Maximizing Energy Revenues - Providing the Best ... to the Contract Operator

advertisement

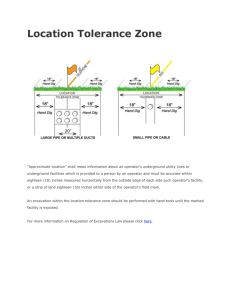

14th North American Waste to Energy Conference May 1-3, 2006, Tampa, Florida USA NAWTEC14-3184 Maximizing Energy Revenues - Providing the Best Incentive to the Contract Operator Anthony LoRe, P.E., DEE, Principal Camp Dresser & McKee Inc. 50 Hampshire Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Paul Stoller, Vice President Camp Dresser & McKee Inc. 50 Hampshire Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Robert Hauser, P.E., Operations Manager Pinellas County Utilities Department of Solid Waste Operations b 3095 - 114t Avenue North St. Petersburg, Florida 33716 retained by the community. This paper analyzes ABSTRACT several different approaches to sharing energy Communities that own waste-to-energy (WTE) by their facility to help pay for the costs to revenues in light of the operational experience gained over the past 20 plus years and concludes that, while energy revenue sharing is still in the facilities rely heavily on the revenues generated finance, operate and maintain these facilities. best interest of the community, the widely The two primary revenue streams are tipping employed strategy of a 9011 0 split may not offer fees and energy sales, generally in the form of the best incentive, and therefore may not lead to electricity. While communities often retain all of the maximization of energy revenues to the the tipping fee revenue, revenue from the sale of community. energy is nearly always shared with the contract operator. In some cases the shared energy INTRODUCTION revenues include both capacity and electricity payments. The basis of this strategy is to offer As of 2004, there were 89 WTE facilities the contract operator an added incentive to operating in the United States [1]. Most of these maximize this revenue stream through more projects were developed in the 1980s and early efficient operation and, in the case of capacity payments, to meet certain capacity commitment 1990s and are approaching 20 years of operation. More than one-third of the WTE facilities are criteria required by the energy purchaser. This publicly owned, with the vast majority of these strategy recognizes that the contract operator has plants being operated and maintained by private some degree of control over the factors that affect energy production. firms under 20 or 25 five year service agreements. The contract operator's Under most existing service agreements, which annual service fee or a processing fee for each compensation typically consists of either an date back to the 1980s, energy revenues are ton of waste processed and, in many cases, a shared on a 90110 basis, with 90 percent going to share of revenues from the sale of energy and the community. Now that many of these service metals recovered from the waste and/or ash agreements are coming up for renewal or are streams. expiring, communities will need to revisit how best to share energy revenues with the contract Most of the original service agreements for operator in order to maximize the total revenues publicly owned facilities will be coming up for 47 Copyright © 2006 by ASME renewal or will be expiring within the next 5 years, which will require these communities to municipality receives 100 percent of the net electricity revenues up to an armual guarantee with the contract operator receiving significantly negotiate new service agreements either with the current operator on a sole-source basis or as part more than 10 percent of the revenues from of a request for proposal process. This presents an opportunity for the community to review the electricity generated in excess of an annual guarantee. terms and conditions of the original service agreement in light of the operational experience OPERATING EXPERIENCE WITH 10 PERCENT ENERGY REVENUE SHARE gained over the first term including the merits of sharing a portion of the energy revenues with the contract operator. Energy revenues have A 10 percent energy revenue share has, for the historically been a significant source of most part, been adopted as the generally additional revenue to the contract operator, representing as much as 10-15 percent of their total revenues. accepted industry standard over the years. However, actual experience over the past 20 years suggests that this approach does not offer enough incentive for the contract operator to optimize energy production. For example, the PAST ENERGY REVENUE SHARING PRACTICES contract operator is less likely to undertake maintenance and repairs to increase or maintain Energy sales are also a significant source of performance if his share of the incremental revenue is not significantly higher than his cost revenue to the community and are critical to achieving a competitive tipping fee. Total energy revenues can be equivalent to $20-$40 to undertake the work. Consequently, the community often realizes little return for sharing per ton of waste depending on the energy this portion of the revenue stream. The contract contract price. Therefore, maximizing energy operator, meanwhile, often has to expend little or production should be one of the community's no effort to realize this revenue and may, in fact, primary operational goals. There are a number reduce expenses by calculating the economic tradeoffs of the potential savings on maintenance of ways to maximize energy revenues including: expenses versus the potential loss of incremental (i) generating more electricity by increasing facility throughput energy revenues. through higher steam capacity Typical maintenance and repair work that can be susceptible to such economic trade-off analyses as a result of this revenue sharing approach utilization and/or higher boiler availability; include, for example, the cleaning frequency of (ii) (iii) generating more electricity by optimizing the efficiency of the steam condensing systems (e.g., surface power cycle; and/or condensers) and the replacement of failed condenser tubes, which are generally capped selling a higher percentage of the gross electricity produced by instead. Deferring this work can end up reducing the efficiency of the power cycle and result in reducing in-plant power consumption. lower energy production. However, if the reduction in the contract operator's share of the condensers, cooling towers, air cooled electric revenues is less than the savings that the Since the contract operator has a large degree of contract operator realizes by deferring control over all of the above factors, consideration is often given to sharing a portion maintenance, then the contract operator is economically incentivized to defer the work and of the net energy revenues with the contract operator as a fmancial incentive to maximize of the deferred maintenance is born by the reap the economic benefit. Most of the downside contract community under a 90/10 energy revenue sharing approach. these revenues. In fact, most of the original WTE service agreements provided for sharing a portion of the net electricity revenues with the contract operator. In the vast majority of these To illustrate this point, consider the cleaning deals, the municipality