed. 4. (a). If a test charge is at the center of the ring, the force exerted on the test charge by charge on any small segment of the ring will be balanced by the force exerted by charge on the diametrically opposite segment of the ring. The net force on the test charge, and hence the electric field at this location, must then be zero. 5. (c) and (d). The electron and the proton have equal magnitude charges of opposite signs. The forces exerted on these particles by the electric field have equal magnitude and opposite directions. The electron experiences an acceleration of greater magnitude than does the proton because the electron’s mass is much smaller than that of the proton. 6. (a). The field is greatest at point A because this is where the field lines are closest together. The absence of lines at point C indicates that the electric field there is zero. 7. (c). When a plane area A is in a uniform electric field E, the flux through that area is Φ E = EA cosθ where θ is the angle the electric field makes with the line normal to the plane of A. If A lies in the xy-plane and E is in the z-direction, then θ = 0° and Φ E = EA = ( 5.00 N C ) ( 4.00 m 2 ) = 20.0 N ⋅ m 2 C . 8. (b). If θ = 60° in Quick Quiz 15.7 above, then Φ E = EA cosθ = ( 5.00 N C ) ( 4.00 m 2 ) cos ( 60° ) = 10.0 N ⋅ m 2 C 9. (d). Gauss’s law states that the electric flux through any closed surface is equal to the net enclosed charge divided by the permittivity of free space. For the surface shown in Figure 15.28, the net enclosed charge is Q = −6 C which gives Φ E = Q ∈0 = − ( 6 C ) ∈0 . 1 2 10. CHAPTER 15 (b) and (d). Since the net flux through the surface is zero, Gauss’s law says that the net change enclosed by that surface must be zero as stated in (b). Statement (d) must be true because there would be a net flux through the surface if more lines entered the surface than left it (or vise-versa). Electric Forces and Electric Fields 3 Answers to Even Numbered Conceptual Questions 2. Conducting shoes are worn to avoid the build up of a static charge on them as the wearer walks. Rubber-soled shoes acquire a charge by friction with the floor and could discharge with a spark, possibly causing an explosive burning situation, where the burning is enhanced by the oxygen. 4. Electrons are more mobile than protons and are more easily freed from atoms than are protons. 6. No. Object A might have a charge opposite in sign to that of B, but it also might be neutral. In this latter case, object B causes object A to be polarized, pulling charge of one sign to the near face of A and pushing an equal amount of charge of the opposite sign to the far face. Then the force of attraction exerted by B on the induced charge on the near side of A is slightly larger than the force of repulsion exerted by B on the induced charge on the far side of A. Therefore, the net force on A is toward B. +++ + + B + + +++ + +A + 8. If the test charge was large, its presence would tend to move the charges creating the field you are investigating and, thus, alter the field you wish to investigate. 10. She is not shocked. She becomes part of the dome of the Van de Graaff, and charges flow onto her body. They do not jump to her body via a spark, however, so she is not shocked. 12. An electric field once established by a positive or negative charge extends in all directions from the charge. Thus, it can exist in empty space if that is what surrounds the charge. 14. No. Life would be no different if electrons were positively charged and protons were negatively charged. Opposite charges would still attract, and like charges would still repel. The designation of charges as positive and negative is merely a definition. 16. The antenna is similar to a lightning rod and can induce a bolt to strike it. A wire from the antenna to the ground provides a pathway for the charges to move away from the house in case a lightning strike does occur. 18. (a) If the charge is tripled, the flux through the surface is also tripled, because the net flux is proportional to the charge inside the surface. (b) The flux remains constant when the volume changes because the surface surrounds the same amount of charge, regardless of its volume. (c) The flux does not change when the shape of the closed surface changes. (d) The flux through the closed surface remains unchanged as the charge inside the surface is moved to another location inside that surface. (e) The flux is zero because the charge inside the surface is zero. All of these conclusions are arrived at through an understanding of Gauss’s law. 20. (a) –Q (b) +Q (c) 0 (d) 0 (e) +Q (See the discussion of Faraday’s ice-pail experiment in the textbook.) 