A Brief Reading on the Subject of

advertisement

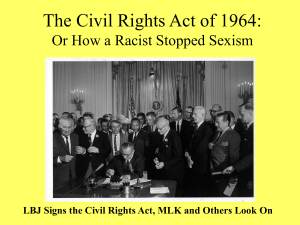

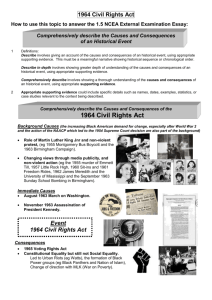

A Brief Reading on the Subject of the Legislative History of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Excerpts from Robert D. Loevy The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law the Ended Racial Segregation (State University of New York Press, 1997) With Commentaries by Hubert H. Humphrey, Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., and John G. Stewart Introduction: Any effort to marginalize the history of the racial oppression of African‐Americans in the United States in the current dialogue about racial equality is contradicted by the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Indeed, Professor Robert Loevy introduces this legislative history with the image of a Dutch ship entering the harbor at Jamestown, and the sale of 20 African slaves to the Virginia Colonists. His brief reminders of the first economic exploitation of chattel slavery to support a southern agricultural economy, and the conflict with a northern economy supported by work for wages is important, but more noteworthy is his reminder that Jefferson’s condemnation of the slave trade in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence was deleted to secure the support of southern colonies for the War against Britain. Also of unique importance to the modern struggle for civil rights, and particularly the jurisprudence related to the Civil War Amendments, is his observation that the framers of the Constitution provided for the eventual abolition of the slave trade per se, but allowed the institution of slavery to remain. Professor Loevy’s discussions of the Civil War Amendments, and Reconstruction, underscore our readings of the assigned cases and Klarman – emphasizing the early efforts of the Republican majority in Congress to respond to the “Black Codes” by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, but the subsequent abandonment of the Party’s efforts to protect black civil rights in the South in favor of seeking the support of white voters generally. With the securing of a Democratic majority following Grover Cleveland’s defeat of Benjamin Harrison, national political interest in black civil rights was unremarkable, as black voter power was suppressed by poll taxes, literacy tests and “white‐only” primaries. Reaffirming the relevance of our early readings, Professor Loevy also views the Supreme Court’s decisions in The Civil Rights Cases of 1883 and Plessy v. Ferguson’s doctrinal facilitation of Jim Crow segregation laws as a necessary part of the backdrop for the legislative consideration of Civil Rights legislation during the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies. Loevy describes this era as facilitating Southern enforcement of racial segregation, even by violence, without any real threat of federal intervention or punishment – and he calls the interests of southern blacks at the beginning of the 20th Century as “governmentally isolated” (i.e., unprotected by the federal government). Professor Loevy’s brief retracing of what he calls the “renationalization” of the civil rights issue from 1900 – 1960 generally recalls the background forces and legal history we have read and discussed, including the formation of the N.A.A.C.P. in 1909, and the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, holding that a state with a white’s only law school was constitutionally required to insure that a “separate” black facility was “equal” to the white facility. But Professor Loevy is quick to emphasize the emergence of a southern reliance on “states’ rights” (beginning at the start of the 20th Century) as the political strategy for resisting any efforts by the national government. Setting the political backdrop for the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Loevy emphasizes – more so than Bass and Klarman – the influence of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in expanding jobs for black citizens and his emerging popularity among black workers in 1936, as the early civil rights movement was taking shape. Loevy especially notes Roosevelt’s use of executive powers to appoint blacks to federal jobs, and his establishment of a Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department. Loevy suggests that, although Roosevelt’s actions were prompted by a direct campaign for civil rights led by A. Phillip Randolph, the most prominent black labor leader in America, Roosevelt’s attempts to establish the first federal Commission on Fair Employment Practices, and Truman’s later creation of a presidential committee on civil rights were initiatives which encouraged black Americans to regard the presidency as supportive of their struggle for racial equality, particularly in employment. At the same time, Loevy notes, black Americans, particularly in the South, saw the Congress and Senate as advancing a “states’ rights” politics for the purpose of resisting federal initiatives to end segregation. Loevy treats the seminal events in the civil rights movement after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board as noteworthy in any discussion of the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but his very brief discussion needs no repetition in light of our readings. It is, however, worth mentioning that, prior to the Little Rock crisis, President Eisenhower had supported civil rights legislation suggested to him by his Attorney General, Herbert Brownell (a champion of civil rights), providing for: (I) The creation of a bipartisan U.S. Commission on Civil Rights; (II) the creation of a Civil Rights Division within the Department of Justice; (III) the delegation