Document 10423090

advertisement

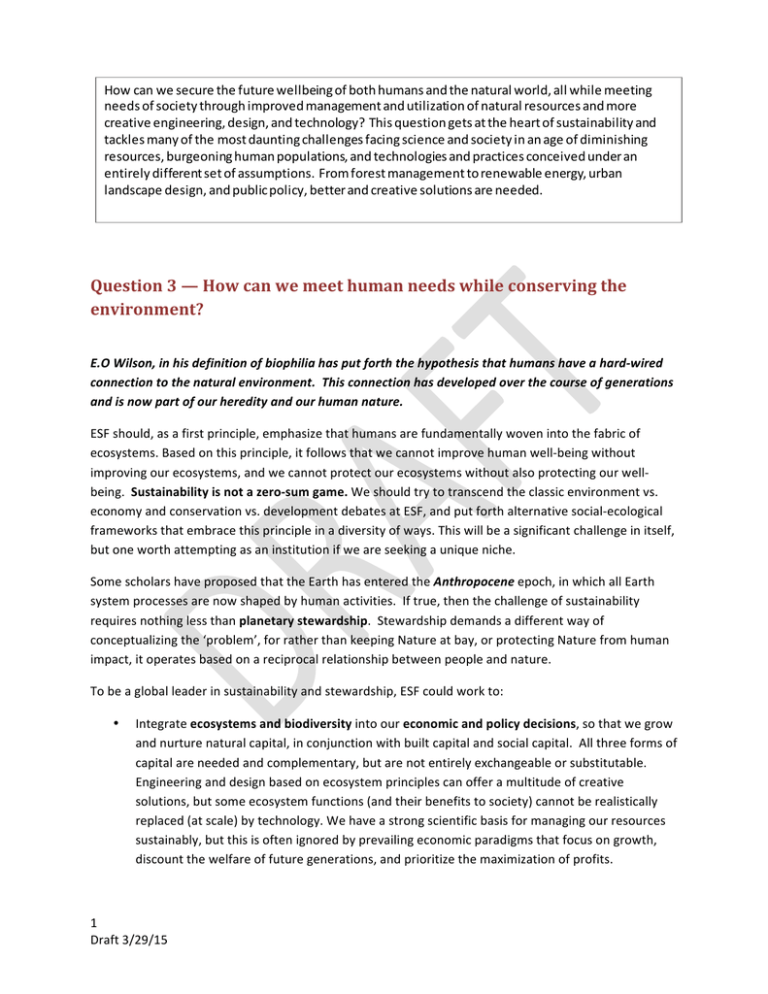

How can we secure the future wellbeing of both humans and the natural world, all while meeting needs of society through i mproved management and utilization of natural resources and more creative e ngineering, design, and technology? This question gets at the heart of sustainability and tackles many of the most daunting challenges facing science and society i n an age of diminishing resources, burgeoning human populations, and technologies and practices conceived under an entirely different set of assumptions. From forest management to renewable e nergy, urban landscape design, and public policy, better and creative solutions are needed. Question 3 — How can we meet human needs while conserving the environment? E.O Wilson, in his definition of biophilia has put forth the hypothesis that humans have a hard-­‐wired connection to the natural environment. This connection has developed over the course of generations and is now part of our heredity and our human nature. ESF should, as a first principle, emphasize that humans are fundamentally woven into the fabric of ecosystems. Based on this principle, it follows that we cannot improve human well-­‐being without improving our ecosystems, and we cannot protect our ecosystems without also protecting our well-­‐ being. Sustainability is not a zero-­‐sum game. We should try to transcend the classic environment vs. economy and conservation vs. development debates at ESF, and put forth alternative social-­‐ecological frameworks that embrace this principle in a diversity of ways. This will be a significant challenge in itself, but one worth attempting as an institution if we are seeking a unique niche. Some scholars have proposed that the Earth has entered the Anthropocene epoch, in which all Earth system processes are now shaped by human activities. If true, then the challenge of sustainability requires nothing less than planetary stewardship. Stewardship demands a different way of conceptualizing the ‘problem’, for rather than keeping Nature at bay, or protecting Nature from human impact, it operates based on a reciprocal relationship between people and nature. To be a global leader in sustainability and stewardship, ESF could work to: • Integrate ecosystems and biodiversity into our economic and policy decisions, so that we grow and nurture natural capital, in conjunction with built capital and social capital. All three forms of capital are needed and complementary, but are not entirely exchangeable or substitutable. Engineering and design based on ecosystem principles can offer a multitude of creative solutions, but some ecosystem functions (and their benefits to society) cannot be realistically replaced (at scale) by technology. We have a strong scientific basis for managing our resources sustainably, but this is often ignored by prevailing economic paradigms that focus on growth, discount the welfare of future generations, and prioritize the maximization of profits. 1 Draft 3/29/15 • • Create more biophilic human communities by defining and implementing ecosystem design principles across the spectrum from urban, to suburban, to rural settings. These principles include, but are not limited to: material cycling, energy flow, regulation of external forcing, (add more here) and the importance of diversity for adapting to change. Foster resilience and adaptive capacity in our built, managed, and natural systems as a fundamental approach for sustainability and stewardship. We should embrace change and uncertainty as basic realities of life on Earth, and recognize that inflexible or non-­‐adaptive strategies for securing our basic needs (food, water, shelter, energy) will ultimately fail. We cannot predict the future with certainty, or always make the most optimal choices, but we can leverage our knowledge and experience to make better decisions. Of the many emerging challenges for sustainability and planetary stewardship, ESF can make novel and leading contributions in several areas, including: • • • • • • • Water-­‐Climate-­‐Food-­‐Energy Nexus Built Environments Ecosystem-­‐Based Design & Engineering Nature’s Benefits (Ecosystem Services) Landscape Change Traditional Knowledge & Ecosystem Stewardship Others… One approach for ESF to address the broader question is to contribute and synthesize evidence of real-­‐ world cases where our diverse knowledge and practice has resulted in success. In other words, we should not only address the problems and challenges that we face, but highlight the opportunities and progress made towards solutions. For example, what have we learned from our work in the forests, cities, farms, etc. where the systems are meeting human needs while improving environmental quality? Where does conservation benefit local people as much as the global community? Where has science informed effective policy and regulatory frameworks that result in positive social-­‐ecological outcomes? What do these and other success stories have in common? ESF is in a unique position to leverage our academic strengths and promote new ways of thinking about humans and nature, especially in reimagining the fundamental relationship as one of interdependence, reciprocal care and responsibilities, resilience and ecological integrity. What additional tools do we have, and do we need to address this fundamental question? 2 Draft 3/29/15 ESF could model answers to the following questions through transdisciplinary institutes: 1. How do we create biophilic communities? How do we reconfigure social-­‐ ecological systems in urban, suburban, and rural landscapes? POTENTIAL ACTION ITEMS: a) Create an Institute for Biophilic Communities (i.e., a Community Planning & Design Center). b) Improve stewardship of our food, shelter, energy, and water supplies/resources, focusing on local resources, conservation, and more efficient delivery systems. c) Develop new innovative service projects for students that generate an environmental ethic and could be pursued by other community groups (children, public administrators, etc). d) Create an Institute for Urban Ecosystems that brings together a range of issues and actors around the sustainability and stewardship of densely populated built environments. e) Expand the College’s focus on food resources, closing the gap from agricultural practices, food production, nutrition, and human consumption. f) Create partnerships to improve the well-­‐being of our aging population, landscape and community design, and access to environmental amenities and benefits. INSTITUTE FOR BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES: a Community Planning and Design Center that works with urban, suburban, and rural communities to integratively and comprehensively address their evolution in terms of climate change issues, the delivery of ecosystem services, the energy and ecological footprints of the built environment, ecosystem rehabilitation, resource management, social-­‐ecological resilience, aesthetic quality, quality of life (community well-­‐being and public health), etc. The goal would be to assist in the development of biophilic communities in the areas that we serve and doing so in a way that helps communities find the best ways to truly integrate ecosystems and human settlement patterns in reality, on the ground. The Institute should include as necessary, participants from the full range of the College’s disciplines and such other collaborators as would enhance our work. The Institute should be established in a way that allows the college to identify compelling projects, seek funding for those projects, and establish project teams and project formats while also remaining accessible to individuals to participate in small projects or to respond to small or short-­‐term questions from the communities we serve. The Institute should find annual venues for the presentation of their work to broader audiences. a. Sustainable Built Environments: We need to learn how to optimize the use of building materials to provide an indoor environment that is healthy, durable, cost-­‐effective and safe. We must also develop building materials that are truly renewable and sustainable (in a manner that extends their service life) as well as cost-­‐feasible. This includes minimizing manufacturing costs and maximizing efficiency of producing building materials from renewable resources. Another key goal is to minimize negative environmental impacts from the manufacture of building materials and the construction process, which includes reducing energy consumption in buildings and designing buildings that produce their own energy. Designing communities that are self-­‐sustaining as demographics and environments change requires a transdisciplinary effort. 