4 22. CHAPTER 15 The magnitude of the electric force on the electron of charge e due to a uniform electric G field E is F = eE . Thus, the force is constant. Compare this to the force on a projectile of mass m moving in the gravitational field of the Earth. The magnitude of the gravitational force is mg. In both cases, the particle is subject to a constant force in the vertical direction and has an initial velocity in the horizontal direction. Thus, the path will be the same in each case—the electron will move as a projectile with an acceleration in the vertical direction and constant velocity in the horizontal direction. Once the electron leaves the region between the plates, the electric field disappears, and the electron continues moving in a straight line according to Newton’s first law. Electric Forces and Electric Fields Answers to Even Numbered Problems 2. 5.71 × 1013 C 4. F = 1.91( ke q2 a2 ) along the diagonal toward the negative charge 6. 2.25 × 10 −9 N m 8. 5.08 m 10. F6 = 46.7 N ( left ) , F1.5 = 157 N ( right ) , F−2 = 111 N ( left ) 12. 3.89 × 10 −7 N at 11.3° below + x axis 14. x = 0.634 d , stable if third bead has positive charge 16. 1.45 m beyond the –3.00 nC charge 18. (a) 2.00 × 107 N C to the right 20. (a) 5.27 × 1013 m s 2 22. 1.63 × 10 4 N C directed opposite to the proton’s velocity 24. 1.88 × 10 3 N C at 4.40° below + x axis 26. at y = + 0.85 m 28. (a) 34. (a) zero 36. ~ 1 µm 38. (a) 40. (a) –55.7 nC (b) negative, with a spherically symmetric distribution 42. 5.65 × 10 5 N ⋅ m 2 C 48. (a) 8.2 × 10 −8 N 50. 5.25 µ C q1 q2 = − 1 3 2.0 × 10 6 N ⋅ m 2 C (b) (b) 40.0 N to the left 5.27 × 10 5 m s (b) q2 > 0, q1 < 0 (b) 1.8 × 10 6 N C (b) 0 (b) 2.2 × 10 6 m s (c) 1.1 × 10 5 N C 5 6 CHAPTER 15 3.43 µ C 52. (a) downward 54. 2.51 × 10 −10 56. (a) 0.307 s (b) Yes, the absence of gravity produces a 2.28% difference. 60. (d) 62. 2.0 µ C 64. (a) (b) JG E = 0 at x = +9.47 m, y = 0. 37.0° or 53.0° (b) 1.66 × 10 −7 s and 2.21 × 10 −7 s Electric Forces and Electric Fields 7 Problem Solutions 15.1 Since the charges have opposite signs, the force is one of attraction . Its magnitude is F= 15.2 k e q1 q2 r2 −9 −9 N ⋅ m 2 ( 4.5 × 10 C )( 2.8 × 10 C ) = 8.99 × 109 = 1.1 × 10 −8 N 2 2 C ( 3.2 m ) The electrical force would need to have the same magnitude as the current gravitational force, or ke q2 M m = G E 2 moon 2 r r q= giving GME mmoon ke This yields q= 15.3 F= ( 6.67 × 10 −11 N ⋅ m 2 kg 2 )( 5.98 × 10 24 kg )( 7.36 × 10 22 kg ) 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C 9 2 2 k e ( 2 e )( 79 e ) r2 2 ( 158 ) ( 1.60 × 10 −19 C ) 9 N⋅m = 8.99 × 10 = 91 N 2 C2 ( 2.0 × 10−14 m ) 2 ( repulsion ) = 5.71 × 1013 C 8 15.4 CHAPTER 15 F1 = F2 = and and F3 = ke q 2 (a 2 ) 2 = ur F1 2 ke q 2a2 k q ke q kq + e 2 ( 0.707 ) = 1.35 e 2 2 2a a a ΣFy = F1 + F3 sin 45° = ke q2 ke q2 ke q2 + = 0.707 1.35 ( ) 2 a2 2a2 a ( ΣFx ) 2 ( ) + ΣFy 2 2 = 1.91 2 2 +q a 2 ur F3 45° a ur F2 ΣFy ke q2 −1 and θ = tan −1 = tan ( 1) = 45° 2 a F Σ x G k q2 F R = 1.91 e 2 along the diagonal toward the negative charge a so (a) ke q a2 2 q a r ΣFx = F2 + F3 cos 45° = FR = 15.5 q The attractive forces exerted on the positive charge by the negative charges are shown in the sketch and have magnitudes F= k 2e 2 e( ) r2 N ⋅ m2 = 8.99 × 10 9 C2 −19 2 4 ( 1.60 × 10 ) = 36.8 N 2 ( 5.00 × 10 −15 m ) (b) The mass of an alpha particle is m = 4.002 6 u , where u = 1.66 × 10 −27 kg is the unified mass unit. The acceleration of either alpha particle is then a= F 36.8 N = = 5.54 × 10 27 m s 2 m 4.002 6 ( 1.66 × 10 −27 kg ) q Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.6 The attractive force between the charged ends tends to compress the molecule. Its magnitude is −19 2 k ( 1e ) N ⋅ m 2 ( 1.60 × 10 C ) F = e 2 = 8.99 × 109 = 4.89 × 10 −17 N . 2 2 − 6 r C ( 2.17 × 10 m ) 2 The compression of the “spring” is x = ( 0.010 0 ) r = ( 0.010 0 ) ( 2.17 × 10 −6 m ) = 2.17 × 10 −8 m , so the spring constant is k = 15.7 F 4.89 × 10 −17 N = = 2.25 × 10 −9 N m x 2.17 × 10 −8 m 1.00 g of hydrogen contains Avogadro’s number of atoms, each containing one proton and one electron. Thus, each charge has magnitude q = N A e . The distance separating these charges is r = 2 RE , where RE is Earth’s radius. Thus, F= ( ke N A e ( 2 RE ) ) 2 2 N ⋅ m2 = 8.99 × 10 9 C2 15.8 2 The magnitude of the repulsive force between electrons must equal the weight of an electron, Thus, k e e 2 r 2 = me g or 15.9 −19 23 ( 6.02 × 10 )( 1.60 × 10 C ) = 5.12 × 10 5 N 2 6 4 ( 6.38 × 10 m ) k e2 r= e = me g ( 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C )(1.60 × 10 C ) ( 9.11 × 10 kg )( 9.80 m s ) 9 2 −31 2 −19 2 2 = 5.08 m (a) The spherically symmetric charge distributions behave as if all charge was located at the centers of the spheres. Therefore, the magnitude of the attractive force is F= k e q1 q2 r2 −9 −9 N ⋅ m 2 ( 12 × 10 C )( 18 × 10 C ) = 