The Influence of Preferential Trade Agreements on the Implementation of Intellectual

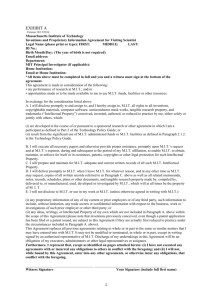

advertisement