of authority to the Attorney General to seek injunctions in federal court in civil rights cases, directly or by removal; and (IV) specific authority for the DOJ to seek injunctions against actual or threatened interference with the right to vote. The passage of this legislation by the House in 1957 was met in the Senate by the emergence of the soon to be legendary opposition of Senator James O. Eastland of Mississippi, who had used his power as chair of the Judiciary Committee to “kill” every civil rights bill during the 1950’s. Opposition focused on Part III, and is illustrated by reference to the statement of Georgia Senator Richard Russell that “The bill is cunningly designed....to force a commingling of white and Negro children in the state supported schools of the South.” Russell’s arguments convinced Eisenhower to withdraw his support for Part III of the bill, and his later public statements in response to the Little Rock crisis is the subject of our readings and documentaries. Despite Eisenhower’s partial retreat on the issue of school desegregation, Loevy sees the creation of the Civil Rights Commission and the creation of the Civil Rights Division of the DOJ as vital to the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In keeping with our prior readings, he emphasizes the Division’s role during the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies as an essential part of the eventual enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Loevy also emphasizes the importance of the Eisenhower administration’s 1959 proposal to extend the Commission as being the occasion for the emergence of Representative Emanuel Cellar’s leadership –and his subcommittee’s role in the eventual proposal of the expansive Civil Rights legislation in 1963 which became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Loevy describes the immediate background for the Kennedy White House legislative initiatives on civil rights as “having few parallels in American history.” Although such a description might be criticized as slighting the courage and sacrifices of black Americans in the decades prior to 1960, Loevy’s intention is to emphasize the escalation of southern opposition – and violence – in 1960‐65, the new role of the Justice Department (as described in some detail by Professor Bass in Unlikely Heroes), and the emerging role of the media as the forces which created the need for the strongest civil rights legislation in modern American history. The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights: Joseph Rauh is perhaps best known for his introduction of Fannie Lou Hamer at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. But his role in the legislative history of the 1964 Civil Rights Act transcends that brief televised moment. As the chief lobbyist for the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, Joseph Rauh led the major lobbying effort on behalf of the bill that eventually became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Mr. Rauh emphasizes, from the outset, that despite President Kennedy’s awareness of the need for legislative action on civil rights for black citizens, Kennedy was hesitant to submit any bill which would be vulnerable to defeat. To the dismay of the Leadership Conference, the bill submitted by the White House fell short of containing the promises of the Democratic Party platform (including authority for the Attorney General to file civil litigation seeking injunctions to prevent any violation of federal civil rights under the Constitution or federal law, and the establishment of a Fair Employment Practices Commission). Instead, the Kennedy bill sought only “patchwork” improvements in existing voting legislation, technical assistance to school districts regarding efforts to desegregate, and an extension of the Civil Rights Commission. Rauh suggests that meaningful proposals might have been lost at this point, had it not been for the events in Birmingham – where the insistence of Dr. King for peaceful mass protests for civil rights was met by the violent retaliation of police commissioner “Bull” Connor. Following international media depiction of Connor’s attacks on protesters, Kennedy remained reluctant to expand his proposed legislation, but deepened his resolve to secure its passage – recognizing that the moral issue at stake was too important to be restrained by concerns for his re‐election. On the merits of the legislation, the emphasis was on the perceived need to create a federal fair employment practices commission, and to authorize the Attorney General to file litigation directly on civil rights issues – and the demand for such expansion of the legislation was evident at the historic March on Washington in August, where Dr. King spoke to a crowd of 250,000 which included members of the U.S. House and Senate. Mr. Rauh also emphasizes that civil rights leaders saw authority for the legislation in both the Fourteenth Amendment and the Commerce Clause, and opposed the position taken by the Kennedy administration that the public accommodations section of the bill be bottomed exclusively on the Commerce Clause. As John Stewart’s notes indicate, Kennedy’s principal concerns, in part responsive to the events in Birmingham in June, were to provide legal authority for desegregating places of public accommodation and public facilities; to provide additional authority for the federal government to combat discrimination against black voting applicants; to assist in school desegregation suits; and to secure nondiscrimination in the operation of federal programs. His June message had also proposed fair employment practices legislation. The eventual legislation urged by House and Senate leadership (without the direct