8.99 × 109 = 2.2 × 10 −5 N 2 2 C ( 0.30 m ) 9 10 CHAPTER 15 (b) When the spheres are connected by a conducting wire, the net charge qnet = q1 + q2 = −6.0 × 10 −9 C will divide equally between the two identical spheres. Thus, the force is now F= k e ( qnet 2 ) r2 2 2 −6.0 × 10 −9 C ) 9 N⋅m ( = 8.99 × 10 C 2 4 ( 0.30 m )2 2 or F = 9.0 × 10 −7 N (repulsion) 15.10 The forces are as shown in the sketch at the right. +6.00 mC ur ur F2 F1 ur ur +1.50 mC F1 F2 2.00 mC ur ur F3 F3 3.00 cm F1 = F2 = F3 = 2.00 cm 2 6.00 × 10 −6 C )( 1.50 × 10 −6 C ) k e q1 q2 9 N⋅m ( = 8.99 × 10 = 89.9 N 2 r122 C2 ( 3.00 × 10-2 m ) ke q1 q3 r132 ke q2 q3 r232 2 6.00 × 10 −6 C )( 2.00 × 10 −6 C ) 9 N⋅m ( = 8.99 × 10 = 43.2 N 2 C2 ( 5.00 × 10-2 m ) −6 −6 N ⋅ m 2 ( 1.50 × 10 C )( 2.00 × 10 C ) = 8.99 × 109 = 67.4 N 2 C2 ( 2.00 × 10-2 m ) The net force on the 6 µ C charge is F6 = F1 − F2 = 46.7 N (to the left) The net force on the 1.5 µ C charge is F1.5 = F1 + F3 = 157 N (to the right) The net force on the −2 µ C charge is F−2 = F2 + F3 = 111 N (to the left) 11 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.11 ur 5.00 nC 6.00 nC F6 m q ur 0.100 0.300 m ur F 3 FR 3.00 nC In the sketch at the right, FR is the resultant of the forces F6 and F3 that are exerted on the charge at the origin by the 6.00 nC and the –3.00 nC charges respectively. 2 6.00 × 10 −9 C )( 5.00 × 10 −9 C ) 9 N⋅m ( F6 = 8.99 × 10 2 C2 ( 0.300 m ) = 3.00 × 10 −6 N −9 −9 N ⋅ m 2 ( 3.00 × 10 C )( 5.00 × 10 C ) = 1.35 × 10 −5 N F3 = 8.99 × 109 2 2 C 0.100 m ( ) The resultant is FR = F 2 + ( F3 ) = 1.38 × 10 −5 N at θ = tan −1 3 F6 = 77.5° G FR = 1.38 × 10 −5 N at 77.5° below − x axis Consider the arrangement of charges shown in the sketch at the right. The distance r is r= 2 2 ( 0.500 m ) + ( 0.500 m ) = 0.707 m The forces exerted on the 6.00 nC charge are N ⋅ m ( 6.00 × 10 C )( 2.00 × 10 F2 = 8.99 × 109 2 C2 ( 0.707 m ) 2 −9 −9 C) 3.00 nC 0.500 m 15.12 2 0.500 m or ( F6 ) ur F2 r 45.0° 0.500 m r 45.0° 6.00 nC 2.00 nC = 2.16 × 10 −7 N and 2 6.00 × 10 −9 C )( 3.00 × 10 −9 C ) 9 N⋅m ( F3 = 8.99 × 10 = 3.24 × 10 −7 N 2 2 C 0.707 m ( ) ur F3 12 CHAPTER 15 Thus, ΣFx = ( F2 + F3 ) cos 45.0° = 3.81 × 10 −7 N and ΣFy = ( F2 − F3 ) sin 45.0° = −7.63 × 10 −8 N The resultant force on the 6.00 nC charge is then FR = or 15.13 ( ΣFx ) 2 ( ) + ΣFy 2 ΣFy = 3.89 × 10 −7 N at θ = tan −1 ΣFx = − 11.3° G FR = 3.89 × 10 −7 N at 11.3° below +x axis The forces on the 7.00 µC charge are shown at the right. y 2 7.00 × 10 −6 C )( 2.00 × 10 −6 C ) 9 N⋅m ( F1 = 8.99 × 10 2 C2 ( 0.500 m ) = 0.503 N −6 −6 N ⋅ m 2 ( 7.00 × 10 C )( 4.00 × 10 C ) F2 = 8.99 × 109 2 C2 ( 0.500 m ) + 7.00 mC ur F2 60.0° x + 0.500 m 2.00 mC 4.00 mC = 1.01 N Thus, ΣFx = ( F1 + F2 ) cos 60.0° = 0.755 N and ΣFy = ( F1 − F2 ) sin 60.0° = −0.436 N The resultant force on the 7.00 µC charge is FR = or ( ΣFx ) 2 ( ) + ΣFy 2 ΣFy = 0.872 N at θ = tan −1 = −30.0° ΣFx G FR = 0.872 N at 30.0° below the +x axis ur F1 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.14 13 Assume that the third bead has charge Q and is located at 0 < x < d . Then the forces exerted on it by the +3q charge and by the +1q charge have magnitudes F3 = k e Q ( 3q ) x 2 and F1 = keQ ( q ) (d − x) 2 respectively These forces are in opposite directions, so charge Q is in equilibrium if F3 = F1 . This gives 3 ( d − x ) = x 2 , and solving for x, the equilibrium position is seen to be 2 x= d = 0.634 d 1+1 3 This is a position of stable equilibrium if Q > 0 . In that case, a small displacement from the equilibrium position produces a net force directed so as to move Q back toward the equilibrium position. 15.15 Consider the free-body diagram of one of the spheres given at the right. Here, T is the tension in the string and Fe is the repulsive electrical force exerted by the other sphere. mg ΣFy = 0 ⇒ T cos 5.0° = mg , or T = cos 5.0° ΣFx +y 5.0° ur Fe = 0 ⇒ Fe = T sin 5.0° = mg tan 5.0° q = ( 2 L sin 5.0° ) ke q2 ( 2 L sin 5.0° ) 2 = mg tan 5.0° and yields mg tan 5.0° ke = 2 ( 0.300 m ) sin 5.0° ( 0.20 × 10 −3 +x ur mg At equilibrium, the distance separating the two spheres is r = 2 L sin 5.0° . Thus, Fe = mg tan 5.0° becomes ur T kg )( 9.80 m s 2 ) tan 5.0° 8.99 × 109 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 = 7.2 nC 14 15.16 CHAPTER 15 6.00 nC 3.00 nC The required position is shown in the sketch at the right. Note that this places q closer to the smaller charge, which will allow the two forces to cancel. Requiring that ur F3 q ur F6 x 0.600 m F6 = F3 gives k e ( 6.00 nC ) q ( x + 0.600 m ) = 2 k e ( 3.00 nC ) q 2 , or 2 x 2 = ( x + 0.600 m ) x2 Solving for x gives the equilibrium position as x= 15.17 0.600 m = 1.45 m beyond the − 3.00 nC charge 2 −1 For the object to “float” it is necessary that the electrical force support the weight, or