IET 35000 Engineering Economics Learning Objectives – Chapter 3 Chapter 3 – Unit 1

advertisement

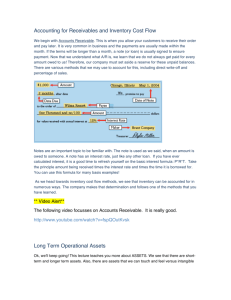

Chapter 3 – Unit 1 The Accounting Equation – Depreciation, Inventory and Ratios IET 35000 Engineering Economics Learning Objectives – Chapter 3 Upon completion of this chapter you should understand: Accounting equation entries applied to capital costs and expenses and their impact on financial statements. Depreciation methods, calculating depreciation and book value of assets and the affect on profit, taxes and cash flow. Inventory management and the affect on the accounting equation. Financial statement ratios and their use for economic decision making. 2 Learning Objectives – Unit 1 Upon completion of this unit you should understand: Accounting equation entries applied to capital costs and expenses and their impact on financial statements. Depreciation methods, calculating depreciation and book value of assets and the affect on profit, taxes and cash flow. Inventory management and the affect on the accounting equation. Financial statement ratios and their use for economic decision making. 3 1 Cash Outflows Organizations spend money (cash outflow) for a variety of needs including: Product or service related items such as materials, wages, and overhead. Administration related items such as wages, supplies, marketing and overhead. Financial related items such as debt payments, dividends and financial securities. Permanent equipment, land and facilities. 4 Cash Outflows Cash outflows are categorized as: Expenses – includes cash outflows for items that are used within a short time period such as supplies and raw materials, or for services such as labor, wages and utilities. Capital – includes cash outflows for items that are permanent or will be used over an extended time period such as equipment, buildings and land. Also business start‐ up costs and cost of improvements are capitalized. 5 Cash Outflows Expense: Entire cash outflow is included as a cost or expense on the income statement during the time period in which the transaction occurs. Expensing is the term for an expenditure that reduces cash and increases a cost account of the Accounting Equation. Since an expense is immediately reflected on the income statement, net income is reduced resulting in a reduced income tax liability. 6 2 Cash Outflows Capital: Cash outflow is included as an asset on the sheet for the time period in which the transaction occurs. Capitalizing is the term for an expenditure that reduces cash and increases an asset account of the Accounting Equation. Since a capital expenditure is not reflected on the income statement, there is no change in net income and therefore not change in the income tax liability. The cost of a capital expenditure is accounted for by depreciation, amortization or depletion. 7 Expensing or Capitalizing? Decisions whether to expense or capitalize cash expenditures are based in part on the following criteria: Life – short life or immediately consumed is an expense. Long life is capitalized. Value – expensive equipment is capitalized and low cost items are expensed. Many firms establish a dollar cut‐off amount for expensing versus capitalizing. IUPUI uses a $5,000 minimum amount to be capitalized and tracks all capital items with an inventory tag. 8 Expensing or Capitalizing? Criteria (continued): Matching considerations – items are expensed or capitalized so that the costs occur in the same time period as revenues from selling output. Accounting conventions – GAAP and company policies may determine whether to expense or capitalize. Special situations – unique and one‐time events may determine whether to expense or capitalize. Internal Revenue Service guidelines. 9 3 Why Capitalize? Initially it may seem that expensing all cash outflows would be beneficial since an expense has the affect of reducing tax liability. Generally, capitalizing expenses with long‐life spans is preferable to avoid the immediate negative affect on net income. Matching the use of a capital asset to the time period of its use through depreciation, amortization or depletion accurately reflects the true cost to the organization. 10 Why Expense? Expensing cash outflows is beneficial since an expense has the affect of reducing tax liability. An expense can only be included on the income statement one time so even if the asset continues to be used, it will no longer affect net income. Capitalizing regular operating expenses will have the affect of increasing cash flow and creating the appearance of profitability. This distorts the true financial condition of the organization and, because the capitalized expenses will affect future periods net income, this approach is equivalent to paying for items that have long since been used. 11 Expensing or Capitalizing? The Internal Revenue Code, Treasury Regulations (including new regulations proposed in 2006), and case law set forth a series of guidelines that help to distinguish expenses from capital expenditures, although in reality distinguishing between these two types of costs can be extremely difficult. In general, four types of costs related to tangible property must be capitalized: 1. Costs that produce a benefit that will last substantially beyond the end of the taxable year. 2. New assets that have a useful life substantially beyond one year. 3. Improvements that prolong the life of the property, restore property to a “like‐new” condition, or add value to the property. 