REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2011 Chapter 6

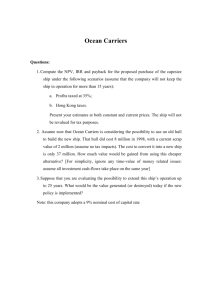

advertisement