qE = mg 15.18 −6 qE ( 24 × 10 C ) ( 610 N C ) m= = = 1.5 × 10 −3 kg 2 g 9.8 m s or +6.00 mC q1 (a) Taking to the right as positive, the resultant electric field at point P is given by ur E2 P 2.00 cm ur E3 +1.50 mC ur q2 E1 1.00 cm 3.00 cm ER = E1 + E3 − E2 = k e q1 2 1 r + k e q3 2 3 r − k e q2 r22 N ⋅ m2 = 8.99 × 109 C2 6.00 × 10 −6 C 2.00 × 10 −6 C 1.50 × 10 −6 C + − 2 2 2 ( 0.020 0 m ) ( 0.030 0 m ) ( 0.010 0 m ) This gives ER = + 2.00 × 107 N C G or E R = 2.00 × 107 N C to the right G G (b) F = qE R = ( −2.00 × 10 −6 C )( 2.00 × 107 N C ) = −40.0 N G or F = 40.0 N to the left 2.00 mC q3 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.19 15 We shall treat the concentrations as point charges. Then, the resultant field consists of two contributions, one due to each concentration. The contribution due to the positive charge at 3 000 m altitude is E+ = k e 2 9 N ⋅ m ( 40.0 C ) = × = 3.60 × 10 5 N C 8.99 10 C 2 ( 1 000 m )2 r2 q ( downward ) The contribution due to the negative charge at 1 000 m altitude is E− = k e 2 9 N ⋅ m ( 40.0 C ) = × = 3.60 × 10 5 N C 8.99 10 C 2 ( 1 000 m )2 r2 q ( downward ) The resultant field is then G G G E = E + + E − = 7.20 × 10 5 N C ( downward ) 15.20 (a) The magnitude of the force on the electron is F = q E = eE , and the acceleration is −19 F eE ( 1.60 × 10 C ) ( 300 N C ) = = = 5.27 × 1013 m s 2 a= −31 9.11 × 10 kg me me (b) v = v0 + at = 0 + ( 5.27 × 1013 m s 2 )( 1.00 × 10 −8 s ) = 5.27 × 10 5 m s 15.21 If the electric force counterbalances the weight of the ball, then qE = mg 15.22 or −3 2 mg ( 5.0 × 10 kg )( 9.8 m s ) E= = = 1.2 × 10 4 N C −6 q 4.0 × 10 C The force an electric field exerts on a positive change is in the direction of the field. Since this force must serve as a retarding force and bring the proton to rest, the force and hence the field must be in the direction opposite to the proton’s velocity . The work-energy theorem, Wnet = KE f − KEi , gives the magnitude of the field as − ( qE ) ∆x = 0 − KEi or E= KEi 3.25 × 10 −15 J = = 1.63 × 10 4 N C q ( ∆x ) ( 1.60 × 10 -19 C ) ( 1.25 m ) −19 F qE ( 1.60 × 10 C ) ( 640 N C ) a= = = = 6.12 × 1010 m s 2 m mp 1.673 × 10 -27 kg (a) (b) t = 1.20 × 10 6 m s ∆v = = 1.96 × 10 −5 s = 19.6 µ s a 6.12 × 1010 m s 2 ∆x = (c) v 2f − v02 (d) KE f = 2 6 10 2 11.8 m 2 1 1 mp v 2f = ( 1.673 × 10 −27 kg )( 1.20 × 106 m s ) = 1.20 × 10 −15 J 2 2 q1 = 3.00 nC The altitude of the triangle is h = ( 0.500 m ) sin 60.0° = 0.433 m 00 15.24 2a (1.20 × 10 m s ) − 0 = = 2 ( 6.12 × 10 m s ) m 15.23 CHAPTER 15 0.5 16 and the magnitudes of the fields due to each of the charges are q2 = 8.00 nC E1 = 9 2 2 −9 k e q1 ( 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C )( 3.00 × 10 C ) = 2 h2 ( 0.433 m ) 60.0° 0.250 m = 144 N C 9 2 2 −9 k e q2 ( 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C )( 8.00 × 10 C ) E2 = 2 = = 1.15 × 10 3 N C 2 r2 0.250 m ( ) and E3 = k e q3 r32 ( 8.99 × 10 = 9 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 )( 5.00 × 10 −9 C ) ( 0.250 m ) 2 = 719 N C h ur E2 ur ur E q2 = 5.00 nC E1 3 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 17 Thus, ΣEx = E2 + E3 = 1.87 × 10 3 N C and ΣEy = −E1 = −144 N C giving ER = ( ΣEx ) 2 ( + ΣEy ) 2 = 1.88 × 10 3 N C and θ = tan −1 ( ΣEy ΣEx ) = tan −1 ( −0.0769 ) = −4.40° JG Hence E R = 1.88 × 10 3 N C at 4.40° below the +x axis 15.25 From the symmetry of the charge distribution, students should recognize that the resultant electric field at the center is q ur E2 ur E1 30° G ER = 0 30° ur E3 If one does not recognize this intuitively, consider: G G G G E R = E1 + E 2 + E 3 , so Ex = E1x − E2 x = ke q r 2 q cos 30° − ke q r2 cos 30° = 0 and Ey = E1 y + E2 y − E3 = Thus, ER = Ex2 + Ey2 = 0 ke q r 2 sin 30° + ke q r 2 sin 30° − ke q r2 =0 q 18 15.26 CHAPTER 15 If the resultant field is to be zero, the contributions of the two charges must be equal in magnitude and must have opposite directions. This is only possible at a point on the line between the two negative charges. q1 = 9.0 mC r1 6.0 m Assume the point of interest is located on the y-axis at − 4.0 m < y < 6.0 m . Then, for equal magnitudes, k e q1 r12 = k e q2 r22 or 9.0 µ C ( 6.0 m − y ) Solving for y gives y + 4.0 m = 15.27 2 = ur E1 ur E2 y +x 4.0 m 8.0 µ C ( y + 4.0 m ) r2 2 q2 = 8.0 mC 8 ( 6.0 m − y ) , or y = + 0.85 m 9 If the resultant field is zero, the +y contributions from the two charges must r1 = d 1.0 m be in opposite directions and also have +x ur ur equal magnitudes. Choose the line q q E2 E1 1 = 2.5 mC 2 = 6.0 mC connecting the charges as the x-axis, with r2 = 1.0 m + d the origin at the –2.5 µC charge. Then, the two contributions will have opposite directions only in the regions x < 0 and x > 1.0 m . For the magnitudes to be equal, the point must be nearer the smaller