3 Draft 3/29/15 What Does ESF Need Short and Long Term to Address this Sub Question? 2. How do we integrate ecosystems and biodiversity into economic and policy decisions? POTENTIAL ACTION ITEMS a) Develop an Institute for Ecological Economics & Stewardship as a nexus for integrating basic and applied research on sustainability with ESF’s teaching and service activities b) Create metrics of social-­‐ecological well-­‐being, e.g., a genuine progress indicator (GPI) c) Develop tools for analyzing product life cycles, measures of self-­‐reported and deduced levels of well-­‐being d) Create innovative tools for measuring and valuing ecosystem services for decision-­‐making. e) Develop methods to improve rural economies while maximizing environmental protection f) Create partnerships with businesses that integrate environmental ethics and conservation within economic goals. g) Continue to expand our efforts in environmental health and environmental medicine. INSTITUTE FOR ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS The world hit 7 billion people around the end of October 2011, and currently is fast approaching 7 ¼ billion humans. That’s a quarter billion additional people – almost 80% the size of the US population – in less than four years. One way of re-­‐thinking how humans and the rest of the biosphere interact is through the paradigm of ecological economics. If we are to make progress towards planetary stewardship, we need to change economic and policy decision-­‐making processes so that the broader and long-­‐term consequences of human actions can be considered in a holistic and balanced way. This goes beyond creating and sharing knowledge, and requires us to devise and promote frameworks that support and justify new ways of approaching tradeoffs and making difficult choices. For example, policy goals must address together the problems of human population growth and consumption. At a global scale, the former is acute in the developing world and the latter acute in the developed world. However, both of these issues arise in the U.S. ESF has a fledgling academic program in Biophysical and Ecological Economics. This could be expanded programmatically into an institute with faculty, students, post-­‐docs, and visiting scholars. Topics that could be addressed include the following: a. Metrics of Social-­‐Ecological Well-­‐Being A e or GPI, is a metric that has been suggested to replace, or supplement, gross domestic product (GDP) as a measure of human progress. GPI is designed to take fuller account of the health of a nation's economy by incorporating environmental and social measures of well-­‐being that are completely ignored by GDP. ESF should build on progress made in Vermont to collaboratively develop a Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) for our local community and NYS. 4 Draft 3/29/15 The process of developing a GPI will draw on all of ESF’s strengths and can engage the students, faculty, staff, our neighboring communities and partner institutions, such as DEC. It could also illuminate key areas of transdisciplinary scholarship that ESF can fill. Based on our own process, ESF could also become a leading institution for teaching about developing GPIs, so that students and scholars could come to learn about creating their own indicators that are tailored to their own situation, whether it be to assess the well-­‐being of a town, a region, a state, nation, or continent. In addition to developing the GPI (one or multiple versions) for Syracuse and NY State, we could also focus on other measures of well-­‐being. We should identify examples at multiple scales of high levels of human well-­‐being, coexisting with low levels of energy and material throughput, or other measures of environmental pressures. For example, at the level of the firm, ESF would need to develop tools for analyzing product life cycles, measures of self-­‐reported and deduced levels of well-­‐being. We would look at the full range of impacts, when looking at consequences of climate change. We might use Onondaga County as our baseline. b. Identifying and Valuing Ecosystem Services Ecosystem services are benefits derived from the natural world. We exploit these all the time, but often the less visible ones are underappreciated until something goes wrong (think climate change). The field of ecosystem service