receives 90 percent of the frequency for an air cooled condenser. Cleaning total net electricity revenues and the contract an air cooled condenser every other month operator 10 percent. In a few cases, the during the summer months has been observed to Copyright © 2006 by ASME 48 3 result in a one-half inch mercury absolute (0.50 Option in HgA) increase in the condenser pressure during the months between cleanings, which Energy Revenues - Percentage Share ofExcess Net lowers the steam turbine-generator output by Under this option, the community would share a approximately 1.5 percent. For a30 MW turbine-generator, this results in a decreased output of324 MWH per month or $16,200 in fixed percentage (e.g., 50 percent) of the net energy revenues from electricity generated in excess of an annual amount stated in the service lost energy revenues based on an energy rate of agreement. $0.05/kwh. The community's share of the lost energy revenues would be $14,580 during each Option 4 of these months while the contract operator's lost Factor - Energy Credit Based on an Efficiency revenues would only be $1,620. In this case, the contract operator would be unlikely to clean the air cooled condenser monthly since his cleaning Under this option, the community would pay an energy credit to the contract operator for costs would most likely exceed his potential operating in excess of a base efficiency factor additional revenues. However, if the revenue (e.g., KWH/ton waste processed, KWHIKlbs share for excess energy was 50/50, for example, steam). the contract operator's return would likely justifY the additional expense for monthly cleaning and CONCLUSION the community's total energy revenues would also increase. In order to maximize energy revenues, it would Additionally, the traditional 90/10 energy be in a community's best interest to share energy revenues with the contract operator. However, revenues split also does not generally provide based on operating experience over the past 20 sufficient incentive for the contract operator to reduce in-plant power consumption through years, the widely employed strategy of a 90/10 split may not offer the best incentive. operational and/or process changes such as increasing the efficiency of in-plant electrical While payment of an energy credit based on an efficiency factor would tie energy revenue loads. In-plant power consumption represents a significant portion of the gross power generated, sharing directly to the efficiency of the power typically 12-15 percent on large WTE facilities cycle, efficiency factors can be affected by and up to 20 percent on smaller facilities. conditions outside the control of the contract operator and therefore would not be as fair an ENERGY REVENUE SHARING OPTIONS approach. There are several potential energy revenue sharing options that are available to a community Sharing energy revenues based on excess net revenues (Option3) would appear to be the best that will need to enter into a new service agreement in the future including the traditional approach because it offers the greatest incentive to the contract operator to maximize energy 90/10 split. The following four options represent revenues, particularly if the contract operator's revenue share of the excess net revenues is 50 a range of different approaches, each with its own merits. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of each option is provided in percent or higher. Under this option, the contract operator would only share in energy revenues Table 1. that were realized by exceeding a predetermined annual electricity generation guarantee. This Option 1 - No Energy Revenue Sharing approach ensures that the community receives a minimum amount of energy revenues before the Under this option, 100 percent of the energy contract operator is eligible for compensation revenues would be retained by the community. and rewards the contract operator solely for exceeding a minimum threshold. The contract Option 2 - Percentage Share of Total Net operator would be more likely to undertake Energy Revenues additional maintenance and repairs to maximize Under this option, the community would share a investment would be much greater. We have fixed percentage (e.g., 10 percent) of the total net proposed this approach in the draft service energy revenues with the contract operator. agreement that was sent to the three prequalified performance because the potential return on his 49 Copyright © 2006 by ASME contract operators in February 2006 for the Reprocurement of a contract operator for the Pinellas County 3,000 tpd WTE facility. We may have some additional information to report at the conference regarding the wisdom and viability of this approach from the contract operator's perspective. REFERENCES [1] Kiser, J.V. and Zannes, M., "The 2004 IWSA Directory of Waste-To-Energy Plants", Published by the Integrated Waste Services Association, Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2006 by ASME 50 � en ;l> � N o o 0\ @ <g. (") o '0 '< :J. Ul 4 3 2 I - - - - Option directly to the efficiency of the Efficiency Factor May result in a higher service fee since this lower revenue stream would offset less of the contract operator's costs and expected profit Community would likely retain operator (e.g., refuse heating value, ambient air temperature, etc.) more of the total energy revenues processing fee service fee was based on a per ton under agreements where the twice for increased throughput reward the contract operator power cycle and would not Ties energy revenue sharing Energy Credit Based on Efficiency factors can be affected by conditions outside the control of the contract throughput, the later of which the contract operator would also be rewarded if the service fee was based on a per ton processing fee Relatively easy to administer Rewards contract operator for both higher power cycle efficiency and increased Community would likely retain surpass the stated energy production amount Excess Net Energy Revenues May result in a higher service fee since this revenue stream may offset less of the contract operator's costs and expected profit service fee was based on a per ton processing fee throughput, the later of which the contract operator would also be rewarded if the more of the total energy revenues Offers greatest incentive to expected profit contract operator's costs and Rewards contract operator for both higher power cycle efficiency and increased to increase other revenues revenue stream to help offset the Community retains less than the total energy revenues, thereby causing the community by providing an alternative Minor incentive to maximize electricity generation May result in lowest service fee Relatively easy to administer not be available to help offset the contract operator's costs and expected profit Would likely result in higher service fee since a portion of this revenue stream would revenues No administrative effort Disadvantage Lack of incentive could lead to lower energy revenues for the community Advantage Community retains 100% of Percentage Share Based on Total Net Energy Revenues Percentage Share Based on No Energy Revenue Sharing Table 1 Comparison of Energy Revenue Sharing Options