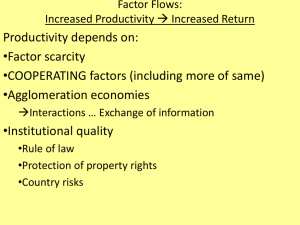

Knowledge Flows in Local Context 1 2 3

advertisement