Spring 2010

REACHOUT NEWS

School of Social Work

Stephen F. Austin

State University

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

Inside this issue:

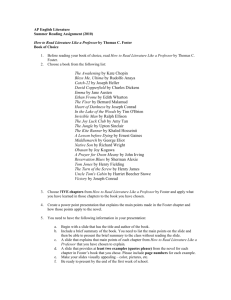

RAD: How is a Parent to Parent? RAD: HOW IS A PARENT TO PARENT?

1‐7 Wilma Cordova, LCSW Introduction

Regional News 8‐9 Child Welfare Information Center 10 Earn One Hour Credit 11‐

12 Foster Parent Conference 13 CWPDP Staff 13 The author has 12 years clinical experience while in private practice in New Mexico, working with chil‐

dren who have been abused and neglected She is currently an assistant professor in the School of So‐

cial Work at Stephen F. Austin State University and has taught primarily in the Bachelor Social Work Program for approximately 10 years. While the case studies in the article are based on real cases, names and some of the circumstances have been changed to protect identities. The following is an excerpt from the entire article posted at http://www2.sfasu.edu/aas/socwk/CWPDP/

cwpdpoverview.html. Case study: Lisa, age 12, is a petite blue‐

eyed and blonde‐haired pre‐adolescent who was placed in her sixth foster home three years ago, after being removed from her bio‐

logical mother’s care at age 4. She appeared much younger than her chronological age. Lisa and her 10‐year‐old‐sister, Amy, are being considered for adoption by the Norton family. Recently Lisa was referred for coun‐

seling by Child Protective Services after she fell from the stair banister in the home the From the Director…..Becky Price-Mayo, MSW, LBSW-IPR

REACHOUT NEWS

Published by

Child Welfare Professional

Development Project

School of Social Work

Stephen F. Austin

State University

P. O. Box 6165, SFA Station

Nacogdoches, Texas 75962

Tel: (936) 468-1846

Fax: (936) 468-7699

E-mail: bmayo@sfasu.edu

Funding is provided by contract

with the Texas Department of

Family and Protective Services.

All rights reserved. This newsletter

may not be reproduced in whole or

in part without written permission

from the publisher. The contents of

this publication are solely the

responsibility of the Child Welfare

Professional Development Project

and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the funders.

Spring is just around the corner, and we are busy gearing up for the 13th An‐

nual Region 5 Foster & Adoptive Training Conference and Youth Leadership Conference! Both conferences will be held Saturday, April 17th. Along with foster parent associations and CPS staff, there are SFA Social Work interns and graduate assistants, as well as many student volunteers that will be helping to plan, organize and assist with the conferences. Region 5 foster parents will soon have an opportunity to nominate ʺFoster Parent of the Yearʺ and ʺCPS Staff Person of the Yearʺ with the awards being presented at the conference luncheon. In addition, the conference planning committee decided against having a keynote speaker this year and have up to 16 workshops planned for the foster parent conference. This is a tremendous profes‐

sional development opportunity for East Texas. Watch for registration information in early March. We look forward to seeing you there! We are very excited to feature an article by Wilma Cordova, SFA assistant professor in the School of Social Work, in this issue of the REACHOUT Newsletter. She has a wealth of experience working with children in care and is currently a CASA volunteer. Specific strategies for parenting children with Reactive Attachment Disorder are provided in the article, and the enclosed learning activity and evaluation may be completed and re‐

turned to your case worker for ONE HOUR of foster parent training! (Continued on page 13)

Page 2

REACHOUT NEWS

INTRODUCTION

family is having built. However, after several stories from Lisa, no one could quite figure out how the incident occurred. The home, not yet complete, continues to be under construc‐

tion but is functional enough downstairs for the family to utilize. The family had recently moved their three foster chil‐

dren into the home where they had sufficient privacy and ne‐

cessities. Lisa is quite charming and very verbal. She indi‐

cated that she told lies about the fall so as not to get into trou‐

ble because she had been told several times not to play on the banister. The family indicates this is a common pattern but that Lisa has become more con‐

trolling and influential over the younger children, and they fear someone will be seriously in‐

jured. The other foster homes were disrupted due to Lisa’s be‐

havior and what the social worker termed “inability to han‐

dle Lisa’s storytelling and inap‐

propriate relationships.” The Norton family is reconsidering the adoption, although they indi‐

