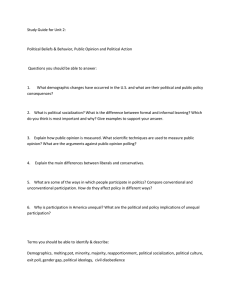

Chapter 9 Content overview

advertisement

Chapter 9 Campaigns and Voting Behavior Chapter Overview Elections form the foundation of the American system of democracy. They are the means by which citizens select the leaders of the government who, presumably, enact policies on behalf of constituents. But Americans often have a weak understanding of how campaigns, elections, and voting in the United States actually function, despite their importance. In this chapter, we explore the process of seeking elected office in the United States. We begin by exploring the fundamental election procedures—the rules of the game—that define how candidates are nominated and how winners are determined in American elections. We focus in particular on the fairness of our current system. Then we examine the key objectives of political campaigns and outline the benefits of incumbency and the role of money in the campaign process. Next, we consider the factors that influence the decisions of voters, focusing in particular on the role of party identification, candidate evaluation, and policy options on voting. We conclude by evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of the U.S. system of campaigns and elections. By the end of the chapter, students should have a good command of the formal structures and functions, as well as the behind-thescenes politics, of campaigns and elections in the United States. Lecture Notes 9.1 Evaluate the fairness of our current system of presidential primaries and caucuses. LECTURE 1: Examine the importance of the invisible primary with your students. The “invisible primary” refers to the period between which a candidate announces an intention to run for a particular office and the time at which the actual primaries take place. During the invisible primary, candidates are seeking to accomplish two things: First, they want to raise money and lay the infrastructure for their campaign, recruiting volunteers, establishing field offices, and so on. The increasingly compressed time frame for the primary season makes this even more difficult, as candidates must focus on all of the competitive primaries rather than being able to focus on just a few states at a time as they could during a more spread out primary season. Second, they want to establish momentum for their candidacy, establishing themselves as a viable candidate in the eyes of the electorate and the media. In many primary seasons, the candidate who most successfully finishes the invisible primary handily wins the actual primary and the party’s nomination. LECTURE 2: Students often take the right of political participation for granted and may not always appreciate or understand the voting restrictions that jurisdictions have imposed. Lead an interesting lecture on this topic. At times, states have limited the right to vote in particular elections to persons who have a special interest or stake in the outcome. Such limitations on the franchise develop, ostensibly, from the perception that voters with an interest in the election would cast more fully considered ballots and that such voters should thus be accorded a greater voice in determining the election’s outcome. Although the Supreme Court has not declared such limitations on the right to vote unconstitutional per se, it has developed a test of constitutionality that few such restrictions can survive. Kramer v. Union Free School District (1969) constituted the Court’s first exploration of this issue. In the case, a childless bachelor who lived with his parents and thus neither owned nor leased property challenged a New York statute that limited the vote in certain school district elections to property owners or lessees and parents of children in the school district. The state attempted to justify the law by invoking the need to confine the franchise to the group that was “primarily interested in school affairs.” The state argued, among other things, that the issues involved were complex and that materials explaining these issues were sent home with the children; therefore, nonparents were less informed than parents. The Court, applying vigorous equal protection scrutiny, found the statute unconstitutional because it was not carefully tailored to affect that interest. The statute, said the Court, included many persons who have only a remote and indirect interest in school affairs and excluded others who have a distinct and direct interest in school affairs. The dissenting judges said that the state had the right to limit those who could vote in the manner it did and that if this person was entitled to vote, then the same argument could be made by any other person who expressed an interest in voting but would not normally be allowed to vote in school district elections, such as minors and those living in another state. In other similar cases, the Supreme Court has ruled in the following manner: Overturned a statute permitting only real property owners to vote on a bond issue Overturned a state statute that included a durational residency requirement Upheld a state statute denying convicted felons the right to vote Upheld statutes allowing only real property owners to vote in “water storage district” elections Upheld a state statute denying those awaiting trial in jail the right to vote by absentee ballot. LECTURE 3: In a primary election, voters decide which candidate will represent the party in the general election. Differentiate between competing types of primaries used in the United States. In closed primaries, only registered members of the party are allowed to vote. For example, only registered Republicans are permitted to vote for the Republican candidate, and only registered Democrats are permitted to vote for the Democratic candidate. Closed primaries allow the party maximum control and promote party strength. In open primaries, anyone is permitted to vote regardless of party affiliation. Republicans and independents are allowed to vote in the selection of the Democratic nominee and vice versa. Open primaries are considered more democratic since participation is open to all voters, regardless of party affiliation Blanket primaries are similar to open primaries, except that voters may choose to vote in either party’s primary, but not both, on an office-by-office basis. The central difference is that in an open primary, a voter must select a single party in whose primary election he or she will participate. In a blanket primary, by contrast, a voter might participate in the Republican primary for president, the Democratic primary for governor, and so on. In a runoff primary, the two candidates with the most votes stand in the general election, regardless of party. A runoff primary could result in a general election in which two members of the same political party compete against one another for the office. LECTURE 4: Explain the changes to the presidential nominating process since 1972. The process for selecting nominees for president is not governed by the U.S. Constitution but has developed instead through the practices of states and political parties. Prior to 