Werner Karl Heisenberg (December 5, 1901 – February 1, 1976) Biography

advertisement

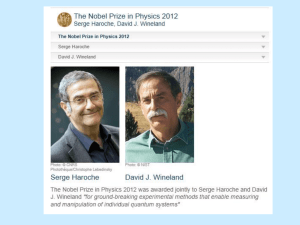

Werner Karl Heisenberg (December 5, 1901 – February 1, 1976) Biography By Charles Wood Werner Karl Heisenberg was born on December 5, 1901, in Wurzburg, Germany. He was the second child of August and Anna Wecklein Heisenberg. His father taught Greek philology at the University of Wurzburg and ancient languages at the secondary school Altes Gymnasium. In 1910, August moved his family to Munich, where he had been appointed to a professorship at the University of Munich. Heisenberg attended primary school in Wurzberg and Munich. He began piano lessons at an early age, and by the age of thirteen, he was an accomplished musician. Heisenberg remained an avid player throughout his life. In April of 1937, Heisenberg married Elisabeth Schumacher, who was the daughter of the noted Berlin professor of economics, Hermann Schumacher (Cassidy 394). They had seven children - four daughters and three sons (Notable Scientists). In 1911, Heisenberg enrolled in the Maximilians-Gymnasium, where his grandfather was headmaster. Before he graduated secondary school, Heisenberg taught himself calculus and wrote a paper on number theory (Cassidy 394). However, in the summer of 1918, his education was interrupted by the heavy onset of World War I. During this time, he was called to help the wartime effort by harvesting crops in Bavarian fields (Notable Scientists). Afterward, he returned to Munich and, in 1920, applied to the University with the intension of studying mathematics. After Ferdinand von Lindemann, professor of mathematics, refused his application, Heisenberg took the advice of his father and applied for his second choice, physics. With his father’s help, Heisenberg arranged an interview with the professor of theoretical physics, Arnold Sommerfeld, who agreed to admit him to his seminar (Cassidy 394). 2 While studying under Sommerfeld, Heisenberg became acquainted with a fellow student Wolfgang Pauli and began working with the details of the Zeeman effect. The Zeeman effect is the enigmatic splitting of atomic spectral lines into more than the expected three components in a magnetic field. During his first semester, Heisenberg offered a model for the Zeeman effect that explained all of the known data in terms of the union between valence electrons and the remaining “core” electrons. In 1922, Heisenberg published his first paper explaining his model. This model violated many of the basic principles of quantum theory, as well as classical mechanics. Nonetheless, his model served as the basis for most future work with the Zeeman effect (Cassidy 395). Heisenberg obtained his doctorate under Sommerfeld in 1923. Heisenberg’s dissertation involved an inexact solution to the complex equations that are influential to the onset of hydrodynamic turbulence. Due to his primary interest in theoretical quantum physics, Heisenberg spent little time in the laboratory on experimentation. As a consequence, he was unable to answer certain questions proposed during his oral examination by Wilhelm Wien, the professor of experimental physics. Due to Heisenberg’s incompetence, Wien recommended that Heisenberg should not pass. However, due in part to Sommerfeld’s negotiation, Wien was overruled, and Heisenberg received his degree (Notable Scientists). In June 1922, Sommerfeld took his students to Gottingen for a series of lectures on quantum physics to be presented by Niels Bohr. Heisenberg made a daring criticism of one of Bohr’s assumptions, leading to a confrontational discussion about the core model. As a result, Heisenberg and Bohr developed a mutual admiration and the beginning of a life long partnership. Shortly there after, Sommerfeld departed to visit the 3 University of Wisconsin. He left Heisenberg in Gottingen under the direction of Max Born. Born was later impressed by Heisenberg’s lecture on the core model. As a result, Born arranged a private assistantship for Heisenberg under his direction. With the exceptions of a semester-long visit to Munich and another semester spent working under Bohr in Copenhagen, Heisenberg remained in Gottingen until May 1926 (Cassidy 396). In June 1925 during a battle with hay fever on the island of Heligoland, Heisenberg devised a new method for calculating the energy levels of “atomic oscillators” (World Biography). Heisenberg departed from Bohr’s idea of indistinguishable particles moving in unseen, predetermined paths. Instead, he concentrated on a theory that expressed the physical unknowns in atomic systems as abstract arrays of numbers, or matrices. After his return from Heligoland, he collaborated with Bohr and Pascual Jordan, and together they published The Physical Principles of Quantum Theory, which detailed these new matrix mechanics. In 1925, Heisenberg also published About the Quantum-Theoretical Reinterpretation of Kinetic and Mechanical Relationships, where he redefined Bohr’s model of the planetary atom and, as a result, significantly aided in the development of quantum mechanics (World of Mathematics). In May 1926, Heisenberg left Gottingen and accepted a position as Bohr’s assistant in Copenhagen. In February 1927, Heisenberg was studying the principles of an electron’s orbit about the nucleus. During this study, he imagined using a gamma-ray microscope to examine an electron’s motion. Heisenberg realized that measuring an electron’s properties using gamma rays would disturb the electron’s orbit. This in turn would alter its