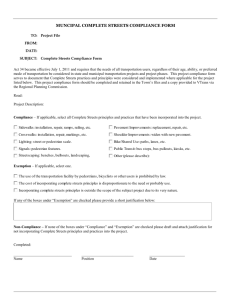

STREETS COMPLETE new haven city of

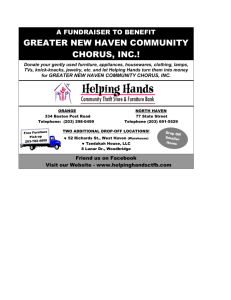

advertisement