cate they will adopt Amy as she does not seem to exhibit the same behaviors. They verbalize that Lisa’s behavior is more than they can handle and has become worse over the last two years, with problems now being reported from school. The problems at school entail poor academic performance and diffi‐

culty with peers. She refuses to go to school whenever there is some type of competition by faking illness. They have agreed to seek counseling services and are willing to participate to any extent possible in order to continue to provide a family for Lisa. Normal emotional/social developmental milestones for 10‐12 years old: ability to interact with peers; ability to engage in competition; developing and testing values and beliefs that will guide present and future behaviors; a strong sense of group identity and defines self through peers; acquiring a sense of accomplishment based upon the achievement of greater strength and self‐control; and defines self‐concept in part by success in school (National Resource Center for Family‐Centered Practice and Permanency Planning, 2009). Lisa’s emotional and developmental gaps are in the ar‐

eas of peer relationships (confliction and lack of), lack of interest in competition and lack of interest in success at school. Many foster parents and adoptive parents are well aware of the challenges encountered with children who have suffered from abuse and neglect. Obtaining a fac‐

tual diagnosis can certainly alleviate much heartache as to how treatment and parenting is to follow after obtain‐

ing custody of a child with Reactive Attachment Disor‐

der (RAD). RAD is one of the most difficult disorders to pinpoint and is often con‐

fused with Post Traumatic Disorder, Pervasive Disorders (autism) and Depressive Dis‐

orders. Symptoms include developmental delays, de‐

pression, hyperactivity, anxi‐

ety and other symptoms very similar to other disorders. Some of these symptoms can be treated with medications. Medications will help alle‐

viate the symptoms, but the disorder will continue to be manifested in behavior. Following up with the appro‐

priate treatments are imperative, as well as assuring a safe and nurturing environment for those children suf‐

fering from RAD. One cannot express how important a safe and nurturing environment is for these children. It is the reason they are inflicted with the disorder in the first place. What is RAD?

Simply stated, it is a disorder characterized by a child’s inability to have relationships. We all have heard the statement “no man is an island.” Have we ever really thought about the impact of those who had no one at the very beginning of life? If this statement is true and no one responded to the cry of an infant who needed changing, feeding, medical care or simply a cuddle, what impact will this have on one’s ability to relate to individuals? Infants who live this situation probably learn that no matter how long or hard they cry, no one is coming. This experience is embedded deep into the Page 3

REACHOUT NEWS

WHAT IS RAD?

child’s brain to the point of actually affecting brain de‐

velopment and creating the inability to develop at a nor‐

mal rate or in a manner conducive for relating in an ap‐

propriate manner. The development of the brain in‐

volves a complex process that is difficult to understand and even more difficult to accept because of the grave importance of the caretaker’s role in its development. Simply stated, RAD is the lack of the development of the brain, particularly the part of the brain that develops relationships. Imagine the inner workings of a computer and all the wirings, batteries and transmitters that have to work systematically to make the computer function. The same is true for a brain, except that we are working with neuro‐chemicals and nerve connectivity. It is a good thing there are doctors that specialize in neurology and understand the brain and its development. According to Corbin (2007), early childhood traumas affect the structure of the brain and all the physiological processes. It is important to get a thorough history, since the diagnosis of RAD depends on a history of ne‐

glect. What parents, school personnel and other caretak‐

ers see are the behaviors caused by this disorder. Par‐

ents especially should be aware of the behaviors associ‐

ated with RAD. The following is a list of some of those behaviors: •

A compulsive need to control others, includ‐

ing caregivers, teachers and other children •

Intense lying, even when “caught in the act” •

Poor response to discipline; aggressive or oppositional‐defiant •

Lack of comfort with eye contact (except when lying) •

Physical contact (too much or too little) •

Interactions lack mutual spontaneity and enjoyment •

Body functioning disturbances (eating, sleeping, urinating, defecating) •

Increased attachment produces discomfort and resistance CONTINUED •

Indiscriminately friendly and charming; eas‐

ily replaced relationships •

Poor communication; many nonsense ques‐

tions and chatter •

Difficulty learning cause/effect, poor plan‐

ning and/or problem solving •

Lack of empathy, little evidence of guilt and remorse for others •

Ability to see only the extremes (all good or all bad) •

Habitual dissociation or hypervigilence •

Pervasive shame, with extreme difficulty re‐

establishing a bond following conflict ( from Rebuilding Attachments with Traumatized Children by Richard Kagan, PhD, 2004, pp 18) Other behaviors include destruction, stealing, lying, bul‐