1972, the state delegations responsible for nominating a party’s candidate for president were chosen by party leaders. This change was facilitated by the chaos at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, where Hubert Humphrey secured the party’s nomination despite strong support for Eugene McCarthy. Following the 1968 fiasco, the McGovern-Fraser Commission, sponsored by the Democratic National Committee, recommended reforms to the nomination process to introduce greater transparency. The Republican Party adopted similar reforms. Today, the vast majority of delegates to the national party conventions are selected by the voters, either through caucuses or primary elections. In general, these delegates are pledged to vote for a particular candidate. Caucuses are meetings of the party in which participants select a candidate for office. Iowa, Texas, and Nevada all use party caucuses to decide their presidential nominees. Primary elections are votes, usually by the party members, to select a candidate to represent the party in the general election. Primaries can be open or closed. Most states use primary elections to select their presidential nominee. Still, a handful of delegates are appointed by the party at either the national or state level. These delegates, often referred to as “superdelegates,” are members of Congress, governors, and other distinguished party members. They are not promised to a particular candidate and are free to vote for any candidate they choose. In most years, superdelegates are not important, as the party is generally unified behind a single candidate by the time the party convention takes place. In the 2008 election, though, it looked like the competition for the Democratic nomination—between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama—might come down to the decision of a small number of superdelegates. LECTURE 5: Differentiate between the processes used in the Democratic and Republican party primaries. The Democratic Party allocates delegates through primary elections on a proportional basis. Thus, if a candidate receives 40 percent of the popular vote in the primary election, he or she will receive 40 percent of the delegates from that state. Until 2012, the Republican Party allocated delegates through primary elections on a winner-take-all basis. Thus, no matter how narrow a candidate’s margin of victory, that candidate received all of that state’s delegates. This had the advantage of making elections more decisive and often meant that the Republican nominee was selected earlier than the Democratic nominee. Today, some Republican primaries are allocated on a proportional basis. While this makes it easier for candidates to accumulate delegates, it also stretches out the primary campaign season. In other states, Republican primaries have become more exclusive, with strict requirements for candidates to even make it onto the ballot. In Virginia, for example, candidacy requirements were so strict that only Mitt Romney and Ron Paul even made it onto the ballot. Other popular candidates—including Newt Gingrich, Rick Perry, Michele Bachman, and Rick Santorum—failed to qualify. 9.2 Explain the key objectives of any political campaign. LECTURE 1: Differentiate between the three stages of the presidential campaign process. Persons seeking to have a viable chance at winning the presidency must first secure the nomination of one of the two major political parties in the United States. Part of this process includes raising money and developing a campaign infrastructure that will carry the candidate through the nomination process and into the general election. This is often referred to as the invisible primary. During this first stage, candidates develop name recognition and campaign in primary elections and party caucuses to secure their party’s nomination. The party’s nominee is formally named at the national party convention, generally held in late summer of a presidential election year. The party conventions mark the formal launch of the presidential campaign season, with each party rallying behind their nominee. Party conventions generate excitement and energize the party base. In addition to formally nominating the party’s candidate for president and vice president, the party conventions also adopt the official party platform and provide plenty of opportunities for rising party stars and distinguished party veterans to address the party membership and the American electorate more generally. After the party convention comes the general election. During this period, candidates generally crisscross battleground states, seeking to lay out a path to secure the minimum 270 electoral votes necessary to win the presidency. Television and radio advertising usually play a more important role during the general election. Fundraising is also critical, as advertising, campaign staff, get-out-the-vote drives, and other campaign-related expenses mount. LECTURE 2: Running for president is a long and complex task, involving hundreds of paid campaign staff members (and often tens of thousands of unpaid volunteers) and costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Securing the party’s nomination is just the first step in this process. Examine the presidential campaign process with your students and outline the politics of presidential campaigns after party nomination. The presidential campaign finance system provides funds to match small individual contributions during the nomination phase of the campaign for candidates who agree to remain within spending limitations. Presidential hopefuls face a key dilemma. To get the Republican nomination, a candidate has to appeal to the more intensely conservative Republican partisans, those who vote in caucuses and primaries and actively support campaigns. Democratic hopefuls have to appeal to the liberal wing of their party as well as to minorities, union members, and environmental activists. But to win the general election, candidates have to win support from moderate and pragmatic voters, many of whom do not vote in the primaries. Selection of a vice presidential nominee usually garners a campaign considerable attention. Vice presidential candidates are often used to address a liability in the presidential campaign or to shore up support from a particular region or group. Televised presidential debates are a major feature of presidential elections. Since 1988, the nonpartisan Commission on Presidential Debates has sponsored and produced the presidential and vice presidential debates. Minor-party candidates often charge that those organizing debates are biased in favor of the two major parties. To be included in presidential debates, such candidates must have an average of 15 percent or higher in the five major polls the commission uses for this purpose. Presidential candidates communicate with voters in a general election and in many primary elections through the media: broadcast television, radio, cable television, and satellite radio. Candidates must also be legally eligible and on the ballot in enough states to be able to win at least 270 electoral votes. LECTURE 3: Examine the importance of selecting a theme or message for a political campaign, using key themes from historical campaigns. You may also find powerful commercials that illustrate some of these themes. