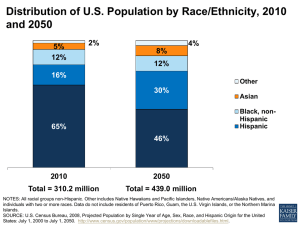

20% 13% 8% Population

advertisement