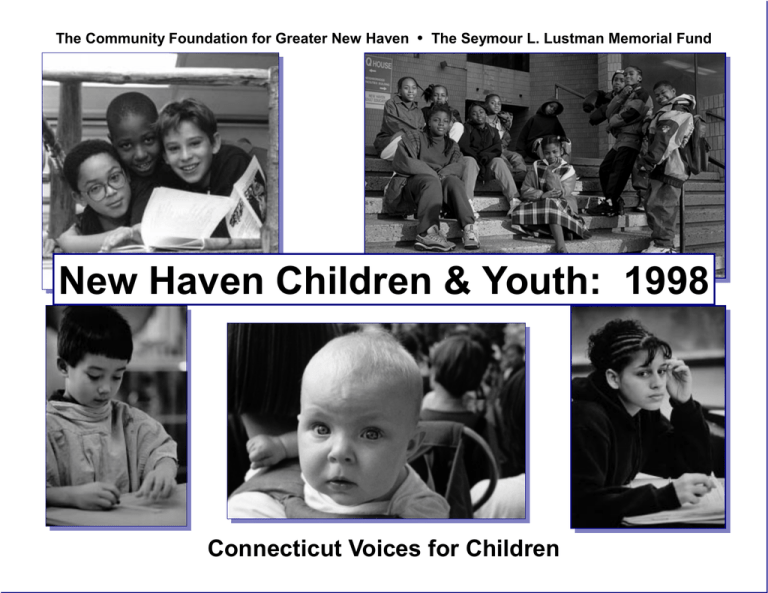

New Haven Children & Youth: 1998 Connecticut Voices for Children

advertisement