support of President Kennedy) contained the FEPC provisions, broad provisions regarding equal access to public accommodations, and provisions authorizing civil actions directly initiated by the Attorney General. The President intervened and negotiated a compromise bill which limited the Attorney General’s role to intervention, and scaled back the provisions related to public accommodations and FEPC enforcement ‐‐ but any effort at further legislative action would fall to Lyndon Johnson, when Kennedy was assassinated in November. Johnson’s resolve to pass civil rights legislation was particularly important as presidential leadership now came from a Texan, and not a “northern liberal.” His determination, and the leadership of Senators Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, and others resulted in a bill with reasonably strong enforcement provisions, including authority for the Attorney General to directly challenge “pattern or practice” discrimination, and to intervene in private litigation. Senate Consideration of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota assumed the role of “Democratic whip” in the Senate in 1961, and was named by Democratic leader Mike Mansfield to be floor leader for the bill that became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Senator Humphrey, who would later become Vice‐President to Lyndon Johnson, begins his commentary in the summer of 1963, recalling early meetings between President Kennedy, the Attorney General (Robert Kennedy), Senator Humphrey, and a bipartisan group of Senators (four Democrats and Five Republicans) about the possibility of federal civil rights legislation. Senator Humphrey writes that, from the beginning, he felt that the issue was a moral issue and that he urged the President to propose broad, comprehensive legislation, including the restoration of the concept of Part III of the original Brownell proposal to Eisenhower. Humphrey then describes the Senate consideration of the Kennedy proposal, beginning with hearings in the House in the summer of 1963. In Humphrey’s words, with leadership from the President (until his assassination on November 22, 1963), the Attorney General, Deputy Attorney General Katzenbach, Assistant Attorney General Marshall, and House Democratic leaders, including Representative Cellar, “a good bill came from the House” in early 1964. Humphrey recalls his expectation of immediate significant opposition to the bill. Management of the forthcoming floor debate included the appointment of “team captains” responsible for particular titles of the bill, and regular conferences with staff members (including John Stewart), representatives of the DOJ, Joseph Rauh, and leaders of organized labor and the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish communities. During the first two weeks Humphrey and selected colleagues held the floor and engaged in a detailed explanation of the bill – to gain public attention and also to engage the Southerners in debate ab initio. The early strategy also included the significant involvement of Republicans who supported the bill, led by Senator Thomas Kuchel of California, Humphrey’s “co‐partner” in the bipartisan effort. Regular meetings of the bipartisan group and Joseph Rauh’s Leadership Committee were critical. The southern opposition was singularly characterized by the use of the filibuster to prevent a vote on the proposed legislation, and Humphrey recalls the use of newsletters to expose this tactic, but he suggests that the tactic was puzzling and less than effective in the end, because it failed to focus on proposed amendments as a more effective use of the legislative process. The leadership team deliberately chose not to promote “name‐calling” and instead focused on the continuity of strong bipartisan leadership, including Humphrey’s praising of the role of Republican Senator Everett Dirksen for his recognition of the moral issue at stake ‐‐ and he invited Dirksen to assume a prominent role in the Senate’s consideration of the bill. Humphrey is also quick to emphasize in his commentary the need to maintain contact with key state leaders, and the church, and he is clear in his insistence that without the support of clergy, the bill would not have been passed. Finally, Humphrey notes that, while the president was kept informed by regular reports, he was not asked to become directly involved in the Senate’s consideration of the bill. In the end, an agreement was reached to support certain amendments to the bill, including the jury trial amendment, and additional Republican support provided sufficient (71) votes for cloture, and the Senate voted for cloture on June 10, 1964, three months after the bill had come before the Senate on March 9. In the conclusion of his doctoral dissertation, John Stewart noted that it was only because of the ability of pro‐civil rights leadership to respect the traditional independence of their Senate colleagues that efforts to overcome the Senate filibuster succeeded. Impact of the Civil Rights Act: Professor Loevy begins his discussion of the immediate impact of the Civil Rights Act with the statement that it almost immediately eliminated racial discrimination in places of public accommodation throughout the United States. While he cites the Supreme Court’s 1964 decision in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, upholding Title II of the Act on the basis of Congress’ Commerce Clause power, his statement fails to mention the widespread attempts of southern cities and places of public accommodations to resist compliance with the Act, and the uneven response of the Fifth Circuit and United States Supreme Court in cases such as Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc. and