charge. Thus, the point of zero resultant field is on the x-axis at x < 0 . Requiring equal magnitudes gives Thus, (1.0 m + d ) k e q1 2 1 r = k e q2 2 2 r or 2.5 µ C 6.0 µ C = 2 2 d ( 1.0 m + d ) 2.5 =d 6.0 Solving for d yields d = 1.8 m , 15.28 or 1.8 m to the left of the − 2.5 µ C charge The magnitude of q2 is three times the magnitude of q1 because 3 times as many lines emerge from q2 as enter q1 . (a) Then, q1 q2 = − 1 3 q2 = 3 q1 Electric Forces and Electric Fields (b) 19 q2 > 0 because lines emerge from it, and q1 < 0 because lines terminate on it. 15.29 Note in the sketches at the right that electric field lines originate on positive charges and terminate on negative charges. The density of lines is twice as great for the −2 q charge in (b) as it is for the 1q charge in (a). 2q q>0 (a) 15.30 15.31 (b) Rough sketches for these charge configurations are shown below. +1 mC 2 mC (a) (b) (a) The sketch for (a) is shown at the right. Note that four times as many lines should leave q1 as emerge from q2 although, for clarity, this is not shown in this sketch. (b) The field pattern looks the same here as that shown for (a) with the exception that the arrows are reversed on the field lines. 2 mC +1 mC (c) q1 = 4q2 q2 20 15.32 CHAPTER 15 (a) In the sketch for (a) at the right, note that there are no lines inside the sphere. On the outside of the sphere, the field lines are uniformly spaced and radially outward. (b) In the sketch for (b) above, note that the lines are (a) (b) perpendicular to the surface at the points where they emerge. They should also be symmetrical about the symmetry axes of the cube. The field is zero inside the cube. 15.33 (a) Zero net charge on each surface of the sphere. (b) The negative charge lowered into the sphere repels − 5 µ C to the outside surface, and leaves + 5 µ C on the inside surface of the sphere. (c) The negative charge lowered inside the sphere neutralizes the inner surface, leaving zero charge on the inside . This leaves − 5µ C on the outside surface of the sphere. (d) When the object is removed, the sphere is left with − 5.00 µ C on the outside surface and zero charge on the inside . 15.34 (a) The dome is a closed conducting surface. Therefore, the electric field is zero everywhere inside it. At the surface and outside of this spherically symmetric charge distribution, the field is as if all the charge were concentrated at the center of the sphere. (b) At the surface, E= 9 2 2 −4 k e q ( 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C )( 2.0 × 10 C ) = = 1.8 × 10 6 N C 2 R2 ( 1.0 m ) Electric Forces and Electric Fields (c) Outside the spherical dome, E = ( 8.99 × 10 E= 15.35 9 ke q . Thus, at r = 4.0 m , r2 N ⋅ m 2 C2 )( 2.0 × 10 −4 C ) ( 4.0 m ) 21 2 = 1.1 × 10 5 N C For a uniformly charged sphere, the field is strongest at the surface. Thus, Emax = k e qmax , R2 6 R2 Emax ( 2.0 m ) ( 3.0 × 10 N C ) = = = 1.3 × 10 −3 C ke 8.99 × 109 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 2 qmax or 15.36 If the weight of the drop is balanced by the electric force, then mg = q E = eE or the mass of the drop must be m= −19 4 eE ( 1.6 × 10 C )( 3 × 10 N C ) = ≈ 5 × 10 −16 kg 2 g 9.8 m s 3m 4 But, m = ρV = ρ π r 3 and the radius of the drop is r = 3 4πρ 3 ( 5 × 10 −16 kg ) r= 3 4π ( 858 kg m ) 15.37 (a) 13 = 5.2 × 10 −7 m or r~ 1 µ m F = qE = ( 1.60 × 10 −19 C )( 3.0 × 10 4 N C ) = 4.8 × 10 −15 N (b) a = 15.38 13 F 4.8 × 10 −15 N = = 2.9 × 1012 m s 2 −27 mp 1.673 × 10 kg The flux through an area is Φ E = EA cosθ , where θ is the angle between the direction of the field E and the line perpendicular to the area A. (a) Φ E = EA cosθ = ( 6.2 × 10 5 N C )( 3.2 m 2 ) cos 0° = 2.0 × 106 N ⋅ m 2 C (b) In this case, θ = 90° and Φ E = 0 22 15.39 CHAPTER 15 The area of the rectangular plane is A = ( 0.350 m )( 0.700 m ) = 0.245 m 2 . (a) When the plane is parallel to the yz plane, θ = 0° , and the flux is Φ E = EA cosθ = ( 3.50 × 10 3 N C )( 0.245 m 2 ) cos 0° = 858 N ⋅ m 2 C (b) When the plane is parallel to the x-axis, θ = 90° and Φ E = 0 (c) 15.40 Φ E = EA cosθ = ( 3.50 × 10 3 N C )( 0.245 m 2 ) cos 40.0° = 657 N ⋅ m 2 C In this problem, we consider part (b) first. (b) Since the field is radial everywhere, the charge distribution generating it must be spherically symmetric . Also, since the field is radially inward, the net charge inside the sphere is negative charge . keQ . Thus, just r2 outside the surface where r = R , the magnitude of the field is E = k e Q R2 , so (a) Outside a spherically symmetric charge distribution, the field is E = R2 E ( 0.750 m ) ( 890 N C ) Q= = = 5.57 × 10 −8 C = 55.7 nC 9 2 2 ke 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C 2 Since we have determined that Q < 0 , we now have Q = − 55.7 nC 15.41 Φ E = EA cosθ and Φ E = Φ E , max