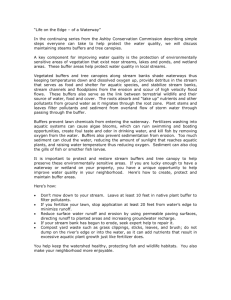

Conservation Buffers Planning and Design Principles

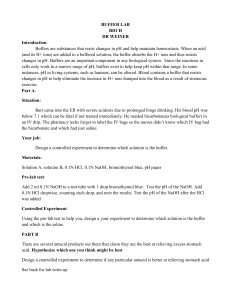

advertisement