identification, quantification, and valuation connects underlying ecosystem structure and function to human wellbeing. ESF already has capacity in this area and is poised to be a local and regional “go-­‐to” place for this expertise. For example, currently ESF is engaging with Stony Brook University in a SUNY 4E proposal to identify and quantify the ecosystem services of Jamaica Bay. There are also many basic and applied questions about the monetary valuation of, and market-­‐based mechanisms for trading, various ecosystem services. c. Resource Management and Ecosystem Stewardship ESF has long been a leader in sustainable management of natural resources, having been founded to promote better models of stewardship in NY State and beyond. We have trained several generations of resource managers and practitioners, but larger-­‐scale trends in land use and ownership, market globalization, and public opinion have resulted in less than sustainable progress in Linking the two disciplines and endeavors is a critical need that requires transdisciplinary and cross-­‐scale thinking as well as practice. d. Ecosystem-­‐based Life Cycle Analysis (“Eco-­‐LCA”) of Energy Systems This concept is emerging in the renewable energy community, but it could benefit 5 Draft 3/29/15 e. Climate change adaptation f. Furthering the academic program in ecological economics ESF can further develop this capacity by continued participation in national networks, with other SUNYs and other institutions, and perhaps partnering with the Whitman School of Management to develop a joint MBA program. It could also partner with the Newhouse School of Communication to develop a “messaging” program, as society at large will need to buy in to a change from a highly consumptive pattern to a less consumptive one. ESF can be a leader to help design ways in which such changes will not produce great stresses or hardships, but rather transition into a new pattern of living. What Does ESF Need Short and Long Term to Address this Sub Question? a. Short term: establish a group to plan for the Institute for Ecological Economics; identify partner institutions b. Long term: financial resources to hire 2-­‐4 new faculty in this field Questions Arising from Discussion a. How do we conceive of and develop a GPI for NYS – start local for Syracuse? b. How to define, measure c. We need to AVOID the message that conserving the environment is not the best thing for business. Restoration is the more important message. d. The group thought that changing “conserving” to “conserving and restoring” would be valuable. Each of the three sub question requires collaboration and a research thrust to be meaningful. Food, shelter, energy and water are identified as human needs. Understanding patterns of population pressure on environment and resources is fundamental to addressing this question. In every case, ESF needs to bring its strengths to bear. 3. How do we develop resilient and adaptive systems in a changing world? POTENTIAL ACTION ITEMS: a) Develop a Center for Resilient Systems to identify alternative means to define, measure and foster resilience at multiple scales across a variety of managed and built environments b) Build on emerging strengths in environmental communication and participatory processes to develop mechanisms for shaping public awareness of the need for adaptive systems. c) Continue to grow our understanding of anthropogenic influences on the Earth system, the many types of environmental and social change that are likely to occur, and develop knowledge and decision-­‐tools to support more integrated adaptation strategies. d) Improve energy systems, focusing on landscape design for renewable energy, and reducing energy consumption and losses in the built environment. 