when θ = 0° Thus, E = 15.42 Φ E , max A = Φ E , max πd 4 2 = 4 ( 5.2 × 10 5 N ⋅ m 2 C ) π ( 0.40 m ) 2 = 4.1 × 106 N C k q Φ E = EA cosθ = e 2 ( 4π R2 ) cos 0° = 4π k e q R Φ E = 4π ( 8.99 × 10 9 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 )( 5.00 × 10 −6 C ) = 5.65 × 10 5 N ⋅ m 2 C Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.43 23 We choose a spherical gaussian surface, concentric with the charged spherical shell and of radius r. Then, ΣEA cosθ = E ( 4π r 2 ) cos 0° = 4π r 2 E . (a) For r > a (that is, outside the shell), the total charge enclosed by the gaussian surface is Q = + q − q = 0 . Thus, Gauss’s law gives 4π r 2 E = 0, or E = 0 . (b) Inside the shell, r < a , and the enclosed charge is Q = + q . Therefore, from Gauss’s law, 4π r 2 E = q q kq , or E = = e2 2 r 4π ∈0 r ∈0 G kq The field for r < a is E = e2 directed radially outward . r 15.44 Construct a gaussian surface just barely inside the surface of the conductor, where E = 0 . Q = 0 inside. Thus, any excess charge residing on Since E = 0 inside, Gauss’ law says ∈0 the conductor must be outside our gaussian surface (that is, on the surface of the conductor). 15.45 E = 0 at all points inside the conductor, and cosθ = cos 90° = 0 on the cylindrical surface. Thus, the only flux through the gaussian surface is on the outside end cap and Gauss’s Q . law reduces to ΣEA cosθ = EAcap = ∈o The charge enclosed by the gaussian surface is Q = σ A , where A is the cross-sectional area of the cylinder and also the area of the end cap, so Gauss’s law becomes EA = 15.46 σA ∈o , or E = σ ∈o Choose a very small cylindrical gaussian surface with one end inside the conductor. Position the other end parallel to and just outside the surface of the conductor. Since, in static conditions, E = 0 at all points inside a conductor, there is no flux through the inside end cap of the gaussian surface. At all points outside, but very close to, a conductor the electric field is perpendicular to the conducting surface. Thus, it is parallel to the cylindrical side of the gaussian surface and no flux passes through this cylindrical side. The total flux through the gaussian surface is then Φ = EA , where A is the crosssectional area of the cylinder as well as the area of the end cap. 24 CHAPTER 15 The total charge enclosed by the cylindrical gaussian surface is Q = σ A , where σ is the charge density on the conducting surface. Hence, Gauss’s law gives EA = 15.47 F= 15.48 (a) k e q1 q2 r2 F= σA or E = ∈0 σ ∈o 9 2 −19 k e 2 ( 8.99 × 10 N ⋅ m C )( 1.60 × 10 C ) = e2 = = 57.5 N 2 r ( 2.00 × 10-15 m ) 2 k e q1 q2 r2 = ( 8.99 × 10 = 9 ke e 2 r2 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 )( 1.60 × 10 −19 C ) ( 0.53 × 10 −10 m) 2 = 8.2 × 10 −8 N 2 (b) F = me ac = me ( v 2 r ) , so r⋅F = v= me 15.49 ( 0.53 × 10 m )( 8.2 × 10 −8 N ) −10 9.11 × 10 -31 kg The three contributions to the resultant electric field at the point of interest are shown in the sketch at the right. = 2.2 × 10 6 m s y 4.0 nC 5.0 nC The magnitude of the resultant field is ER = −E1 + E2 + E3 ER = − k e q1 r12 + k e q2 r22 + k e q3 N ⋅ m2 ER = 8.99 × 109 C2 r32 ur E1 3.0 nC r3 = 1.2 m r2 = 2.0 m r1 = 2.5 m q1 q2 q3 = ke − 2 + 2 + 2 r2 r3 r1 4.0 × 10 −9 C 5.0 × 10 −9 C 3.0 × 10 −9 C + + − 2 2 2 ( 1.2 m ) ( 2.5 m ) ( 2.0 m ) G ER = + 24 N C , or E R = 24 N C in the +x direction ur E2 ur E3 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.50 ur y T q Consider the free-body diagram shown at the right. ΣFy = 0 ⇒ T cosθ = mg or T = mg cosθ ur Fe ΣFx = 0 ⇒ Fe = T sin θ = mg tan θ qE = mg tan θ , or q = 15.51 ( 2.00 × 10 −3 mg tan θ E kg )( 9.80 m s 2 ) tan 15.0° 1.00 × 10 N C 3 = 5.25 × 10 −6 C = 5.25 µ C (a) At a point on the x-axis, the contributions by the two charges to the resultant field have equal magnitudes kq given by E 1 = E2 = e2 . r The components of the resultant field are k q k q Ey = E1 y − E2 y = e2 sin θ − e2 sin θ = 0 r r Since y q r a a q b q k e ( 2q ) k q k q Ex = E1x + E2 x = e2 cosθ + e2 cosθ = cosθ 2 r r r and cosθ b r b b = 2 = 3 = , the resultant field is 32 2 r r r ( a2 + b 2 ) G ER = k e ( 2q ) b (a 2 + b2 ) 32 x ur mg Since Fe = qE , we have q= 25 in the +x direction r ur E1 q q ur E2 x 26 CHAPTER 15 (b) Note that the result of part (a) may be written as ER = ke (Q ) b (a 2 + b2 ) 32 where Q = 2q is the total charge in the charge distribution generating the field. In the case of a uniformly charged circular ring, consider the ring to consist of a very large number of pairs of charges uniformly spaced around the ring. Each pair consists of two identical charges located diametrically opposite each other on the ring. The total charge of pair number i is Qi . At a point on the axis of the ring, this pair of charges generates an electric field contribution that