4. Adaptations that permit the property to be used for a new or different purpose. Reference: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expenses_versus_Capital_Expenditures 12 4 Timing Cash Accounting System – sales of product or service is recorded when payment is received. Could result in cost and revenues which are not matched or synchronized regarding time periods. Accrual Accounting System – sale of product or service is recorded when the shipment is made or the service delivered through accounts receivable entries. This system results in better matching costs and revenues in the same time period. 13 End Unit 1 Material Additional Reading Chapters 1 and 7 of IRS Publication 535 Business Expenses Go to Unit 2 Depreciation 14 Chapter 3 – Unit 2 Depreciation IET 35000 Engineering Economics 5 Learning Objectives – Unit 2 Upon completion of this unit you should understand: Accounting equation entries applied to capital costs and expenses and their impact on financial statements. Depreciation methods, calculating depreciation and book value of assets and the affect on profit, taxes and cash flow. Inventory management and the affect on the accounting equation. Financial statement ratios and their use for economic decision making. 16 Noncash Outflows Costs associated with assets that have been capitalized are recovered over time by including a noncash expense on the income statement. Noncash outflows include: Depreciation – used for tangible assets such as buildings and equipment. Amortization – used for intangible assets such as patents, trademarks and copyrights. Depletion – used for productive land assets such as timber, minerals and oil. Optional Reading Chapters 8 and 9 of IRS Publication 535 Business Expenses contains more information on amortization and depletion. 17 Depreciation Depreciation is a noncash expense that is included in the accounting equation for a fiscal time period. Accounting equation entries are: Depreciation is added as a cost to be assigned to the income statement. Depreciation is subtracted from the asset account ultimately reducing the total asset value on the balance sheet. 18 6 Depreciation Depreciation concepts: Depreciation is not a cash flow. No one writes a check or transfers money to ‘depreciation’. It is an adjustment to the financial statements to represent the expensing of a previous capital cash outflow. Several methods of determining the depreciation amount exists. Since the depreciation method selected affects net income and therefore taxes, the IRS requires specific depreciation methods. Depreciation applies only to assets used for business. Personal assets such as a home cannot be depreciated. 19 Depreciation Depreciation terminology: Basis or Asset Value – cost of acquiring and installing the asset. When cost is not available, fair market value is used. Asset Life – estimated useful life of the asset in years. Salvage Value – estimated asset value plus the cost to remove or dispose the asset at the end of its life. Note that a salvage value can be zero. Book Value – basis minus accumulated depreciation for an asset. 20 Depreciation Live and salvage value estimates are based on: Physical considerations – durability, quality, reliability, expected level of use, history, vendor recommendation. Economic considerations – even though the asset may physically be functional, increasing maintenance costs may result in replacement. Replacement policies – periodic replacement of vehicles based on time or mileage. Periodic replacement of assets that technology evolve such as computers. Technological considerations – obsolescence due to newer technologies – computers, software. 21 7 Depreciation Depreciation calculation methods: Straight‐Line (SL) – allowable in current tax code. Sum‐of‐Years‐Digits (SOYD) – not currently allowed by the IRS except for assets put into service prior to 1986. Declining Balance (DB) – not currently allowed by the IRS except for assets put into service prior to 1981. Unit‐of‐Output Method –currently allowed by IRS. Accelerated Cost Recovery System (ACRS) – replaced by MACRS. Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) – current accelerated depreciation system allowed by IRS. 22 Straight‐Line Method Simplest depreciation method. Depreciation is a constant amount each year. Life and salvage value are estimated at time of purchase. Depreciation is then found by: Basis ‐ Salvage Value Depreciation/year Life Note: Straight‐line depreciation equation on page 85 of Bowman text has an error. Equal sign between ‘First Cost’ and ‘Salvage Value’ should be a minus sign. 23 Sum‐of‐Years‐Digits Method Introduced in 1950 and used through 1980’s. Only allowed by IRS for assets put into service prior to 1986. Referred to as accelerated depreciation method since more depreciation cost occurs in earlier portion of asset life. Asset life in years is estimated at time