A GENDER PERSPECTIVE Who is benefiting from trade liberalization in Bhutan?

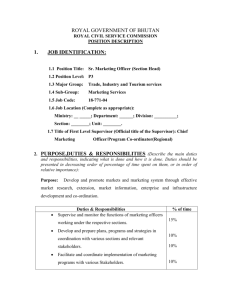

advertisement