SECTION 4: THE EVALUATION PROCESS

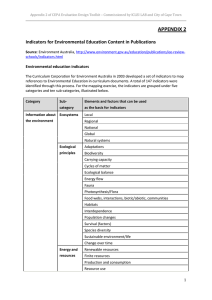

advertisement