Recent Transitions Affecting Private Pension Plans in the

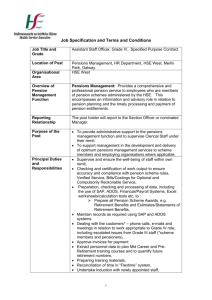

advertisement