of purchase. Sum of years is then found by: nn 1 Sum of Years 2 where : n estimated life in # years 24 8 Sum‐of‐Years‐Digits Method Sum of years and estimated salvage value are then used to determine the depreciation amount for each year: n 1 ‐ j Depreciation in year j Basis ‐ Salvage SY where : n estimated life in # years SY Sum of years value 25 Method Comparison Straight‐Line depreciation yields a constant amount while Sum‐of‐Years‐Digits results in accelerated depreciation. Compare the plots of the two methods from the text example where basis = $100,000, life = 10 years and salvage = $10,000 Bowman page 86 Bowman page 93 26 Declining Balance Method Introduced in 1950’s and used through 1981. Only allowed by IRS for assets put into service prior to 1981. Like Sum‐of‐Years‐Digits, Declining Balance is an accelerated depreciation method and is the basis of the current modified accelerated cost recovery method. Declining Balance method employs a multiplication factor of 1.25, 1.5, 1.75 or 2.0 with a Straight‐Line depreciation amount. When a multiplication factor of 2.0 is used, the method is referred to as the Double Declining Balance method. 27 9 Declining Balance Method Salvage value is not used with this method. Remember that the book value is the initial basis less the accumulated depreciation. The calculation is repeated for each year of the estimated life of the asset. Book Value Depreciation DB Factor Life 28 Unit‐of‐Output Method Incorporates the actual use of the asset to determine depreciation. Examples: Depreciation per sheet on a copy machine. Depreciation per hour on a jet engine. Depreciation per piece on a production line. Logically this method will match the depreciation expense with the actual use of the asset. Disadvantage is the requirement of monitoring the actual use of the asset. IRS allows unit‐of‐production (their term) depreciation if the method is elected when asset is put into service. 29 MACRS Method Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) was established in 1986 and is the method approved by the IRS. MACRS method classifies assets into categories and specifies the life to be used in the depreciation calculation (Table 3‐3). Bowman page 94 30 10 MACRS Method MACRS table provides percentages that are used with the basis to determine annual depreciation amounts (Table 3‐4). 31 Bowman page 95 MACRS Method Depreciation for a specific year is simply the basis multiplied by the MACRS factor for that year: Depreciationyear i Basis MACRS Factoryear i Book value is determined as before, basis less accumulated depreciation: Book Value year i Basis ‐ Accumulated Depreciation 32 Compare the book value plots of the various methods using the text example (basis = $100,000, life = 10 yrs, salvage = $10,000): $100,000 Straight Line $90,000 $80,000 Sum of Years Digits $70,000 Declining Balance (1.5 Factor) Book Value $60,000 Double Declining Balance $50,000 MACRS $40,000 $30,000 $20,000 $10,000 $0 33 Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 Selling Assets Since the book value of a capitalized asset is based on accumulated depreciation which was determined by a formula, actual value typically does not equal book value. If an asset is sold or salvaged, the transaction requires entries in the accounting equation which ultimately affects the financial statements. If the asset is salvaged for exactly the book value, cash is increased and assets are decreased by that amount. 34 Selling Assets If the asset is salvaged for more than the book value, the revenue minus the book value is the ‘profit’ from the sale. 35 Selling Assets If the asset is salvaged for less than the book value, the revenue minus the book value is the ‘loss’ from the sale. If an asset is retained by the company beyond its estimated life, it is carried on the books at its fully depreciated book value which could be zero. If an asset undergoes a major rehabilitation or upgrade which extends the life of the asset, the cost associated with the activity is also capitalized and depreciated over time. 36 12 Microsoft Excel® Hints Excel® has several built‐in depreciation functions including: SLN(cost, salvage, life) straight‐line depreciation for one period. DB(cost, salvage, life, period, month) fixed‐declining depreciation for a specified period. DDB(cost, salvage, life, period, factor) declining balance depreciation for a specified period. SYD(cost, salvage, life, per) sum‐of‐years’ digits depreciation for a specified period. VDB(cost, salvage, life, start_period, end_period, factor, no_switch) double‐declining balance depreciation for a specified period including partial periods. 37 Example Problem 3.1 Example Problem 3.1 Solution 38 End Unit 2 Material Additional Reading Chapter 1 of IRS Publication 946 How to Depreciation Property Go to Unit 3 Inventory 39 13 Chapter 3 – Unit 3 Inventory IET 35000 Engineering Economics Learning Objectives – Unit 3 Upon completion of this unit you should understand: Accounting equation entries applied to capital costs and expenses and their impact on financial statements. Depreciation methods, calculating depreciation and book value of assets and the affect on profit, taxes and cash flow. Inventory management and the affect on the accounting equation. Financial statement ratios and their use for economic decision making. 