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson campaigned on a platform arguing that his opponent, Barry Goldwater, was too unstable to defend the country and deal with the threat of communism in Southeast Asia. His “Daisy” ad (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExjDzDsgbww) remains one of the most powerful political commercials in campaign history. President Ronald Reagan chose to run a more upbeat campaign in 1980. His “Morning in America” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=EU-IBF8nwSY) commercial illustrates the hopefulness of his campaign. In 2012, President Barack Obama used a speech by Mitt Romney to paint him as out of touch with American voters: www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9xCCaseop4. An outstanding collection of ads is available at the Living Room Candidate website: www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials. LECTURE 4: Use video clips to illustrate the importance of strong communication skills in political leaders. President Ronald Reagan was known as the great communicator. Reagan’s 1980 campaign: “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” www.youtube.com/watch?v=loBe0WXtts8 Regan’s 1987 speech at the Brandenburg Gate: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtYdjbpBk6A Reagan’s 1989 farewell address. www.youtube.com/watch?v=qUGR5ushe0E President Bill Clinton was an effective orator, but he excelled in interpersonal communication, projecting a sense of connection with the average voter. His performance in the 1992 debate with George H. W. Bush illustrated this ability to connect: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ta_SFvgbrlY. His performance stood in contrast with that of President Bush: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ffbFvKlWqE. His response to the Oklahoma City bombing, perhaps most notably his “I feel your pain” (www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/bonusvideo/presidents-crisis-clinton)speech, also illustrates this skill. President Barack Obama evoked memories of historic figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Kennedy brothers (John and Robert). In 2004, Barack Obama, who was running for the U.S. Senate at the time, delivered the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. His “Red State, Blue State” speech (www.youtube.com/watch?v=eWynt87PaJ0) represented his oratory skills. Even more powerful was his “We Are One People” speech (www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_lQYC7vqBg)delivered after taking second place to Hillary Clinton in the New Hampshire primary. Screen video footage of their speeches and discuss the importance of strong oratory skills for elected leaders. LECTURE 5: Whether you supported or opposed the candidate, the 2008 Obama presidential campaign clearly rewrote the rulebook on political mobilization. Explore the ways in which the 2008 Obama campaign mobilized voters in support of their platform. The 2008 Obama campaign was the first presidential campaign to make extensive use of social media to connect directly to the voters. This had several important implications. It allowed the campaign to raise significant amounts of money by appealing directly to potential supporters in targeted ways. Because of this, the Obama campaign could target microgroups of supporters with individual messages. It also kept Obama’s supporters mobilized and energized. The campaign was able to send regular updates in the form of text messages, tweets, and e-mails to millions of supporters, maintaining a strong sense of community and engagement. The use of social media also facilitated greater engagement among young voters, who turned out in record numbers in support of Obama. The 2012 Obama campaign continued to make use of social media but also expanded into widespread use of data mining to reach potential supporters. 9.3 Outline how the financing of federal campaigns is regulated by campaign finance laws. LECTURE 1: The U.S. ideal that anyone—even a person of modest or little wealth—can run for public office and hope to win has become more of a myth than a reality. One reason for escalating costs is television. Organizing and running a campaign is expensive, limiting the field of challengers to those who have their own resources or are willing to spend more than a year raising money from interest groups and individuals. Unless something is done to help finance challengers, incumbents will continue to have the advantage in seeking reelection. The high cost of campaigns dampens competition by discouraging people from running for office. Potential challengers look at the fundraising advantages incumbents enjoy—the campaign war chests carried over from previous campaigns that can reach $1 million or more and the time it will take them to raise enough money to launch a minimal campaign—and they decide not to run. Moreover, unlike incumbents, whose salaries are being paid while they are campaigning and raising money, most challengers have to support themselves and their families throughout the campaign, which for a seat in Congress often lasts more than one year. For most House incumbents, campaign money comes from political action committees (PACs). PACs and individuals spend money on campaigns for many reasons. Most of them want certain laws to be passed or repealed, certain funds to be appropriated, or certain administrative decisions to be rendered. Campaign finance legislation cannot constitutionally restrict rich candidates—the Rockefellers, the Kennedys, the Perots, the Clintons, the Romneys—from spending heavily on their own campaigns. Big money can make a big difference, and wealthy candidates can afford to spend big money. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BRCA) included a millionaire’s provision that the Supreme Court later declared unconstitutional. The provision allowed candidates running against self-financed opponents to have higher contribution limits from individuals or parties contributing to their campaigns. Another development that has made individual donors more important is the Internet. Starting in 2000 with the McCain presidential campaign and then expanding with the Howard Dean candidacy for president in 2004, people started giving to candidates via the Internet. But it was the Obama campaign in 2008 that demonstrated the extraordinary power of the Internet as a means to reach donors and a way for people to contribute to a candidate. LECTURE 2: Explain the difference between hard money and soft money and examine the role of each in political campaigns. The 1976 and 1978 elections—the first after the Federal Election Campaign Act— saw less generic party activity and prompted parties to seek legislation allowing individuals or groups to avoid contribution limits if money was given to political parties for “party-building purposes,” such as voter registration drives or