lying, and cruelty to animals and people (Schwartz & Davis, 2006). In adolescence you will see them mani‐

fested by lack of impulse control, poor self‐regulation, hyperactivity and low frustration tolerance. The main manifestation of the disorder is the inability to form at‐

tachments with individuals. This inability causes diffi‐

culty in functioning within a family unit and other sys‐

tems. The clinical diagnostic manual for psychiatric disorders, known as the DSM‐IV (1994), divides the disorder of reactive attachment into two subtypes: 1.) inhibited type: refers to relationships that are very detached. In this category relationships are not initiated, and there is no reciprocal interaction; 2.) disinhibited type: refers to relationships that are very superficial and nonselective. These children will attach to everyone and discard rela‐

tionships quite easily. Both subtypes are marked by im‐

maturity and inappropriate interactions. To have the disorder, children must have been abused or neglected at a very early age, and some may have experienced fac‐

tors contributing to the disorder while in utero (fetus), Page 4

REACHOUT NEWS

WHAT’S A PARENT TO DO?

particularly if the biological mother was abusing alcohol or other substances. One indicator for developing RAD may be an infant born premature, although these cases continue to be studied. Infants born prematurely may experience disruption of the normal development of the brain and, as a result may develop RAD due to their inability to respond to the caretaker, thus putting them at high risk for neglect (Kemph & Voeller, 2007). More and more researchers and those who study RAD are finding that healthy brain development is essential for establishing healthy attachments. To establish healthy attachments, stimulation and nurturance from another individual is vital in developing the brain’s capacity to trust others and begin to learn about relationships. Parents who foster or adopt children diagnosed with RAD have a challenge in obtaining the correct diagnosis for the best treatment possible and nurturing a child to optimal emotional health. What’s a Parent to Do?

Normal emotional and social development for 0‐18 months: wanting to have needs met; a socializing sense of security; smiling spontaneously and responsively; movement; laughing aloud; knowing mother or primary caregiver; responding to tickling; preferring primary caregiver; and crying when strangers approach. Normal emotional and social development for 18‐36 months: awareness of limits and says “no”; establishing a positive sense of self and exploring environment; de‐

veloping communication skills and experiencing re‐

sponsiveness of others; doing things for self; and mak‐

ing choices (Natural Resource Center for Family‐

Centered Practice and Permanency Planning, 2009) Case study: Cody is a 2 year‐old toddler attending day care. He is currently in foster care with the Hernandez family and has been under their care for one year. Upon arrival of the foster mother at the end of the workday, the substitute atten‐

dant noticed that Cody did not seem excited or happy to see her. As a matter of fact, the attendant had to encourage him and eventually carried Cody to her with much animation about his mother’s arrival. When Cody did not respond with glee or even an ounce of recognition, the attendant refused to release Cody in her care thinking Mrs. Hernandez was a stranger trying to abduct him. Following the director’s inter‐

vention and assurance that Cody did belong in Mrs. Hernan‐

dez’s care, the attendant felt comfortable releasing Cody. The attendant remained confused as to why Cody did not express joy or happiness at his foster parent’s arrival. While she re‐

mained puzzled, she did began to reflect on some of his other odd behaviors, including the fact that he rarely played with others, did not speak or initiate any type of activity (i.e. self‐

feeding, dressing or toileting) and required much encourage‐

ment to explore and interact. She discovered that Cody was in his second foster home after his mother tested positive for sub‐

stance abuse following a report of neglect. This case points the gaps in the emotional and social development for a child of Cody’s age in many of the milestones. He does not differentiate between the atten‐

dant and the caretaker, does not verbalize, shows no emotion and does not play or initiate any activity or in‐

teraction. The mother’s substance abuse and neglect is most likely the cause of Cody’s disorder. Professional Treatment: Parents should have someone they can speak to about the child’s behavior and seek out professional advice should they suspect the exis‐

tence of RAD. Many of those working with children in foster and adoptive placements should be familiar with RAD. If not, you as the primary caretaker can begin the education process. The parent will know their children better than anyone else, so it is important to journal pat‐

terns of behaviors that are concerning. Working with a child neurologist is ideal, but the child’s physician should be able to make any appropriate referrals for Page 5

