An Introduction to Qualitative Research

advertisement

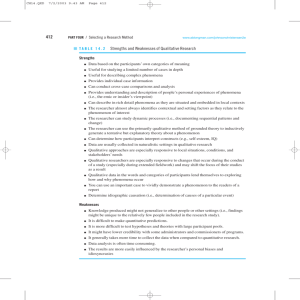

An Introduction to Qualitative Research Day 2 RADHIKA VIRURU, PH.D. DEPT. OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES QATAR UNIVERSITY Qualitative axioms (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) The nature of reality: multiple, constructed and holistic The relationship of knower to known: interactive, inseparable. Generalization: a “working hypothesis” that describes a single case Causal linkages: mutual simultaneous shaping. Inquiry is value bound. Characteristics of qualitative inquiry (ibid) Natural setting: phenomena take their meaning as much from their contexts as they do from themselves. Demands attention to multiplicities in situations. The human instrument: no other instrument can adjust to/appreciate multiple realities. Can cope with indeterminacy. Can respond immediately to data. Can be trained to be trustworthy Uses tacit knowledge. Qualitative methods (though not exclusively) : not anti quantitative but focuses more on the particular Characteristics of naturalistic inquiry Purposive sampling: try to choose a sample that gives you the widest range, to include as much information as possible (maximum variation sampling). Sampling is emergent; serial; continually focused and selected to the point of redundancy Inductive data analysis. Grounded theory: theory that emerges from the data and that “explains” the data. Negative case analysis Emergent design: “Tell me what questions I need to ask, and then answer them for me”. Emerges through continuous data analysis, interactions, peer debriefing, journals. Characteristics of naturalistic inquiry: Negotiated outcomes: obligation to consult participants. “Case study” reporting Idiographic (particular) rather than generalizable interpretations. Tentative application. Special criteria for trustworthiness. When to use qualitative research “Quality” versus “quantity”. For problems that need exploration For problems that need a complex detailed understanding. To empower individual and collective voices. To write in styles that push the limits of formal academic narratives To understand contexts The question of “fit” Five Approaches to Qualitative Research: Based on “Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Narrative Research Narrative research: begins with the experiences as expressed in lived and told stories of individuals Can take the form of biographical studies, life histories or oral histories. Collecting stories and “restorying them Example abstract In my research, which has involved collecting women’s accounts of becoming mothers, I am seeking to understand how women make sense of events throughout the process of child bearing, constructing these events into episodes, and thereby (apparently) maintaining unity within their lives Miller, T. (2000). Losing the plot: narrative construction and longitudinal childbirth research. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 309-323. Phenomonological research Describes the meaning for several individuals of their lived experience of a certain phenomena. Can center around basic broad questions: “what have you experienced in terms of the phenomena” and “what contexts have influenced your experience of the phenomena” Example abstract Given the intricacies of power and gender in the academy, what are doctoral advisement relationships between women advisors and women advisees really like? Heinrich, K. T. (1995). Doctoral advisement relationships between women. Journal of Higher Education. 66, pp. 447-469. Grounded theory research Employed in situations where it is perceived as necessary to go beyond description and generate theory. Use of the constant comparative method Can lead to follow up quantitative research Example abstract The primary purpose of this article is to present a grounded theory of academic change that is based on research based by two major research questions: What are the major sources of academic change? What are the major processes through which academic change occurs? Conrad, C.F. (1978). A grounded theory of academic change. Sociology of Education, 51, 101-112. Ethnographic research This kind of research focuses on an entire cultural group: describes their shared patterns of values, behavior, language and culture… Field work as method of data collection. Example abstract This article examines how the work and the talk of stadium employees reinforce certain meanings of baseball in society, and it reveals how this work and talk create and maintain ballpark culture Trujillo, N. (1992). Interpreting (the work and talk of) baseball. Western Journal of Communication, 56, 350-371. Case study research This kind of research involves the study of an issue explored through one or two cases within a setting or context. Example abstract The purpose of this study was to take a look into education through the eyes of three teachers who are facing their final year as professional educators. The overarching goal was to determine how they have seen children, teachers, administration, policy, and testing change across the thirty year span of their work as teachers in Texas’ public schools. Through their comments they give a considerable amount of insight into the transformation education has experienced in the last three decades. But unexpectedly, they reveal as much about our changing society than they do education itself. Project submitted in EDCI 690, Summer 2005, Texas A&M University. Designing and carrying out qualitative studies Designing naturalistic inquiries Naturalistic designs must emerge and unfold as the study progresses. Not all of the elements can be specified ahead of time, but some can. Determining where and from whom data will be collected. Identifying initial sample and making provisions for orderly evolution Phases of inquiry: (can overlap) Orientation and overview. Focused exploration Member checking Determining instrumentation: teams and training Designing naturalistic inquiries Planning data collection and recording: Interview/participant observation.. Recording: advantages of field notes over recording Planning data analysis procedures: must begin early and be ongoing. Planning logistics Planning for trustworthiness Participant observation (Spradley 1980) Dual purposes of participant observation: To engage in activities To observe activities Explicit awareness: becoming aware of things that you normally block out. Wide