6 Draft 3/29/15 e) Expand our focus areas in life cycle analysis, systems monitoring and modeling, and cradle-­‐ to-­‐cradle manufacturing and design. f) Develop more sustainable building practices, optimizing building materials, exploring renewable resources, and minimizing costs, while reducing negative environmental impacts. g) Create a Center for Adaptive Management to reinvigorate the concept, implement it in our landscapes and communities, and demonstrate its potential benefits for society h) Identify potential social-­‐ecological vulnerabilities through scenario building and analysis. CENTER FOR RESILIENT SYSTEMS would be a collaborative ‘think-­‐tank’ composed of scholars, students, and practitioners innovating and promoting systems thinking in ways that directly support research, teaching and service at ESF. Recognizing that change and uncertainty are basic realities of life on Earth, we propose that inflexible or non-­‐adaptive strategies for securing our basic needs (food, water, shelter, energy) will ultimately fail – with long-­‐term negative implications for both ecosystems and society, because they are inexorably coupled. We cannot predict the future with certainty, or always make the most optimal choices, but neither can we be paralyzed into inaction. Instead, we can leverage our knowledge and experience to generate more holistic (system) perspectives and make better decisions that sustain the key features and processes of our ecosystems that allow us to thrive, but also allow for flexibility and surprise. Recognizing that systems thinking challenges many aspects of the status quo, a key activity of the Center will be an ongoing discussion (within and outside of ESF) about how the resilience concept can itself be adapted for different disciplines, types of communities, economic sectors, policy domains, etc. What Does ESF Need Short and Long Term to Address this Sub Question? How should ESF share what we learn through these transdisciplinary institutes? Community Engagement ESF should use community engagement to share our academic and professional explorations and educate citizens and decision-­‐makers regarding the value and applicability of the work that we do. Community engagement also informs the ESF community about issues important to the outside world, offering an extramural “feedback loop” of needs and information. Community Engagement can include local, national and international in focus. Community engagement should be seen as a way to disseminate knowledge, offer technical assistance and collaboration to governments, communities, business, industry, and not-­‐for-­‐profits in order to improve the ecosystems, landscapes, and communities of New York State (and beyond), enhance the reputation of SUNY-­‐ESF and garner continued respect and support from the State Legislature. This is one way to significantly leverage ESF’s strengths. Community Engagement is one way for ESF to engage decision makers. 7 Draft 3/29/15 Working closely with communities will provide some insight on what will be on the horizon and might provide opportunities for ESF to address needs. It is one way to better bring our research strengths to bear on the public arena. A similar approach may be transferrable to potential donors. The premise is to cultivate audiences that can “make something happen.” The College has significant credibility in the Adirondacks we are perceived as honest brokers. Community engagement might be structured as follows: (1) department-­‐level relationships with specific communities, not-­‐for-­‐profits, and enterprises; (2) college-­‐wide relationships with the New York State Conference of Mayors, the New York State Association of Counties, the Association of Towns of the State of New York, the Adirondack Association of Towns & Villages, the New York State Urban Forestry Council, the New York Forest Owners Association, etc. – perhaps eventually earning a presentation slot at each of their annual conferences; (3) departmental and / or college-­‐wide relationships with operating departments of New York State such as NYSDOT, NYSDEC, NYSDOS, NYSOPRHP, etc.; (4) college-­‐wide relationships with Federal departments such as the USDA Forest Service, USDOT, HUD, National Park Service, EPA, NOAA, etc. Initiative for Stewardship in Policy and Practice This trans-­‐disciplinary initiative would be focused on getting the best possible information into the hands of decision-­‐makers at multiple levels, and providing them with the support needed to utilize that information in meaningful ways to address tradeoffs and make better decisions towards sustainable outcomes. This would require more faculty investment in the decision sciences, while maintaining our existing capabilities in policy science and resource management. For example, with respect to climate change impacts on food-­‐water-­‐energy issues in NYS, we could work to fill a critical gap left open by Cornell Cooperative Extension, who lags behind nearby states on these issues. 8 Draft 3/29/15