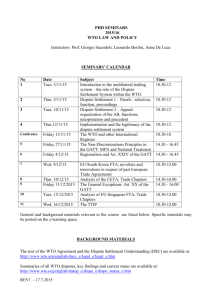

Forum Choice in Trade Disputes:

advertisement