generic party advertising. This money came to be defined as soft money, in contrast to the limited and more-difficult-to-raise hard-money contributions to candidates and party committees committed to candidate-specific electoral activity. Banning soft money became the primary objective of reformers and was one of the more important provisions in the BRCA. Another way the post-Watergate election reforms were undermined was with the upsurge of interest groups running election ads These ads typically attack a candidate, but the sponsor can avoid disclosure and contribution limitations because the ads do not use electioneering language, such as “vote for” or “vote against” a specific candidate. Under BCRA, an electioneering communication is “any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication which refers to a clearly identified candidate for Federal office [and in the case of House and Senate candidates is targeted to their state or district], is made within 60 days before a general, special, or runoff election for the office sought by the candidate; or 30 days before a primary or preference election.” In 2007, the Supreme Court in a 5–4 decision declared the BCRA “electioneering communication” definition too broad and substituted a new definition that an ad is considered “express advocacy” only if there is no reasonable way to interpret it except “as an appeal to vote for or against a certain candidate.” One predictable consequence of BCRA’s ban on soft money, while leaving open the possibility of some electioneering communications, was increased interest group electioneering through so-called 527 or 501(c) groups. These groups get their names from the section of the Internal Revenue Service code under which they are organized. Section 501(c) groups include nonprofits whose purpose is not political. Money given to Section 501(c)(3) groups is tax deductible, and the groups can engage in nonpartisan voter registration and turnout efforts but cannot endorse a candidate. BCRA restricted the way 527 groups communicate with voters. Any 527 organization wishing to broadcast an electioneering communication within one month of a primary or two months of a general election must not use corporate or union treasury funds; it must report the expenditures associated with the broadcast; and it must disclose the sources of all funds it has received since January 1 of the preceding calendar year. The 527 group that may have had the greatest impact on the 2004 campaign was Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, which attacked Senator Kerry’s war record. The Supreme Court made clear in its ruling on FECA in 1976 that individuals and groups have the right to spend as much money as they wish for or against candidates as long as they are truly independent of the candidate and as long as the money is not corporate or union treasury money. BCRA does not constrain independent expenditures by groups, political parties, or individuals, as long as the expenditures by those individuals, parties, or groups are independent of the candidate and fully disclosed to the FECA. LECTURE 3: Each year, the money raised and spent in national elections hits new highs and raises more controversy. Develop an interesting lecture by concentrating on the financial base of presidential campaigns. Explore the decline of political parties as a source of funds, Nixon’s creation of the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), which became the source of most of the Watergate scandal, and the 1974 FECA Amendments that led to a partial public funding of presidential campaigns. Additionally, the increase in “independent expenditures” by private groups suspiciously well-coordinated with the candidate’s campaign efforts, and the role soft money played before 2002 (money given free of FECA restrictions to state and local parties for “party building”), are major topics. The functioning of House and Senate campaigns is worthy of special emphasis, especially the rapid rise of PACs since 1974: 600 PACs in 1974, 2,200 by 1980, and over 4,000 in 1990. In the 1990 elections, for example, corporate PACs had $100 million available for contribution, trade association PACs had $88 million, labor PACs had $85 million, and ideological PACs had $72 million. In 1990, PACs gave close to $150 million to congressional candidates, with less than 10 percent of it to challengers. The amounts were higher in 1992 and 1994, but the proportions were the same. Congressional campaign costs have increased far more than presidential costs since the 1974 FECA. Several cynical journalists have commented that we have the best Congress money can buy. The costs of campaigning and the purported impact of PACs and other special interests, such prominent parts of the most recent campaigns, are often cited as major causes of voter discontent. Close the lecture with efforts to reform campaign finance and the decisions of the courts to limit those efforts. Perhaps the most notable effort was the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. That act, however, has been blunted by decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court in Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life (2007), Davis v. Federal Election Commission (2008), and perhaps most famously in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). Discuss whether real change or reform will came from this legislation. Did the bill “have teeth,” or was it simply an idea that is long from being realized in modern-day elections? A discussion on “which party is more likely to push for further legislation” or “closing the loopholes in the current legislation” is also appropriate. Does campaign finance reform favor one party over the other? LECTURE 4: Concern about campaign finance stems from the possibility that candidates or parties, in their pursuit of campaign funds, will decide it is more important to represent their contributors than their conscience or the voters. Scandals involving the influence of money on policy are not new. In 1925, responding to the Teapot Dome scandal—in which a cabinet member was convicted of accepting bribes in 1922 for arranging the lease of federal land in Wyoming and California for private oil developments—Congress passed the Corrupt Practices Act, which required disclosure of campaign funds but was effectively toothless. The 1972 Watergate scandal—in which persons associated with the Nixon campaign broke into the Democratic Party headquarters to steal campaign documents and plant listening devices—led to media scrutiny and congressional investigations that discovered that large amounts of money from corporations and individuals had been deposited in secret bank accounts outside the country for political and campaign purposes. The public outcry from these discoveries prompted Congress to enact the body of reforms that still largely regulate the financing of federal elections. 