behavior, and the electron would objectively be lost. This lead Heisenberg 4 to the formulation of his principle of uncertainty, or indeterminacy - the contribution for which Heisenberg is best known (Notable Scientists). The uncertainty principle states that the precise simultaneous measurement of conjugate variables, such as the position and the momentum or the energy and the time of a particle, are excluded in principle. Hence, reciprocal relationships exist between the indeterminacies in the measurements of position (∆q) and momentum (∆p) or energy (∆E) and time (∆t). These can be represented by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, ∆p * ∆q ≅ h ∆E * ∆t ≅ h where h is Planck’s constant. In particular, Heisenberg stated that conventional notions of causality are undermined by the indeterminacy formula, since all initial conditions of a particle cannot be known (Cassidy 397). For the development of the uncertainty principle, as well as his other contributions to theoretical physics, Heisenberg was awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 1932 (Notable Scientists). In October 1927, Heisenberg was offered positions at the universities of Leipzig and Zurich. He chose the position at Leipzig and, as a result, became the youngest professor in Germany (Notable Scientists). While there, he published On the Perceptual Content of Quantum Theoretical Kinematics and Mechanics, which outlined his famed uncertainty principle (World of Mathematics). Heisenberg’s duties at Leipzig involved teaching a full schedule of classes, as well as administrative duties. As a result, his scientific output diminished. Nonetheless, his interest in theoretical physics led him to pursue research in many directions, including ferromagnetism, quantum electrodynamics, cosmic radiation, and nuclear physics (Notable Scientists). 5 Heisenberg’s position became especially fragile in the years prior to World War II, since the Nazis considered theoretical physics a “Jewish” science. Most of Germany’s scientists fled the country to take up residence in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other free nations. Heisenberg was one of the few world-class scientists who remained behind to protect Germany’s scientific traditions and institutions. In 1935, Heisenberg received an invitation to succeed his former teacher Sommerfeld in Munich. However, this honor was met with hostility from German political leaders, who branded Heisenberg as a “white Jew.” With his personal safety at risk, Heisenberg could not accept this position (Notable Scientists). At the beginning of World War II in 1939, Heisenberg moved to Berlin. He was appointed to “the uranium club” to develop the nuclear-fission atomic bomb. This project would consume the next five and a half years of his life (Notable Scientists). While he was involved with this project, Heisenberg was chosen as the professor of theoretical physics at the University of Berlin and as the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (World of Mathematics). When the war came to an end in 1945, Heisenberg and his bomb research team were captured and sent to England for a sixmonth internment period. Afterward, he returned to Gottingen and re-established the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, renaming it the Max Planck Institute of Physics, in honor of his colleague (Notable Scientists). Heisenberg did much to reorganize scientific research in the post-war years. As head of the Max Planck Institute and of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Heisenberg vigorously turned his attention to the formulation of a “unified theory of fundamental particles,” which stressed the role of symmetry principles. This theory 6 attempted to link all physical fields, such as gravitation and electromagnetism (Notable Scientists). In 1958, Heisenberg accepted a position at the University of Munich as professor of physics. While there, he published Introduction to the Unified Field Theory of Elementary Particles (1966). Previously, in 1955–56, Heisenberg had presented his Gifford Lectures at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. These lectures were later printed under the title Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science (World Biography). Heisenberg retired in 1970 but continued to write on various topics. He published an autobiography, Physics and Beyond (1971), and several books dealing with philosophical and cultural implications of atomic and nuclear physics (World Biography). However, his health began to deteriorate in 1973 (Notable Scientists). Overwhelmed by kidney and gall bladder cancers, he passed away in 1976 at the age of seventy-five (World of Mathematics). He was survived by his wife and their seven children (Notable Scientists). 7 Works Cited Cassidy, David A. “Heisenberg, Werner Karl.” Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Eds. Lesson H. Adams and Fritz H. Laves. 1990. “Werner Karl Heisenberg.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2nd ed. 17 vols. Gale Research, 1998. Biography Resource Center. Online. 11 Feb. 2003. <http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC> “Werner Karl Heisenberg.” Notable Scientists: From 1900 to the Present. Gale Group, 2001. Biography Resource Center. Online. 11 Feb. 2003. <http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC> “Werner Karl Heisenberg.” World of Mathematics. 2 vols. Gale Group, 2001. Biography Resource Center. Online. 11 Feb. 2003. <http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC> 8