Document 10383796

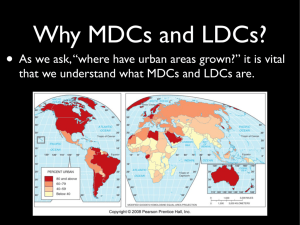

advertisement