9.4 Determine why campaigns have an important yet limited impact on election outcomes. LECTURE 1: Politicians tend to overestimate the impact of campaigns. Political scientists have found that campaigns have three major effects on voters: reinforcement, activation, and conversion. Campaigns can reinforce voters’ preferences for candidates. They can activate voters, getting them to contribute money or become active in campaigns. Finally, campaigns can also convert voters by changing their minds. In practice, however, campaigns primarily reinforce and activate. Only rarely do campaigns convert because several factors tend to weaken campaigns’ impact on voters: People have a remarkable capacity for selective perception—paying most attention to positions they already agree with and interpreting events according to their own predispositions. Although party identification is not as important as it once was, such factors still influence voting behavior. Incumbents start with a substantial advantage in terms of name recognition and an established record. LECTURE 2: Popular participation in government is part of the very definition of democracy. The long history of struggle to secure the right to vote—suffrage—reflects the democratizing of the American political system. Examine this history with your students. The founders could not agree on the wording of property qualifications for insertion into the Constitution, so they left the issue to the states, feeling safe in the knowledge that at the time every state had property qualifications for voting. The states themselves eliminated most property qualifications by 1840. Ratified in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment established that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Despite passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, voting rights continued to be denied, particularly to African Americans, from 1870 until 1964. There were also many “legal” methods of disenfranchisement, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and the white primary. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it unlawful for registrars to apply unequal standards in registration procedures or to reject applications. The Twenty-fourth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1964, made poll taxes—taxes required of all voters—unconstitutional as a requirement for voting in national elections. Congress enacted the strong Voting Rights Act in 1965, granting the U.S. attorney general, upon evidence of voter discrimination, the power to replace local registrars with federal registrars, abolish the literacy test, and register voters under simplified federal procedures. LECTURE 3: Students usually conceptualize voting as a right and responsibility of democratic citizenship. A lecture on the paradox of voting from an economic perspective provides an engaging (and often surprisingly fresh) way to approach this topic. The rational vote. From a purely “rational” perspective, a person should vote only if the costs of voting are less than the expected value of having the preferred candidate win, multiplied by the probability that one’s own vote will be the deciding vote. From a purely economic perspective, then, it often makes little sense to vote. The burden of registration. Voter registration remains an obstacle to voting, despite the easing of requirements for registration by many states. Burdensome voting. The contested 2000 presidential election spotlighted many of the flaws of ballots and vote counting throughout the nation. Help America Vote Act. Congress passed the Help America Vote Act in 2002 in reaction to the controversy surrounding the 2000 presidential election. LECTURE 4: While our students often take for granted that the voting age is 18, it has not always been so. Indeed, efforts to extend the franchise to young Americans and to encourage them to vote are relatively recent. The Twenty-sixth Amendment, ratified in 1971, established the voting age in the United States at 18 years of age. The amendment was passed in response to criticism that, prior to the Twenty-sixth Amendment, many young Americans were being drafted to fight in Vietnam but could not vote in elections affecting that war. The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, popularly known as the “Motor Voter Act,” mandates that the states offer people the opportunity to register to vote when they apply for driver’s licenses or welfare services. The intent of the law is to encourage more Americans to register to vote. 9.5 Identify the factors that influence whether people vote. LECTURE 1: Compared to nonvoting Americans, voters tend to be whiter, older, wealthier, and better educated. Evaluate how levels of voter turnout by various demographics affect public policy in the United States. Different demographics often have vastly different perspectives and political ideologies. They also have different opinions on public policy issues and, indeed, what issues should be considered important. For example, younger Americans tend to be more liberal than older Americans. Additionally, the groups may have different issues of concern. Younger Americans, for example, are more likely to be concerned with funding for higher education, while older Americans may be more concerned about Social Security and Medicare. Elected officials are more likely to respond to the demands of groups important to their electoral chances. Thus, nonvoting has clear political and policy implications. LECTURE 2: Examine the costs of voting with your students in greater detail. First, people must register to vote. While the process of voter registration varies from state to state, in most jurisdictions, voters cannot register on the day of the election. Almost every state requires prospective voters to register about a month before the election in which they will vote. Relatedly, in many states, voter registration rolls are used to select prospective candidates for jury duty. This may be a disincentive for some people to register to vote. Even once registered, voting ideally requires citizens to become informed about the issues and candidates. In some jurisdictions, this means not just deciding which candidates to choose from but familiarizing oneself with a myriad of initiatives and referenda. LECTURE 3: Explain why, despite the relatively high costs of voting, people still choose to vote. The reasons usually center on three primary areas: First, people worry that others will not participate and that therefore democracy may collapse. Given that, people decide to vote. Second, people may think about other benefits, such as a collective benefit, which everyone gets to enjoy even if each person did not individually cause it to happen. Third, people may consider selective benefits, such as satisfaction of having fulfilled one’s civic duty. LECTURE 4: Americans do not vote the way citizens in other democracies do. We are at the bottom of a list of 20 nations; only the Swiss vote at lower levels. What is the issue with Americans? The answer lies mostly in the legal barriers to voting. First, and perhaps most importantly, is the registration requirements. Americans have a two-step process for voting. First, they must register. Depending on what state they are in, they might be required to do so up to 60 days before