Monopolistic Competition

advertisement

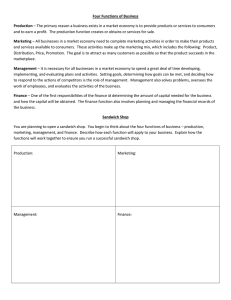

Monopolistic Competition It is wrong to assume that competition is good and monopoly power is bad. The reality is much more complex than this as we shall see when we analyse and evaluate imperfectly competitive markets where existing firms have genuine market power in setting prices for consumers. However there does appear to be a consensus that increasing the amount of competition in a market can bring about positive side-effects not only for consumers but also for society as a whole. In this section we consider briefly some of the effects of competition within a market – and we return to it when we consider the nature and consequences of contestable markets. Adam Smith on Competition “The natural price or the price of free competition ... is the lowest which can be taken. [It] is the lowest which the sellers can commonly afford to take, and at the same time continue their business.” Adam Smith, the Wealth of Nations (1776), Book I, Note VII The common characteristics of markets that are considered to be “competitive” are: • • • • • Lower prices because of the large number of competing firms. Suppliers face elastic demand curves and any rise in price will lead to a fall in demand and in total revenue. The cross-price elasticity of demand for one product with respect to a change in the price of another will be high suggesting that consumers are prepared to switch their demand to the most competitively priced products in the market-place. Low barriers to entry – new firms will find it relatively easy to enter markets if they feel there is abnormal profit to be made. The entry of new firms provides competition and ensures prices are kept low in the long run. Lower total profits and lower profit margins than in markets which dominated by a few firms. Greater entrepreneurial activity – the Austrian school of economics argues that true competition is a process rather than a static condition. For competition to be improved and sustained there needs to be a genuine desire on behalf of entrepreneurs to engage in competitive behaviour, to innovate and to invent to drive markets forward and create what Joseph Schumpeter famously called the “gales of creative destruction”. Economic efficiency – competition will ensure that firms attempt to minimise their costs and move towards productive efficiency. The threat of competition should lead to a faster rate of technological diffusion, as firms have to be particularly responsive to the changing needs of consumers. This is known as dynamic efficiency. The UK government has a firm commitment to competition as part of its competition policy agenda. In a detailed research document on the static and dynamic gains from increasing the contestability of UK markets publishes in 2004, the Department for Trade and Industry came out firmly in favour of a procompetition policy regime. This short quote provides a flavour of their arguments. The gains from greater competition “Competition is a process, in which the long-run and short-run may look very different, and in which firms use a variety of weapons – not just price – with which to compete. Innovation, product design and variety are often important parts of the competitive game between firms” Source: DTI report on competition in UK markets, July 2004 The importance of non-price competition In competitive markets which are not perfectly competitive, frequently it is the effectiveness of non-price competition which is crucial in winning sales and protecting or enhancing market share. Panini Peddlers, Baps, Baguettes and Bagels - Product Differentiation in the Sandwich Market According to the British sandwich industry, approximately 1.8 billion sandwiches are purchased outside the home each year and the retail sandwich market is worth approximately £3.5 billion, over three times the IB Economics notes Monopolistic competition Neil.elrick@tes.tp.edu.tw value of the pizza market for example. About a million consumers buy sandwiches five days a week. The industry employs over 300,000 people and if the latest consumer profiles are to be believed, the most likely person in front of you in the queue for a bap, wrap or baguette is likely to be male, between 25-44 years old and also in a rush – our average lunch break is now less than thirty minutes! From our largest supermarkets to the smallest corner shop; from dedicated sandwich makers who deliver direct to offices to coffee shops and independent sandwich bars, from petrol stations to pubs and local and national chains of bakers, the many competing suppliers in the industry are fighting a daily battle for sales, revenue and market share. Differentiating the product Here are some of the ways in which the humble sandwich can be made distinct against its competitors in the market-place: • Hot and cold sandwiches • Different styles – e.g. a bap, baguette, wraps and filled bagels • Speciality breads such as focaccia and ciabatta • Product range - including • Organic ingredients • Healthy options (e.g. non-mayo) • Packaging and branding • Quality of ingredients • Different fillings • Made to order in the store / off the shelf / home or work delivery of sandwiches • Finest range / value sandwiches Price matters in the market but not perhaps to the degree that people expect. According to research from food analysts Winship, “UK sandwich consumers are not always driven by price and they are more concerned with perceived value for money and will pay more for a product they believe delivers that rather than shop around for cheaper offerings.” IB Economics notes Monopolistic competition Neil.elrick@tes.tp.edu.tw