REACHOUT NEWS

HOW IS A PARENT TO PARENT?

medications if they are uncomfortable doing so them‐

selves. Medications can help address and alleviate some of those concerning behaviors. Most likely a physician will prescribe medications in the category of SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Case study: Lisa’s school problems continued, and she was required to repeat the sixth grade due to failing grades. She was unable to comprehend concepts and fell behind in the ma‐

terial because of her many absences. Her teachers reported that she was very aggressive with peers and had several physi‐

cal altercations, which had not yet resulted in serious injury. The foster parents were also concerned with her aggressive behavior at home and her lack of desire to attend school. They are hoping for a better school year and willing to speak with the physician. In this case Lisa’s pediatrician referred Lisa to a psychia‐

trist who prescribed Seroquel and Adderall. Within the first three months of school Lisa was able to concentrate and focus, which greatly improved her grades but also seemed to lessen the aggression and severe mood swings. School became a more positive experience and Lisa’s attendance at school was excellent. cial in helping children with RAD in their growth to be‐

come productive and emotionally healthy adults. The reward will be exhilarating but delayed, as children ex‐

periencing RAD do not offer much in the form of grati‐

tude and appreciation. Remember, their lives started off horrifically and their existence never acknowledged. Parenting is a learning process, and it is up to the parent to set limits, remain calm and become flexible. Sounds simple, but as all parents know, parenting is tough! FOR MORE IN-DEPTH DISCUSSION

on the causes of RAD and information on professional treatment, such as Dyadic Development Psychotherapy, Theraplay, and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, as well

as alternative therapies, including animalassisted therapy, therapeutic and play therapy,

please access the author’s complete article at

http://www2.sfasu.edu/aas/socwk/CWPDP/

cwpdpoverview.html.

How is a Parent to Parent?

Parents of children with RAD must learn as much as they can about the disorder. Most importantly, be cer‐

tain that your child has this specific disorder. Those who suspect this disorder should have it diagnosed by a professional. Consistent and nurturing parenting is cru‐

Levy and Orlans (1998) outline some basic parenting concepts (for a complete list of these basic concepts, re‐

view their book titled, Attachment, Trauma, and Healing Understanding and Treating Attachment Disorder in Chil‐

dren and Families). One concept is awareness of your own family of origin and how parenting occurred. We parent the way we were parented unless we change what we learned. We realize we don’t want to be like our parent(s) and attempt to parent differently. Remem‐

ber that as a parent, we must serve as a role model when communicating, coping, problem‐solving and managing emotions. Be open to learning new techniques and par‐

ticipating in treatments. What works for “normal” chil‐

dren does not work for children experiencing RAD. Teach the child to attach by providing much structure and nurturance. Adjust structure as the child matures. It is up to the parent to teach the child responsibility, re‐

spectfulness, resourcefulness and about being reciprocal Page 6

REACHOUT NEWS

HOW IS A PARENT TO PARENT?

in relationships. Other concepts include the importance of having support from family members and commu‐

nity. Understand that hope should be conveyed from all systems working with the child and that hope is con‐

veyed in all aspects of the child’s life. Learning basic objectives for effective parenting should be revisited and applied when living with a child experiencing RAD. Levy and Orlans (1998) have written a book tailored specifically for the parents of children with attachment disorders. They discuss goals and methods that are practical and effective in parenting the unique character‐

istics of children with attachment disorders. Many of them are relevant for children not having attachment disorders, so you may have learned about some of these methods or at least have read about them. One such goal is to create a healing environment that is conducive to solutions. Children with attachment disorders are behaviorally disorganized and need a predictable sense of order. You can do this by keeping to a schedule and routine, setting appropriate rules and limits, setting clear boundaries by not allowing a child to play one adult against another, and holding the child account‐

able. Be sure that they understand the expectations, standards and rules. FOSTER PARENTS!

