REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2013 Chapter 5

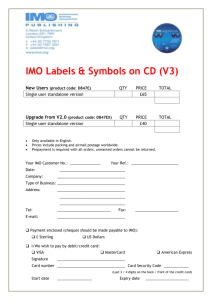

advertisement