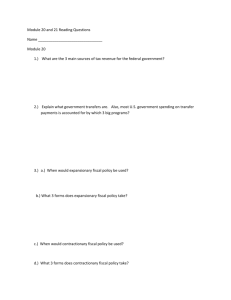

TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT, 2012 Chapter V ThE ROLE OF FISCAL POLICy IN

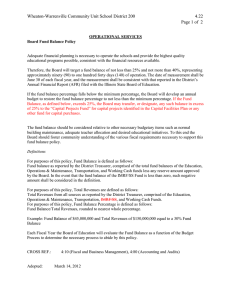

advertisement