the election. Some states have reduced the requirements for registration and have seen turnout increase. Fully 30 percent of eligible voters have not registered. Among registered voters, the turnout is 85 percent, which is comparable to the turnout rates of other nations. Second, elections in America are held on a single day during which voters are expected to find the time to participate amid their other activities. Early and absentee balloting has become easier in recent years, but early voting tends to not change the turnout. In other democracies, election day is a holiday, or elections are held over the weekend so that people can vote. Third, elections in America are held more often than in any other nation, so citizens suffer from voter fatigue. If citizens are required to vote too often, they may feel less urgency about voting in any given election. Fourth, American elections are designed to be a winner-take-all system—the candidates who receive the most votes get the seats. Thus, you could vote every year and see your party’s candidate always lose, leaving you feeling perpetually unrepresented. You may eventually say to yourself, why bother? Finally, the United States has a two-party system, which means that only two major parties are ever likely to win an election. The more narrowly focused a party, the more people can get behind it; the more the party has to build a coalition, the harder it is to agree with every item on the party’s agenda. LECTURE 5: Compare and contrast first-past-the-post and proportional-representation electoral systems, focusing in particular on the effects the two systems have on voter turnout and political participation. In the United States, we have a first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system. The country is divided into many electoral districts, and the candidate receiving the most votes in any given district is elected. First-past-the-post electoral systems tend to be commonly used in countries with single-member legislative districts, like the United States and the United Kingdom. This combination of first-past-the-post and single-member district electoral systems tends to create two-party systems. These have the advantage of stability but have the disadvantage of narrowing ideological representation to the center of the political spectrum, a phenomenon referred to as Duverger’s law. It is often argued that FPTP systems encourage tactical voting. In this situation, a person chooses between one of two candidates he or she perceives as being most likely to win. This may happen for two reasons. First, if a person has a strong preference against a particular candidate, a vote for a candidate unlikely to defeat him or her could be perceived as a vote in favor of the candidate the voter opposes. You often hear this refrain in American presidential elections. A voter with very liberal views prefers the Green Party candidate for president but strongly opposes the Republican Party candidate. The voter may calculate that the Green Party has no chance of winning. But his or her vote in favor of the Green candidate may undermine the vote of the Democratic candidate and lead to victory for the Republican candidate. The voter thus votes in favor of the Democrat, not because he or she agrees with the Democrat’s policies but because the Democrat has the greatest chance of defeating the Republican. A version of this phenomenon played out in the 2000 presidential election in Florida. Second, there is a feeling that votes for anyone but one of the two largest parties are “wasted votes.” This is often expressed by the sentiment that while you could vote for a third party, why would you, as they have no chance of winning a general election. This can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Countries with parliamentary political systems often use proportional-representation (PR) electoral systems. Under a proportional-representation system, seats are distributed in the legislature based on the proportion of the popular vote received by the party. Thus, if a political party receives 25 percent of the popular vote, they would receive one-quarter of the seats in the legislature. Proportional representation is generally used in countries with parliamentary systems. Countries like Brazil, Germany, Israel, Russia, South Africa, and Spain use PR systems. PR systems are often critiqued for fragmenting the legislature. Because parties receive seats in the legislature based on the proportion of the vote they receive, legislatures can sometimes have dozens of small parties represented. This often leads to the formation of unstable coalitions necessary to establish a government and facilitate the business of the legislature. Such coalitions, however, can often give small parties with more radical views a disproportionate role in the legislative process. 9.6 Assess the impact of party identification, candidate evaluations, and policy opinions on voting behavior. LECTURE 1: Explain the mandate theory of elections. The mandate theory of elections asserts that elections boil down to a contest between political ideas. From this perspective, the candidate who wins the election expresses the ideas with which the American public most agrees. Perhaps not surprisingly, elected political leaders often subscribe to the mandate theory. You see this demonstrated in numerous speeches. For example, consider the following: While campaigning for office in 1992, President Clinton asserted, “That’s why I am trying to be so specific in this campaign—to have a mandate, if elected, so the Congress will know what the American people have voted for.” Even more directly, after winning reelection in 2004, President Bush claimed, “When you win there is a feeling that the people have spoken and embraced your point of view, and that’s what I intend to tell the Congress.” It makes sense that elected leaders would want to advance the mandate theory. Their victory, they would like to believe, provides evidence that the people support their positions. Political scientists, however, generally reject the mandate theory. Instead, political scientists generally hold that elections are determined primarily by three factors: Voter party identification Voter evaluation of the candidates The match between voter policy positions and those of the candidates, which is sometimes called “policy voting” LECTURE 2: Explain the importance of party identification for electoral choice. The average voter does not pay close attention to politics. Partisan identification thus becomes a straightforward way to assess political issues and evaluate political candidates. Perhaps not surprisingly, party identification tends to be the strongest predictor of political choice. In most presidential elections, for example, 90 percent or more of “strong Democrats” will vote for the Democratic candidate, while 90 percent or more of “strong Republicans” will vote for the Republican candidate. Elections thus become about courting independent voters in the middle. LECTURE 3: Discuss the phenomenon of issue voting. “Issue voting” refers to the idea that people are