Document 10298247

advertisement

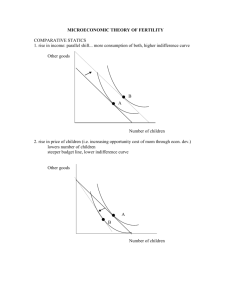

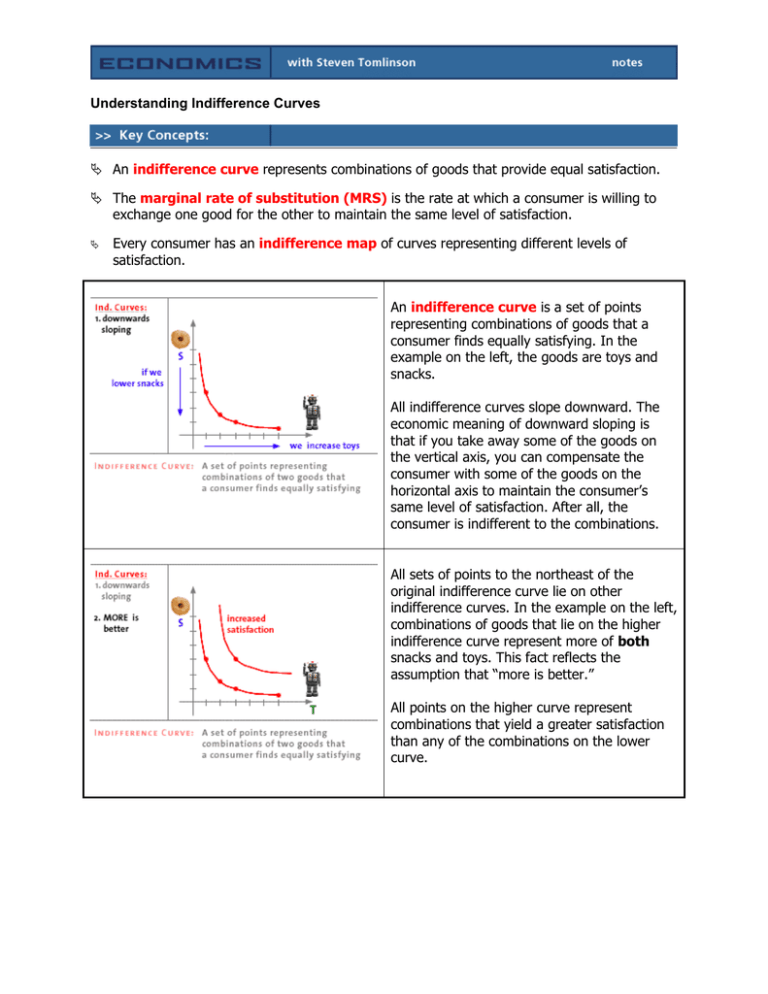

Understanding Indifference Curves An indifference curve represents combinations of goods that provide equal satisfaction. The marginal rate of substitution (MRS) is the rate at which a consumer is willing to exchange one good for the other to maintain the same level of satisfaction. Every consumer has an indifference map of curves representing different levels of satisfaction. An indifference curve is a set of points representing combinations of goods that a consumer finds equally satisfying. In the example on the left, the goods are toys and snacks. All indifference curves slope downward. The economic meaning of downward sloping is that if you take away some of the goods on the vertical axis, you can compensate the consumer with some of the goods on the horizontal axis to maintain the consumer’s same level of satisfaction. After all, the consumer is indifferent to the combinations. All sets of points to the northeast of the original indifference curve lie on other indifference curves. In the example on the left, combinations of goods that lie on the higher indifference curve represent more of both snacks and toys. This fact reflects the assumption that “more is better.” All points on the higher curve represent combinations that yield a greater satisfaction than any of the combinations on the lower curve. Recall from algebra or from the previous lectures on graphing that the slope of a curve at any point is the slope of a tangent line at that point. An indifference curve is convex, meaning that the slope decreases as you go down it. The economic interpretation of the slope is called the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) or the rate at which the consumer is willing to trade one good for another. The MRS is large near the top of the curve. This means that at the top, this consumer has a lot of snacks and not many toys. To maintain the same satisfaction, he is willing to give up many snacks and be compensated with just a few toys. At the lower end of the indifference curve, this consumer has a small MRS. He has a lot of toys but few snacks. To maintain his satisfaction, if he gives up one snack, he will have to be compensated with a lot of toys. Conversely, if he gives up one toy, you will not have to compensate him with many snacks. Each consumer has an indifference map of indifference curves in the goods space. Each indifference curve represents different levels of satisfaction. Because of the principle of “more is better,” you can say that the higher ones are preferred to the lower ones. Indifference curves do not indicate specific amounts of satisfaction. They are ordinal, meaning that one is preferred over another. The final property of indifference curves is that indifference curves can never cross. Consider a case where indifference curves do cross at point b: D is preferred to A, and C is preferred to E because D and E are on a higher curve. But if they cross, then A = B = C. Thus, A is preferred to E, and in that case, E = B = D. This result tells us that A is now preferred to D, which contradicts the original statement.