is parallel to the axis and ke bQi . has magnitude Ei = 32 ( a2 + b2 ) The resultant electric field of the ring is the summation of the contributions by all pairs of charges, or ke b ΣQi = ke bQ 3 2 ER = ΣEi = 32 2 2 (a + b ) ( a2 + b 2 ) where Q = ΣQi is the total charge on the ring. G ER = 15.52 (a) ay = (a keQ b 2 vy2 − v02 y 2 ( ∆y ) + b2 ) 32 ( 21.0 = in the +x direction m s) − 0 2 2 ( 5.00 m ) = 44.1 m s 2 ( downward ) Since ay > g , the electrical force must be directed downward, aiding the gravitational force in accelerating the bead. Because the bead is positively charged, the electrical force acting on it is in the direction of the electric field. Thus, the field is directed downward . (b) Taking downward as positive, ΣFy = qE + mg = may . Therefore, q= ( m ay − g ) E (1.00 × 10 = kg ) ( 44.1 − 9.80 ) m s 2 = 3.43 × 10 −6 C = 3.43 µ C 1.00 × 10 4 N C −3 Electric Forces and Electric Fields 15.53 +8.00 mC Because of the spherical symmetry of the charge distribution, any electric field present will be radial in direction. If a field does exist at distance R from the center, it is the same as if the net charge located within r ≤ R were concentrated as a point charge at the center of the inner sphere. Charge located at r > R does not contribute to the field at r = R . 2.00 cm 5.00 cm 4.00 cm (a) At r = 1.00 cm , E = 0 since static 4.00 mC electric fields cannot exist within conducting materials. (b) The net charge located at r ≤ 3.00 cm is Q = +8.00 µ C . Thus, at r = 3.00 cm , E= keQ r2 ( 8.99 × 10 = 9 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 ) ( 8.00 × 10 −6 C ) ( 3.00 × 10 −2 m) 2 = 7.99 × 107 N C ( outward ) (c) At r = 4.50 cm , E = 0 since this is located within conducting materials. (d) The net charge located at r ≤ 7.00 cm is Q = + 4.00 µ C . Thus, at r = 7.00 cm , E= = keQ r2 ( 8.99 × 10 9 N ⋅ m 2 C2 ) ( 4.00 × 10 −6 C ) ( 7.00 × 10 −2 m) 2 27 = 7.34 × 10 6 N C ( outward ) 28 15.54 CHAPTER 15 The charges on the spheres will be equal in magnitude and opposite in sign. From F = k e q2 r 2 , this charge must be q= F ⋅ r2 = ke (1.00 × 10 4 N ) ( 1.00 m ) 8.99 × 109 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 2 = 1.05 × 10 −3 C The number of electrons transferred is n= q 1.05 × 10 −3 C = = 6.59 × 1015 e 1.60 × 10 −19 C The total number of electrons in 100-g of silver is electrons 23 atoms 1 mole 25 N = 47 ( 100 g ) = 2.62 × 10 6.02 × 10 atom mole 107.87 g Thus, the fraction transferred is n 6.59 × 1015 = = 2.51 × 10 −10 (that is, 2.51 out of every 10 billion). 25 N 2.62 × 10 15.55 Φ E = EA cosθ = ( 2.00 × 10 4 N C ) ( 6.00 m )( 3.00 m ) cos10.0° = 3.55 × 10 5 N ⋅ m 2 C 15.56 (a) The downward electrical force acting on the ball is Fe = qE = ( 2.00 × 10 −6 C )( 1.00 × 10 5 N C ) = 0.200 N The total downward force acting on the ball is then F = Fe + mg = 0.200 N+ ( 1.00 × 10 -3 kg )( 9.80 m s 2 ) = 0.210 N Thus, the ball will behave as if it was in a modified gravitational field where the effective free-fall acceleration is “ g” = F 0.210 N = = 210 m s 2 -3 m 1.00 × 10 kg Electric Forces and Electric Fields 29 The period of the pendulum will be T = 2π (b) L 0.500 m = 2π = 0.307 s " g" 210 m s 2 Yes . The force of gravity is a significant portion of the total downward force acting on the ball. Without gravity, the effective acceleration would be “ g” = Fe 0.200 N = = 200 m s 2 m 1.00 × 10 -3 kg 0.500 m = 0.314 s 200 m s 2 giving T = 2π a 2.28% difference from the correct value with gravity included. 15.57 The sketch at the right gives a free-body diagram of the positively charged sphere. Here, F1 = k e q 2 10° ur T 2 r is the attractive force exerted by the negatively charged sphere and F2 = qE is exerted by the electric field. ΣFy = 0 ⇒ T cos10° = mg or T = ur F1 mg cos10° ΣFx = 0 ⇒ F2 = F1 +T sin10° or qE = ke q r2 y ur F2 ur mg 2 + mg tan10° At equilibrium, the distance between the two spheres is r = 2 ( L sin10° ) . Thus, E= = ke q 4 ( L sin10° ) ( 8.99 × 10 9 2 + mg tan10° q N ⋅ m 2 C2 )( 5.0 × 10 −8 C ) 4 ( 0.100 m ) sin10° or the needed electric field strength is 2 + ( 2.0 × 10 −3 kg )( 9.80 m s 2 ) tan10° ( 5.0 × 10 E = 4.4 × 10 5 N C −8 C) x 30 15.58 CHAPTER 15 y As shown in the sketch, the electric field at any point on the x-axis consists of two parts, one due to each of the charges in the dipole. r +q q E = E+ − E− = E= ke q ( x − a) 2 − ke q r+2 − a ur E a r+ ke q ( x + a) x r−2 ke q 2 ur E+ ( x + a )2 − ( x − a )2 4 ax = ke q = k q e 2 2 ( x 2 − a 2 )2 ( x − a ) ( x + a ) 4 k e qa 4 ax Thus, if x 2 >> a 2 , this gives E ≈ k e q 4 = x3 x 15.59 y (a) Consider the free-body diagram for the ball given in the sketch. ΣFx = 0 ⇒ T sin 37.0° = qEx or T = qEx sin 37.0° and ΣFy = 0 ⇒ qEy + T cos 37.0° = mg or qEy + qEx cot 37.0° = mg ur 37.0° T ur qEy ur mg ur qEx x 