CWIC has Levy & Orlan’s Attachment,

Trauma, and Healing: Understanding

and Treating Attachment Disorders in

Children and Families available for

checkout!

Learn to communicate effectively. There are many ways to do so. The following are some techniques to commu‐

nicate effectively: start by sending warm, loving and accepting messages; use eye contact and touching; make positive statements; be specific about what behavior you are praising or approving; be emotionally animated when providing positive praise and remain neutral with negative behavior; and learn a resource model of ques‐

tioning that encourages the child to find their own solu‐

tions and avoids power struggles. CONTINUED

Making a child responsible for their actions is an impor‐

tant role of the parent. Parents sometimes take too much responsibility for their child’s irresponsibility. To address this, one must first identify the individual who should be the most responsible (assume it is the child) and have them identify how much responsibility they are taking realistically and compare it to how much oth‐

ers are taking. Have the child then identify how much they should be taking. Parenting creatively is another objective identified by Levy and Orlans (1999). They provide several methods to be creative in parenting the child with attachment disorders. Some include: “hassle time,” which is a method to increase reciprocity by repayment (i.e. for your temper tantrum in the store, you will have an extra chore tonight); “parent on strike” entails the parent dis‐

continuing services, such as a ride to the mall for a child refusing to be responsible; “one‐minute reprimand” al‐

lows the parent to confront the behavior in a loving and concerned manner by direct confrontation (i.e. holding of the shoulders, direct eye contact or a hug). Case study: After attending parenting classes, learning more about creative parenting and observing a play therapist, Mrs. Hernandez, Cody’s foster parent decided, to experiment and engage Cody in play. She spent 20 minutes in a closed, empty room at home with only a few toys on the floor. She played with the toys alone until Cody eventually became curi‐

ous and sat to observe her play. This she did daily until Cody began to attempt to play with her. After several weeks of this, Cody began to play alone and attempt to verbalize while play‐

Page 7

REACHOUT NEWS

CONCLUSION

ing. The day care reported progress with socialization, com‐

munication and autonomy during this time. It appeared that Cody was finally meeting some age‐appropriate developmental milestones. This was due, in part, to the primary caretaker’s efforts to become creative, patient, consistent and proactive. Parenting requires knowledge about developmental stages and the milestones mastered at specific ages. An infant is totally dependent on the caregiver, toddlers learn about autonomy and the caretaker is attuned to balancing opportunities that allow for autonomy and independence for activity. Children learn competencies, provided they feel a sense of attachment, in four major areas: information processing (knowledge), personal and social skills, judgment to make appropriate choices, and the ability to regulate emotions and impulses. Chil‐

dren who have attachment disorders do not master these competencies, so the caretaker must contain them within the boundaries of their capabilities (Levy & Orlans, 1999). This means that the caretaker must be certain the child can handle responsibility and obligation before more power and freedom is assigned. Remember that chronological age does not necessarily warrant a child’s capability. In the case of Lisa, she may express the desire to play a competitive sport on a team at school, but al‐

lowing her to participate competitively would be a sure way to see her fail due to her inability to interact and socialize within her peer group. Instead, allowing her to participate in an activity outside of school that is less competitive or does not require a team effort might pro‐

duce a more successful experience for both Lisa and her foster parents. Conclusion

Reactive Attachment Disorder is a disorder pertaining to the inability to attach and develop healthy relation‐

ships. The cause is usually that of neglect during a cru‐

cial time of the development of the brain. Studies con‐

tinue to be challenging and hopeful in the treatment of RAD. Parents of a child diagnosed with RAD need to have a supportive and knowledgeable team working with them and their child. Parents must provide a safe and nurturing environment that is conducive for devel‐

opment and healing. This can be done by becoming knowledgeable about RAD, learning to adjust parenting skills accordingly and implementing creative tech‐

niques. Children with RAD do require professional treatment and support and understanding from all enti‐

ties involved with the child’s life. Those who choose to parent children with RAD have a great challenge ahead of them but will also experience a great joy when they experience the small successes that required much ef‐

fort. References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statis‐

tical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Publisher. Corbin, J. (2007). Reactive attachment disorder: A biopsycho‐

social disturbance of attachment. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(6), 539‐552. Kagan, R. (2004). Rebuilding attachments with traumatized chil‐