inclined to support candidates who share their view on a particular issue. For issue voting to hold true, a number of conditions must be met: The voter must be aware of the issue and have an opinion about it. That issue must be important to the voter. The voter must be able to identify the position of a particular candidate on that issue. The voter must believe one candidate’s position more closely aligns with his or her own on that issue. When those conditions are met, issue voting suggests that voters will support candidates whose position mirrors their own, especially when the voter feels strongly about a particular issue. LECTURE 4: Examine the demographic factors associated with higher propensity to vote in the United States. Income. Income is positively correlated with voting. People with higher-than-average income tend to vote more often than people with lower incomes. Education. Education is positively correlated with voting. People with more education tend to vote more often than people with less education. Indeed, level of education is the single-best predictor of voting of any demographic variable. Race and ethnicity. There are important distinctions in voter turnout by race and ethnicity. Black and white Americans vote in roughly equal proportions. However, turnout among Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans tends to be much lower. Age. Older Americans tend to vote in much greater numbers than younger Americans. College-aged Americans tend to have the lowest turnout of any demographic. Sex. While historically there was a difference in turnout by sex, this disparity has declined over time. Today, women and men vote in roughly equal proportions. Why does this matter? Politicians need to know who to target with their ads and campaigns. Also, polls show that those on the upper end of the socioeconomic spectrum have much different preferences than those on the lower end of the scale. However, if everyone on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum were to vote, the results of our current elections would be quite different. 9.7 Evaluate the fairness of the Electoral College system for choosing the president. LECTURE 1: Electoral College myths or half truths. The Electoral College is misunderstood by many people, including political scientists. Here are some myths concerning it: The Electoral College was designed late in the Constitutional Convention when the delegates could not agree on other methods for electing the president. Actually, within the first two weeks of the Convention, James Wilson of Pennsylvania proposed electing the president by special electors. The Electoral College system prohibits the election of a president and a vice president from the same state. This misconception comes from the language of the Constitution, which prohibits an elector from casting both of his votes for individuals from the same state. It does not, however, prevent the election of a president and a vice president from the same state. Four times the Electoral College has elected a president that got fewer popular votes than his rival. Not exactly. This has happened only once, in 1888, when Cleveland got more popular votes but lost to Benjamin Harrison due solely to the Electoral College. The other two times that are usually lumped in with the 1888 election are the 1824 and 1876 elections. In 1824 Andrew Jackson got more popular votes than John Q. Adams, but it was the House of Representatives that elected Adams, not the Electoral College outright. In 1876 the Democrat Samuel Tilden got more popular votes than Hayes, but it was a special commission that allocated disputed electoral votes to Hayes, giving him the victory; again, not the Electoral College outright. In 2000, Texas governor George W. Bush won the U.S. presidency without winning the popular vote, even though the state of Florida and its over 400 votes that gave Bush the state were contested for his entire term. The Supreme Court decided the outcome. The Electoral College system stipulates that the plurality winner of a state’s popular votes gets all of the state’s electoral votes. The Framers did not stipulate how electors would be chosen. The method of selection was left to states. All but two states use the general ticket system, where the plurality winner of a state’s popular votes gets all of the state’s electoral votes. This produces the risk that the person winning the national popular vote may lose the election. But such a winner-take-all system is not required by the Constitution. Two states (Maine and Nebraska), in fact, do not use it, relying on the District Plan instead. The framers designed the Electoral College because they didn’t think the public was intelligent enough to elect a good president. There was some sentiment similar to this expressed at the convention. But probably the primary concern with popular election of the president was the significant population differences among the states. In other words, it was a political decision. To rely solely on population would have guaranteed that the president (at least early on) would have been selected by three or four of the most populous states. Under this arrangement, it would have been difficult to get nine states to ratify the Constitution. Electors can vote any way they want. Technically, they generally can. But of the thousands of electors who have cast a vote for president and vice president, very few (about .04 percent) have “defected.” This is due to the fact that the parties usually select people to be electors due to their faithfulness to the party. Furthermore, the Supreme Court has ruled (Ray v. Blair, 1952) that states may restrict the discretion of electors. LECTURE 2: In Federalist No. 68, Alexander Hamilton, writing as Publius, provides the theoretical justification for the delegates’ design for electing the president and the vice president: the Electoral College. Below is a brief outline of the essay with crucial or provocative quotes that should spark class discussion. Also, the framers did not designate in the Constitution how electors would be selected, but at least five times in this essay Hamilton expresses the view that electors ought to be selected by the voters. The method of selecting the president has not been criticized much by the AntiFederalists. This is because it is such a well-crafted system. “I venture somewhat further; and hesitate not to affirm, that if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.” In designing the system, the delegates were guided by the desire that the people would have a say in deciding who would hold this important office. This was accomplished by giving the choice to some men chosen by the people for this special purpose, not to a preestablished body of men, like Congress. The framers also wanted to ensure that that those making the decision would be best capable of analyzing the qualities needed in a president. “A small number of persons, selected by their fellow citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to so complicated an investigation.” The system, as designed by the framers, also provides an efficient