1.00 × 10 −3 kg )( 9.80 m s 2 ) ( mg Thus, q = = Ey + Ex cot 37.0° 5.00 + ( 3.00 ) cot 37.0° × 10 5 N C = 1.09 × 10 −8 C = 10.9 nC (b) From ΣFx = 0 , we found that T = Hence, 15.60 (1.09 × 10 T= −8 qEx . sin 37.0° C )( 3.00 × 10 5 N C ) sin 37.0° = 5.44 × 10 −3 N (a) At any point on the x-axis in the range 0 < x < 1.00 m , the contributions made to the resultant electric field by the two charges are both in the positive x direction. Thus, it is not possible for these contributions to cancel each other and yield a zero field. Electric Forces and Electric Fields 31 (b) Any point on the x-axis in the range x < 0 is located closer to the larger magnitude charge ( q = 5.00 µ C ) than the smaller magnitude charge ( q = 4.00 µ C ) . Thus, the contribution to the resultant electric field by the larger charge will always have a greater magnitude than the contribution made by the smaller charge. It is not possible for these contributions to cancel to give a zero resultant field. (c) If a point is on the x-axis in the region x > 1.00 m , the contributions made by the two charges are in opposite directions. Also, a point in this region is closer to the smaller magnitude charge than it is to the larger charge. Thus, there is a location in this region where the contributions of these charges to the total field will have equal magnitudes and cancel each other. (d) When the contributions by the two charges cancel each other, their magnitudes must be equal. That is, ke ( 5.00 µ C ) x 2 = ke ( 4.00 µ C ) 4 or x − 1.00 m = + x 2 5 ( x − 1.00 m ) Thus, the resultant field is zero at 15.61 x= 1.00 m = + 9.47 m 1− 4 5 We assume that the two spheres have equal charges, so the repulsive force that one exerts on the other has magnitude Fe = k e q2 r 2 . ur T 10° ur Fe From Figure P15.61 in the textbook, observe that the distance separating the two spheres is r = 3.0 cm + 2 ( 5.0 cm ) sin10° = 4.7 cm = 0.047 m From the free-body diagram of one sphere given above, observe that ΣFy = 0 ⇒ T cos10° = mg or T = mg cos10° and mg ΣFx = 0 ⇒ Fe = T sin10° = sin10° = mg tan10° cos10° ur mg 32 CHAPTER 15 Thus, k e q2 r 2 = mg tan10° ( 0.015 kg ) ( 9.8 mgr 2 tan10° = q= ke or m s 2 ) ( 0.047 m ) tan10° 2 8.99 × 109 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 giving q = 8.0 × 10 −8 C or q ~ 10 −7 C 15.62 Consider the free-body diagram of the rightmost charge given below. ΣFy = 0 ⇒ T cosθ = mg ur T T = mg cosθ or and ΣFx = 0 ⇒ Fe =T sin θ = ( mg cosθ ) sin θ = mg tan θ But, Fe = Thus, 5k e q 2 = mg tan θ or q = 4 L2 sin 2 θ q ur Fe ur mg ke q2 ke q2 ke q2 ke q2 5k e q 2 + = + = 2 2 r12 r22 ( L sin θ ) ( 2L sin θ ) 4L2 sin 2 θ 4 L2 mg sin 2 θ tan θ 5k e If θ = 45°, m = 0.10 kg, and L = 0.300 m then 4 ( 0.300 m ) ( 0.10 kg ) ( 9.80 m s 2 ) sin 2 ( 45° ) tan ( 45° ) 2 q= or 15.63 5 ( 8.99 × 10 9 N ⋅ m 2 C 2 ) q = 2.0 × 10 −6 C = 2.0 µ C (a) When an electron (negative charge) moves distance ∆x in the direction of an electric field, the work done on it is W = Fe ( ∆x ) cosθ = eE ( ∆x ) cos180° = − eE ( ∆x ) ( ) From the work-energy theorem Wnet = KE f − KEi with KE f = 0 , we have − eE ( ∆x ) = − KEi , or E = KEi 1.60 × 10 −17 J = = 1.00 × 10 3 N C e ( ∆x ) ( 1.60 × 10 −19 C ) ( 0.100 m ) 33 Electric Forces and Electric Fields (b) The magnitude of the retarding force acting on the electron is Fe = eE , and Newton’s second law gives the acceleration as a = − Fe m = − eE m . Thus, the time required to bring the electron to rest is t= 2m ( KEi ) v − v0 0 − 2 ( KEi ) m = = − eE m a eE or t= 2 ( 9.11 × 10 −31 kg )( 1.60 × 10 −17 J ) (1.60 × 10 −19 C )( 1.00 × 10 N C ) 3 = 3.37 × 10 −8 s = 33.7 ns (c) After bringing the electron to rest, the electric force continues to act on it causing the electron to accelerate in the direction opposite to the field at a rate of a= 15.64 −19 3 eE ( 1.60 × 10 C )( 1.00 × 10 N C ) = = 1.76 × 1014 m s 2 9.11 × 10 -31 kg m (a) The acceleration of the protons is downward (in the direction of the field) and −19 Fe eE ( 1.60 × 10 C ) ( 720 N C ) = = 6.90 × 1010 m s 2 ay = = 1.67 × 10 −27 kg m m The time of flight for the proton is twice the time required to reach the peak of the arc, or v 0y t = 2tpeak = 2 ay 2v sin θ = 0 ay ur v0 The horizontal distance traveled in this time is 2v sin θ R = v0 x t = ( v0 cosθ ) 0 ay v 2 sin 2θ = 0 ay ur a q R 34 CHAPTER 15 Thus, if R = 1.27 × 10 −3 m , we must have sin 2θ = ay R v02 = ( 6.90 × 10 10 m s 2 )( 1.27 × 10 −3 m ) ( 9 550 m s) 2 = 0.961 giving 2θ = 73.9° or 2θ = 180° − 73.9° = 106.1° . Hence, θ = 37.0° or 53.0° (b) The time of flight for each possible angle of projection is: For θ = 37.0° : t= For θ = 53.0° : t= 2v0 sin θ ay 2v0 sin θ ay = = 2 ( 9 550 m s ) sin 37.0° 6.90 × 1010 m s 2 2 ( 9 550 m s ) sin 53.0° 6.90 × 10 10 m s 2 = 1.66 × 10 −7 s = 2.21 × 10 −7 s