dren. New York: Hawthorn Press. Kemph, J., & Voeller, K. (2007). Reactive attachment disorder in adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry, 30159‐178. Levy, T. M. & Orlans, M. (1998). Attachment, trauma, and heal‐

ing: Understanding and treating attachment disorders in children and families. Washington DC: CWLA Press. National Resource Center for Family‐Centered Practice and Permanency Planning, (2009). Hunter College School of Social Work, New York: NRCFCPPP. Schwartz, E., & Davis, A. (2006). Reactive attachment disorder: Implications for school readiness and school func‐

tioning. Psychology in the Schools, 43(4), 471‐479. Page 8

REACHOUT NEWS

REGIONAL NEWS

Hello Region 5 Foster Parents,

There is so much going on in our area, and I wanted to share some of this with you in this newsletter. We have exciting news that we will be hiring a new supervisor in Beaumont and getting a new FAD worker in the mid‐

region area. We are really excited about these new addi‐

tions, and we believe that spreading out the work a little more will help our staff to spend more time with the foster parents and our supervisors to spend more time developing staff. This will be a benefit to staff, foster parents and, most importantly, children in foster care. I am also going to try to start recognizing newly verified foster and adoptive families in this newsletter. We want each of you to know that you are valued, and we want the rest of our foster families to celebrate with us your commitment to caring for a child in need. In the last quarter (October to December 2009) the following fami‐

lies have been verified in region 5: We also want to tell you about T3: Third Tuesday Train‐

ing. Region 5 will begin to offer training to foster par‐

ents somewhere in the region every third Tuesday of the month. Training will be offered by DFPS Staff and other professionals, depending on the situation. We are hope‐

ful that this will help us to have a more professional and well‐trained pool of foster families and that it will help you keep up your training hours better and spend a lit‐

tle more time networking with and receiving support from other foster families. The current schedule is on the following page. We are really looking forward to seeing all of you at these trainings and hope that you will make it a regular part of your routine. Watch your mail for more infor‐

mation. Another exciting change is the Fostering Connections initiative. Foster Connections is about verifying kinship families to be foster families for the children for whom they are caring. The CVS and Kinship programs are working right now to find kinship placements who have the capability to meet foster parenting standards and want to do so. FAD will be working with the these families to verify them as foster parents so that they will have access to the same benefits and support systems that non‐relative foster parents are accessing. This is an exciting adventure and one that will ensure even more support for children in out of home care. We currently have two families from the Golden Triangle area who are interested, and we hope to have them in our PRIDE class that starts in February. Princelyn and Courtney Abercrombie Daryl and Sharon Thatcher David and Tanya Cowart Larry and Angela Nealy Garry and Desiree Broussard Shirley Thomas Glynnis Craft Gregory and Rebekah Justice Sylvia Johnson Charles and Misty Adams Donnean Surrat Steve and Terry Duval Cheryl Lenard Stacy Green Kevin and Tiffany Daniels Kay Burch and David Saxon Ernest Wayne Robbins Ronnie and Lanell Yates Maria Hebert John and Belinda Rosen Sara Bevills Gwen Jackson Alex and Donna Thomas Alfred and Candy Grantham Johnny and Nancy Simons Kenneth and Patsy Mercer Michael Longmire Ingira Jenkins Richard and Dayra Newton Mark and Dena Standley As you can see, your FAD staff have been VERY busy! We are excited and blessed that each of these families is willing and able to provide a home for a child, either a child they have never known or a relative child in need of long‐term care. Thank you so much to every single foster and adoptive family! You are the backbone of our work, and we appreciate your selfless commitment! Sincerely, Ginny Judson

Region 5 FAD Supervisor

Page 9

REACHOUT NEWS

REGIONAL NEWS

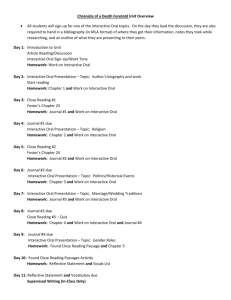

REGION 5 FOSTER PARENT TRAINING SCHEDULE February

16th

Surrogate Parent Training - Judy Morris

Beaumont

20th Floor,

6-8 p.m.

February

16th

Legal Process - Ronnie Cohee

Lufkin

2nd Floor Conference Room

6-8 p.m.

