MOST-FAVOURED-NATION TREATMENT UNCTAD Series on issues in international investment agreements

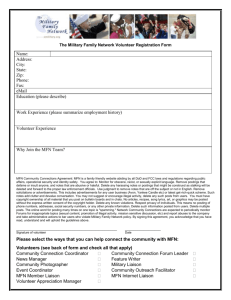

advertisement