41 Inventory Accounting Inventory represents a major asset category. Inventory cost dependent on the inventory accounting system used. Product cost and price also dependent on the inventory accounting system used. Inventory accounting system varies depending on the type of business: Retail or wholesale distribution. Manufacturing. 42 14 Inventory Accounting Retail or Wholesale Distribution Accounting equation entries when inventory purchased: Decrease cash asset account by purchase cost. Increase inventory asset account by purchase cost. Accounting equation entries when inventory sold: Decrease inventory asset account by inventory cost. Increase cost of goods sold cost account by inventory cost. Increase cash asset account by sales price. Increase sales revenue account by sales price. 43 Inventory Accounting Retail or Wholesale Distribution – text example (figure 3‐5): Purchase inventory for $1,000. Sell inventory for $1,500 and adjust inventory for the sale by $1,000. 44 Inventory Accounting Manufacturing Finished goods inventory value includes all the costs required to convert raw material into sellable product. Figure 3‐7 Manufacturing Inventory Cost Pipeline 45 15 Inventory Accounting Manufacturing Accounting equation entries when raw materials are purchased: Decrease cash asset account by purchase cost. Increase inventory asset account by purchase cost. Accounting equation entries as material moves through manufacturing sequence: Decrease cash asset account by labor and overhead costs as they are expended. Increase inventory asset account by labor and overhead 46 costs. Inventory Accounting Manufacturing (continued) Accounting equation entries when finished product inventory sold: Decrease inventory asset account by inventory cost. Increase cost of goods sold cost account by inventory cost. Increase cash asset account by sales price. Increase sales revenue account by sales price. 47 Inventory Accounting Manufacturing – text example (figure 3‐6): Purchase raw material inventory. Add labor cost and overhead expense required for completion. Adjust inventory and cost of goods sold by finished inventory cost. Adjust sales and cash accounts by selling cost. 48 16 Inventory Accounting Manufacturing (additional concepts) Most manufacturing organizations accumulate costs by production lot. Raw material issued would be moved to a work‐in‐process (WIP) inventory account for each production lot. Labor costs and overhead expenses would be assigned to WIP inventory account. Finished inventory cost would then be based on accumulated production lot costs. Cost of goods sold becomes more complex in this system. 49 Inventory Accounting Manufacturing (additional concepts) Raw Material Inventory Account WIP Inventory Account ‐ Lot 12345 WIP Inventory Account ‐ Lot 34567 WIP Inventory Account ‐ Lot 56789 Direct Labor Cost + Overhead Expense Direct Labor Cost + Overhead Expense Direct Labor Cost + Overhead Expense Finished Goods Inventory Account 50 Example Problem 3.2 Example Problem 3.2 Solution 51 17 End Unit 3 Material Go to Unit 4 Financial Statement Ratios 52 Chapter 3 – Unit 4 Financial Statement Ratios IET 35000 Engineering Economics Learning Objectives – Unit 4 Upon completion of this unit you should understand: Accounting equation entries applied to capital costs and expenses and their impact on financial statements. Depreciation methods, calculating depreciation and book value of assets and the affect on profit, taxes and cash flow. Inventory management and the affect on the accounting equation. Financial statement ratios and their use for economic decision making. 54 18 Financial Statement Ratios Income Statements, Balance Sheets and Cash Flow Statements give us the financial history of the organization. Sound management decision‐making requires comparison financial data from these statements: Horizontal Analysis – comparing changes in financial statements between periods of time. Vertical Analysis – comparing changes in percentage of cost or profit to net income within a time period. Benchmarking – comparing financial results to other organizations or industry averages. 55 Financial Statement Ratios Categories of ratios and percentages commonly used: Liquidity – evaluates how much cash or near cash is available to the organization. Profitability – include return on assets, sales, investment and similar ratios. Assets – measures asset management. Debt –measures debt to asset ratios and use of debt. Security – evaluates the financial condition of the organization from the owners (shareholders) perspective. 