March 16th

Surrogate Parent Training - Judy Morris

Lufkin

2nd Floor Conference Room

6-8 p.m.

March 16th

Legal Process - Ronnie Cohee

Beaumont

20th Floor,

6-8 p.m.

April 13th

Serious Incident Reporting - Ginny Judson and Brandi

LeBlanc

Beaumont

20th Floor,

6-8 p.m.

April 17th

Regional Foster Parent Conference

Nacogdoches

SFA

May 18th

Early Child Brain Dev/SID/Shaken Baby/Infant Care Stella Blakely and Ben Glade

Lufkin

2nd Floor Conference Room

1-3 p.m.

June 15th

Transitioning Children to Adoption - Pat Simms, Depelchin

Beaumont

20th Floor,

6-9 p.m.

July 20th

Drug Training: Recognizing and preventing drug use

in children - Kim West

Beaumont

20th Floor,

6-8 p.m.

July 20th

Hair and Skin Care for Children of Different Racial

Backgrounds - Sonya Holman

Lufkin

2nd Floor Conference Room

6-8 p.m.

August 3rd

Drug Training - Kim West

Lufkin

2nd Floor Conference Room

6-8 p.m.

August

17th

Hair and Skin Care for Children of Different Racial

Backgrounds - Sonya Holman

Port Arthur

Conference

Room

September

21st

Fire Safety (to be set up by Jennifer in the South and

Kathi in the North)

North & South

October

19th

Nutrition (Comm. Agriculture Extension offices)

(to be set up by Ben in the North and Leisa in the

South)

Working with Birth Families (TBA)

North & South

November 16th

December

21st

Lifebooks (TBA)

Page 10

REACHOUT NEWS

Child Welfare Information Center

Fateemah Helaire Graduate Assistant Earn

Foster Parent

Training Credit

Fostering and adopting can be very rewarding; however it is not always easy to manage the difficult challenges of par‐

enting children who have been abused and/or neglected. The Child Welfare Information Center (CWIC) has re‐

sources that will assist foster/adoptive parents in helping children of all ages cope with difficult issues. In the past year and a half, I have worked with foster par‐

ents and provided resources from CWIC. Parents have requested resources about autism, wetting, soiling, youth developing racial and ethnic identity, transracial adoptions, and positive parenting. CWIC has an abundance of re‐

sources that will enhance foster/adoptive parenting skills in many areas. Listed below are just a few of the new re‐

sources CWIC offers to foster/adoptive parents. Foster Parenting is a book that guides the reader through the entire process of foster parenting, from making that first phone call to the arrival of your first foster child. It ex‐

plains how to prepare your home for fostering, the process of caring for a foster child, the adoption process and pro‐

vides resources for coping when a child returns home. House Safety, part of the Foster Parent College DVD Series, is about a social agency professional guiding parents through a 10‐station tour and inspection of a typical foster home. He looks for dangerous conditions that might go unnoticed until seen as a safety hazard to children —

everything from the temperature of hot tap water to unse‐

cured old freezers. Parents assume the role of regulator with self‐scout house inspections, noting deficiencies and making necessary corrections or repairs. Working with Birth Parents I: Visitation, part of the Foster Parent College DVD Series, explains why birth parents vis‐

its are both turbulent and important to your child and how you can assist in making them positive experiences. It suggests ways to clarify your role in the visitation process and who to turn to for support. Using realistic cases, common problems are explored and solved with recommendations for younger and older children. Parenting the Explosive Child is a DVD that helps parents understand the specific cognitive skill deficits that can impair a childʹs capacities for flexibility and frustration tolerance ; step‐by‐step guidance on the approach known as Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) is pro‐

vided for teaching these skills. Live interviews with parents of behaviorally challenging children and an‐

swers to many of the common questions parents have about the CPS approach are also provided. Helping Your Child Overcome an Eating Disorder is a book that guides you as you develop a family plan, which is essential for helping your child overcome his or her problems. You will learn how to communicate effec‐

tively with your child about eating behaviors, access the latest psychological treatments, deal with eating and exercise in the home, and participate in your child’s re‐

covery. Please do not hesitate to call our toll‐free number if you have any questions or would like to receive some of our resources. From all of us in the Child Welfare Profes‐

sional Development Project, thanks for your patronage! A special toll-free number . . .

