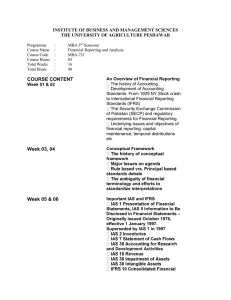

International Accounting and Reporting Issues 2008 Review

advertisement