Big Bad Banks?

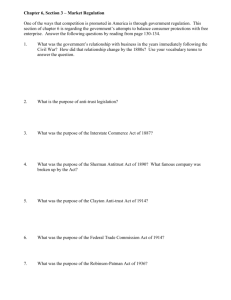

advertisement