(877) 886-6707

. . . is provided for CPS staff and foster and adoptive parents. CWIC

books, DVDs and videos are mailed to

your home or office, along with a

stamped envelope for easy return.

Please specify if you are interested in

receiving foster parent training hours, and a

test and evaluation will be included with the

book or video. Once completed and returned,

foster parents will receive a letter of verification

of training hours earned.

Your calls are important to us.

We look forward to hearing from you!

FOSTER PARENT TRAINING - REACHOUT Newsletter Spring 2010

Complete for one hour of training credit and return to your caseworker.

Learning Objectives

•

The participant will understand the importance of relationships in addressing RAD in children.

•

The participant will understand the connection of child trauma and brain development.

•

The participant will learn the behaviors associated with Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD).

•

The participant will identify the two subtypes of RAD.

•

The participant will discuss goals for effective parenting of children with attachment disorders.

•

The participant will describe the type of parenting that is crucial in assisting children with RAD.

Learning Activities

Activity One

RAD is a disorder of a child’s inability to have relationships.

(Circle the best answer)

True

False

List four behaviors associated with RAD:

1._____________________________________

2. ____________________________________

3. _____________________________________

4. ____________________________________

Activity Two

List and describe the two subtypes of RAD:

1.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Activity Three

Fill in the blank:___________ and ______________ parenting is crucial in helping children with RAD in their growth to become

productive and emotionally healthy adults.

List the normal emotional and social development for children 0-18 months:

1.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lack of empathy and little evidence of guilt and remorse for others are behaviors associated with RAD.

(Circle the best answer).

True

False

Activity Four

Early childhood trauma does not affect the structure of the brain and all the physiological processes.

(Circle the best answer).

True

False

List and describe two of the goals for effective parenting for children with attachment disorders (Levy and Orlans).

1._________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2._________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Evaluation Trainer Child Welfare Professional Development Project, School of Social Work, SFA Date ____________ Name (optional)___________________________________________________________ Newsletter presentation and materials: 1. This newsletter content satisfied my expectations. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 2. The examples and activities within this newsletter helped me learn. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 3. This newsletter provides a good opportunity to receive information and training. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree Course Content Application: 4. The topics presented in this newsletter will help me do my job. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree 5. Reading this newsletter improved my skills and knowledge. ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree ___Strongly agree ___ Agree 6. What were two of the most useful concepts you learned? _________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7. Overall, I was satisfied with this newsletter. ___Strongly agree ___ Agree ___Disagree ___Strongly disagree Comments: __________________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Page 13

REACHOUT NEWS

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

From the Director YOUTH CONFERENCE

(Continued from page 1)

In the Child Welfare Information Center arti‐

cle (pg. 11), SFA graduate assistant Fateemah Helaire writes about new books and DVDs, which can be checked out for training hours. While Fateemah is completing her last semester for a MSW degree, Veronica Macias and Latoya Brooks will be returning your calls to our toll‐free number (877‐886‐

6707) and assisting in locating resources that would best help you with the challenging issues of foster parenting. We encourage your feedback and suggestions regarding training topics for the newsletter and library resources to support your parenting efforts. Most importantly, we are honored to be part of your many accomplishments! Watch for the Foster & Adoptive Training Conference registration brochure in early March ! Saturday April 17th, 2010 Held while the Foster Parent Conference is in session. Children and Youth drop‐off begins at 7:30 a.m. Information will be mailed separately to Region 5 Foster Parents. For more information contact Martha Boudreaux at (409) 951‐3361 Space is limited. Child Welfare Professional Development Project Staff

Becky Price-Mayo, MSW, LBSW-IPR

Director

Veronica Macias

(936) 468-1808

Graduate Assistant

bmayo@sfasu.edu

(936) 468–1846

Child Welfare Information Center

(936) 468-2705 Latoya Brooks

Graduate Assistant

(936) 468–4578

Stephen F. Austin State University School of Social Work Child Welfare Professional Development Project P.O. Box 6165, SFA Station Nacogdoches, TX 75962‐6165 REACHOUT NEWS

Spring 2010

Earn One Hour of

Foster Parent Training

Child Welfare Professional Development Project

School of Social Work, Stephen F. Austin State University

.