56 Liquidity Ratios Current Ratio Measures how many current assets would remain if all current liabilities are paid. Historically a conservative CR 2.0 has been the target. Liquidity ratios are usually acceptable when cash flow is sufficient. Current Ratio Current Assets Current Liabilitie s 57 19 Liquidity Ratios Quick Ratio More conservative than Current Ratio since inventory is removed from current assets. Philosophy is that inventory may not be quickly liquidated. Liquidity ratios typically become too low when cash flow is weak indicating potential liquidity problems. Quick Ratio Current Assets ‐ Inventories Current Liabilitie s 58 Profitability Ratios Profit Ratio Reports on profit as a percentage of sales either before or after taxes. Very common ratio reported by press and used to compare organizations and segments of industry. Net Income Profit Ratio Sales 59 Profitability Ratios Earning Power Percentage Measures how well the assets are used to produce profit. “King” of financial ratios since it includes profit from the income statement and total assets from the balance statement. Profit Before Tax and Interest Earning Power Total Assets 60 20 Profitability Ratios Return on Assets Percentage Similar to Earning Power percentage. No significant financial transaction can occur without affecting the Earning Power and Return on Assets. Low Earning Power and Return on Assets indicate that the organization may not be effectively using its assets. Return on Assets Net Income Total Assets 61 Profitability Ratios Return on Equity Percentage Measures how well the owners’ investment (common stock) is turned into profit. Average Return on Equity is approximately 12% in the U.S. Lower Return on Equity may indicate management issues. Return on Equity Net Income Common Equity 62 Asset Ratios Inventory Turnover Ratio Inventory Turnover measures the organization’s inventory management (asset) and the ability to meet customer delivery requirements. High ratios indicate assets (cash) tied up in inventory which have no return on investment. Low ratios indicate the potential inability to meet customer delivery requirements. 63 21 Asset Ratios Inventory Turnover Ratio (continued) U.S. average Turnover Ratio is 6 to 8 times per year. Notable exceptions include Dell Computer who utilizes a build to order philosophy (high turnover ratio). Implementing lean and just‐in‐time manufacturing systems will also increase the Turnover Ratio (20 to 100 range) without affecting customer service. Sales Inventory Turnover Ratio Inventory 64 Asset Ratios Days of Receivables Outstanding Measures the average time it takes a customer to pay for the product purchased in days. Can be used to measure economic conditions and potential cash flow . Days of Receivables Outstanding Accounts Receivable Average Sales per Day 65 Asset Ratios Revenue to Assets Ratio Shows the amount of assets that are required to support a given level of sales. Revenue to Assets Ratio Sales Total Assets 66 22 Debt Ratios Debt to Asset Percentage Generally liabilities are acceptable if they produce a return and the organization is able to pay the interest and principle. Debt to Asset Ratio measures the percentage of assets that come from borrowed funds. Debt to Assets Total Debt Total Assets 67 Debt Ratios Debt to Net Worth Percentage Measures proportion of external financing from debt funding to total net worth. High percentages indicates heavy reliance on debt financing while low percentages indicate reliance on capital and profits. Total Debt Debt to Net Worth Net Worth 68 Security Ratios Earning per Share (EPS) Security ratios are from viewpoint of the shareholder/owner. Earnings per Share is a measure of short‐term success of the organization and is widely reported and followed. Net Income Earning per Share Number of Shares 69 23 Security Ratios Price Earnings (PE) Ratio Earnings per Share is a measure of market price to earning power of the organization and is widely reported and followed. Market Price per Share Price Earnings Ratio Earnings per Shares 70 Security Ratios Book Value Theoretical amount owners would receive if the firm was liquidated. Book Value units are $/share. Owners' Equity Book Value Number of Shares 71 Security Ratios Payout Percentage Reports on the percentage of profits paid out as dividends. Asset‐intensive firms such as utilities typically have large payouts while small and start‐up firms may have no or low payouts. Dividends Payout Net Income 72 24 Security Ratios Yield Percentage Analogous to interest on a bond or savings account. Earnings may have an affect on the stock price – higher earnings could result in an increase of the stock market price. Dividend per Share Yield Market Price 73 Traditional Measurements Whatever gets measured usually gets managed. Financial statement based ratios goes back to the DuPont formula developed in the 1920’s for Return on Equity: Return on Equity Profit Ratio Revenue to Assets Assets to Equity Sales Total Assets Net Income Sales Total Assets Common Share Equity Net Income Common Share Equity Goal was to manage each component so Return on Equity is maximized. 74 Manufacturing Measures Several measures are typically used to monitor and manage manufacturing operations. Common measures may include: Productivity – ratio of output/input. Scrap Expense to Production Volume. Inventory ratio comparing WIP and total inventory. Indirect to Direct Labor ratio. Any ratio that provides meaningful data for managing an operation, department, function or firm can be developed and used. 75 25 Example Problem 3.3 Example Problem 3.3 Solution 76 End Chapter 3 Material Student Study Guide Chapter 3 Homework Assignment Problem Set 3 77 26