Palmer v. Thompson. Indeed, southern resistance challenged the Department of Justice and the federal judiciary to determine legislative intent and southern motive in refusing to desegregate places of public accommodation even after the Act became law. And, in suggesting that the Act itself brought about the desegregation of all state services and facilities, he fails to note that such actions were the result of long court battles in cases like United States v. Paradise, in which Judge Myron Thompson, who took over the case from Judge Frank Johnson, Jr., confronted a Reagan administration Justice Department that opposed affirmative remedies mandating the hiring and promotion of black officers by the Alabama Department of Public Safety. Judge Thompson’s implementation of temporary race‐conscious measures to remedy the effects of the Department’s refusal to promote black officers was affirmed 5‐4 by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1986. See J. Bass, Taming the Storm, Chapter 26. Professor Loevy’s discussion of the immediate impact of the Act concludes with a brief commentary on the events surrounding the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights march, and President Johnson’s eventual proposal of voting rights legislation which would allow include “triggering provisions” in areas (of the south) where fewer than 50% of adults eligible to vote were actually voting. The provisions of the new Voting Rights Act would allow federal “examiners” to intervene in the election process administered by local voting registrars and other local election officials to insure that racial minorities were not denied the right to register to vote. Finally, Professor Loevy mentions the 1968 Housing Rights Act, passed largely because of the efforts of Clarence Mitchell, Washington Director of the N.A.A.C.P., and Senator Dirksen (and later strengthened by the Fair Housing Amendments of 1988), as the last of “the three great civil rights acts of the 1960’s to be enacted by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by the president.” Chronology • February 28, 1963: President Kennedy sends a “Special Message” on Civil Rights to Congress with additional proposals for voting rights laws; • June 19, 1963: Kennedy sends a “strengthened” bill to Congress, guaranteeing black citizens access to public accommodations, and permitting the federal government to file lawsuits to enforce desegregation; • May 8 – August 2, 1963: The House Judiciary Subcommittee (under the leadership of Rep. Emanuel Cellar of New York) reports out an even stronger bill which the President believes cannot secure passage; • August 28, 1963: 250,000 people participate in the famous “March on Washington”; • October, 1963: Robert Kennedy appears before the House Judiciary Committee asking for a more moderate bill, and a new version is adopted by the Committee; • November 20, 1963: The new version of the bill is reported out and 2 days later, President Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas; • January 30, 1064: The House Rules Committee votes out the civil rights bill and the House begins debate on January 31; • February 10, 1964: The House passes the bill by a vote of 290‐130; • February 26, 1964: The House bill is sent directly to the Senate, bypassing the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by James O. Eastland of Mississippi, an outspoken opponent of the bill; • March 9, 1964: Debate begins in the Senate, and southern opponents of the bill immediately launch a 16 day filibuster, attempting to send the bill back to Eastland’s committee; • March 30, 1964: Formal Senate debate of the bill begins, and southern opponents launch a second filibuster, which lasts until June 10, when the Senate votes 71‐29 for cloture; • June 19, 1964: The bill is sent back to the House, where a bipartisan coalition succeeds in blocking an attempted filibuster, and the bill proceeds to the House floor; • July 2, 1964: The House approves the bill by a vote of 289‐126 and it is signed into law by President Johnson as The Civil Rights Act of 1964. At the time of this book, Professor Robert Loevy was a Professor of Political Science at Colorado College. He is a recognized expert in minority rights and the electoral process. Joseph Rauh was, to many, a heroic figure in national Democratic Party politics, especially because of his masterful conduct of the hearings on the subject of the seating of minority delegates at the Party’s national convention in Atlantic City in 1964. Mr. Rauh was instrumental in Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 proposal of a federal Fair Employment Practices Committee (on the issue of racial discrimination which had been raised by A. Phillip Randolph), and he also led the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. Joseph Rauh is viewed as the principal leader of the lobbying efforts on behalf of the civil rights bill that eventually became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A civil rights visionary in the Democratic Party as early as 1948, Hubert Humphrey’s leadership in the Senate of the United States, and in the effort to secure the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, became nationally noteworthy in 1961, and he became the Democratic floor leader for the bill – defeating the southern filibuster and securing the bill’s passage in the Senate. John Stewart was the chief legislative assistant to Senator Humphrey. His commentaries on the legislation begin in April, 1964, and they are described by Professor Loevy as “the best first‐person” account available of the mammoth problems that faced those members of the U.S. Senate who were trying to enact a civil rights bill in the spring of 1964.”