5 LEGAL ISSUES AND REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS

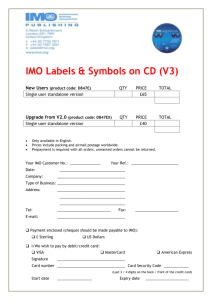

advertisement