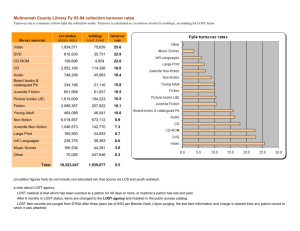

REASONS GIVEN FOR EMPLOYEE TURNOVER IN A FULL PRICED DEPARTMENT STORE

advertisement