P A H

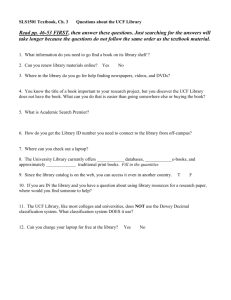

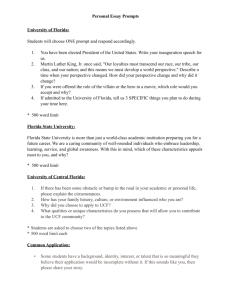

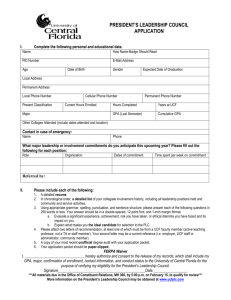

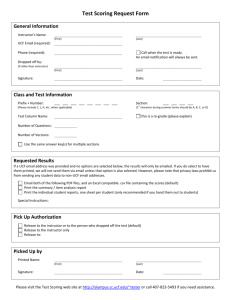

advertisement