ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

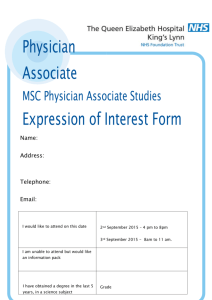

advertisement