angle lens: wider circle of awareness Insider/outsider experiences. Introspection Record keeping Awareness of what is not there Kinds of participation Non participation (study of TV programs) Passive participation (courtroom spectator) Moderate participation (“watching” video games) Active participation (learning to do what others are doing) Complete participation Descriptive observations Based on descriptive questions that ethnographer has in mind Grand tour observations and mini tour observations Key things to observe: Space Actor Activities Objects Acts Events Time Goal Feelings Field notes Issues with taking notes openly: Assures that research is being carried out openly Cannot always take breaks (take time out) Do not always fit the situation Being careful about when to take them. Jottings: Include initial impressions Include descriptive and reflective notes. Small notepads Symbols Key events (both personal and collective) Increasing the value of jottings Include key components of scenes or interactions observed. Avoid making generalizations: don’t describe someone as inefficient, include details. Include sensory details: instead of describing someone as “angry”, describe them. Include speculation about motives as questions rather than facts. Experiment with what kinds of details jog the memory. Limit the time in the setting Form of field notes (Bogden and Biklen) Title and other identifying data. If taking notes on site, experiment with different ways of organizing notes. There is no one right way!! Use many paragraphs Leave large margins on the left side Language identification principle (Spradley) The verbatim principle Qualitative interviews Kinds of interviews: Informal. Not a major source of data but not without purpose. Can have some questions ready. Informants must know that these too are “data” Formal/semistructured: Planned ahead. Researcher in charge. Combination of structure and flexibility. Expect the unexpected. Standardized interviews: limited use in qualitative studies. Answers transcribed by researchers. Getting prepared: Thinking through what interviews can be done and with whom. Selecting participants Extreme or deviant case samples (Teacher of the Year) Maximum variation samples (different perspectives on same phenomena) Homogenous samples (individuals with similar characteristics) Typical samples (considered typical) Stratified purposeful samples (representing samples of interest) Snowball samples (one person identifies another) Criterion samples (individuals who fit certain criteria) Theory based samples Confirming and disconfirming samples Convenience samples In all cases, participants should know/negotiate the ground rules for the interviews. Developing questions Most qualitative interview questions are open ended. Hatch’s categorization Essential Extra or follow up questions Probing Throwaway/Background Spradley’s categorization: Descriptive Structural Contrast Writing effective questions: Language familiar to respondents Clear/neutral Respectful Qualities of good interviews Begin with small talk Listening: Follow up on of course statements Listen for key words Probing questions Use of why questions (Don’t ask for meaning, ask for use) Self disclosure Member checking (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) When to finish an interview: Information is redundant Fatigue on both sides Responses get guarded “play back” for the informant what has been said Invites respondent to validate the constructions made. Can induce respondent to add new materials that he or she is reminded of. Puts the respondent on record, so harder to deny it later. Taking notes (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Disadvantages: One cannot record everything. Rapid handwriting is sometimes undecipherable. Respondent may slow down to accommodate the interviewer and lose train of thought. Advantages: Forces careful attention Can interpolate questions or comments on to the notes without knowledge of interviewee. Notes can easily be flagged for follow ups Member checking is easier. Unobtrusive measures Gathered without direct involvement of the participants: does not interfere with ongoing activities. Artifacts. Traces: wear spots. Documents Personal communications Records Photographs Historical data Working with unobtrusive data Helpful in triangulation Explanations Must be careful about making interpretations Collections of data may not be organized. Specify ahead of time what kinds of unobtrusive data will be collected. Organize it carefully Building trustworthiness Journals Triangulation Debriefing Audit trail Validity and reliability in qualitative research or trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Common criticisms of qualitative research: Subjective; “loudest bangs or brightest lights”. Four common criteria: Internal validity (measuring what was intended): that changes in the dependent variable are caused by controlled variation of the independent variable. Common threats such as maturation, testing. External validity: relationship can be generalized across similar populations. Reliability: dependability, stability and consistency. Usually tested by replication. Objectivity: usual criteria is intersubjective agreement. Naturalistic trustworthiness criteria Credibility: activities that make it more likely that credible findings and interpretations will be produced. Prolonged engagement: the investment of sufficient time to where one can take account of distortions that might creep into data. Also a time to build trust. Persistent observation: identify salient characteristics of the situation. Triangulation: use of different sources, methods, investigators and theories (more problematic in naturalistic inquiry). Credibility Peer debriefing: talking to a disinterested peer about inquiry. Can test hypotheses Opportunity for catharsis. Referential adequacy: making data available for scrutiny. Member checks: not just at the end of an interview but at end of case study. May take an entire day with multiple stakeholders. Transferability and dependability Transferability is similar to external validity. Provision of thick description. Dependability and confirmability (similar to reliability): Overlap methods. Audit trails for both process (how study was conducted) and the product (if accurate or not). Reflexive journals Includes information both about self and method. Can include: Daily schedule and logistics of study. Personal diary Methodological log