check on mob violence and disorders by requiring that the electors meet in their respective state capitals. It was highly desirable that every obstacle should guard against cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These problems were most likely to come from foreign nations seeking to influence the election outcome. To prevent this, the framers kept the decision from any preestablished body, which foreign agents could seek to influence, constitutionally excluding office holders from serving as electors and by having electors meet all in one place. “Thus, without corrupting the body of the people, the immediate agents in the election will at least enter upon the task, free from any sinister bias.” Another desire was that the president be independent of all but the people. Had the Congress elected the president, he would hardly have been independent of the legislative branch. Each state has a number of electors equal to its representation in Congress (House and Senate). To win the presidency, a person has to receive a simple majority of all the electors. If no person does receive a simple majority, the House of Representatives will select from the top five (changed to the top three with the Twelfth Amendment) electoral vote getters, with each state casting one vote. LECTURE 3: Students are often surprised to learn that when they cast a ballot in the presidential election, they are not actually voting for a candidate but are instead selecting a slate of electors who will vote for the president on their behalf. Explain the functioning of the Electoral College to your students. The Electoral College was put into place by the framers so that people wouldn’t directly choose the president—which would privilege the large states—and so that the House of Representatives would not choose—which would violate the principles of separation of powers. The Electoral College is comprised of 538 electors, allocated to the states on the basis of their representation in the U.S. Congress. The most populous state, California, has 55 delegates. The least populous states—those like Wyoming and the Dakotas—have 3. States (except for Maine and Nebraska) assign their electoral votes through a winnertake-all system; whoever wins a plurality in a state gets that state’s entire electoral vote. To be elected president, a candidate must have at least 270 electoral votes. In most years, this is not a problem. However, under some circumstances—such as when a third-party candidate captures some states—it is possible that no candidate receives a majority in the Electoral College. According to the Twelfth Amendment, if no candidate receives a majority in the Electoral College, the president shall be selected by the House of Representatives and the vice president by the Senate. This occurred in 1801 (before passage of the Twelfth Amendment) and in 1825. LECTURE 4: The Electoral College is often criticized as an archaic institution, out of touch with the realities of contemporary life in the United States. Particularly after the outcome of the 2000 presidential election, where Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College to George W. Bush, calls for reform have been growing. Examine possible reforms with your students. The Florida ballot counting and recounting after the 2000 election and the fact that the winner of the popular vote did not become president prompted a national debate on the Electoral College. The most frequently proposed reform is direct popular election of the president. Another alternative to the Electoral College is sometimes called the National Bonus Plan. This plan would add another 102 electoral members to the current 538. These 102 members would be awarded on a winner-take-all basis to the candidate with the most votes, so long as that candidate received more than 40 percent of the popular vote. Finally, two states, Maine and Nebraska, have already adopted a district system in which the candidate who carries each congressional district gets that electoral vote and the candidate who carries the state gets the state’s two additional electoral votes. 9.8 Assess the advantages and disadvantages of the U.S. system of campaigns and elections. LECTURE 1: Explain the primary functions elections serve in U.S. politics. Elections socialize and institutionalize political activity, providing an outlet for political engagement. This prevents frustration from being expressed through other forms of protest, including demonstrations and riots. Elections also provide regular access to the levers of political power. They permit leaders to be changed regularly, without recourse to coups or assassinations seen in some countries. Finally, elections serve to reinforce the legitimacy of the government in the eyes of the people. LECTURE 2: Nonvoting would generate less concern if voters were a representative cross-section of the U.S. population. But the perceived benefits and costs of voting apparently do not fall evenly across all social groups. Voters differ from nonvoters in politically important ways. Examine these differences with your students. Voters are better educated than nonvoters. Older Americans are politically influential in part because candidates know they turn out at the polls. High-income people are more likely to vote than are low-income people. Income and education differences between participants and nonparticipants are even greater when other forms of political participation are considered. The greatest disparity in voter turnout is between Hispanics and others. Ask students to consider the importance of voting versus nonvoting. Voting is an expression of good citizenship, and it reinforces attachment to the nation and to democratic government. Nonvoting suggests alienation from the political system. The right to vote is more important to democratic government than voter turnout. It is easier to question whether the government truly represents “the people” when only half of the people vote even in a presidential election. Democratic governments cannot really ignore the interests of anyone who can vote. Voluntary nonvoting is not the same as being denied the suffrage. LECTURE 3: The election process is supposed to be fair and unbiased, but disproportional wealth, media coverage, and lack of opposition to incumbents are all factors in an increasingly limited election process. Explain the importance of each of these variables for your students. LECTURE 4: Explain the influence of partisan gerrymandering on congressional election in the United States. “Partisan gerrymandering” refers to the drawing of electoral district lines to favor one party over another. In the United States, the vast majority of congressional districts strongly favor either Republicans or Democrats. In those districts, the favored party’s nominee usually wins reelection easily. Consequently, electoral competition tends to occur at the level of the party nomination rather than in the general election. Seats in these electoral district are generally termed “safe seats,” since the incumbent officeholder generally retains the seat in elections by wide margins.