Savannas and Dry Forests

advertisement

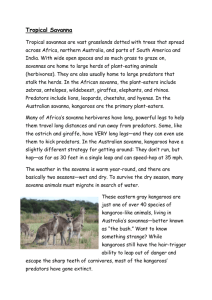

Savannas and Dry Forests Harvey E. Ballard, Jr. Department of Environmental and Plant Biology Ohio University Savannas and Dry Forests Questions Brief introduction Definitions and classifications Types of savanna and dry forest Determining factors Floristic composition--an example Savannas and Dry Forests Geologic History Ecological patterns Diversity and endemism Characteristic plants and animals Conservation Answers to initial questions Questions What type of savanna vegetation is the most widely distributed? What factors determine the development of savanna vegetation? What are some ecological patterns characteristic of savannas and dry forests? More Questions Are Neotropical savannas species-rich or species-poor communities? Which groups of organisms are well represented in savannas? Brief Introduction • “Rainforest” covers broad range of communities • Includes savannas and dry forests • These range from S Mexico to SE Brazil Brief Introduction • Vegetation intermingles with wet rainforest • Savanna may be uniformly wet, dry, or seasonal • “Savanna” and “dry forest” differ in tree cover (intergrade) Brief Introduction • Dominated by xeromorphic plants • “Treed grassland” or “treed desert” • Soils typically nutrient-poor • Fire important in some regions Brief Introduction • Negative human influences from cutting, agriculture • May be much more imperiled than previously thought--even worse off than wet rainforest! Definitions and Classifications Vegetation Formation Classes (Dansereau 1957) Class woodland savanna steppe Stratification woody pls>8 m woody pls=2-10 m herbs=0-2 m woody pls=0.1-2 m herbs=0-2 m Cover 25-60% 10-25% 25-100 0-25% 10-50% Definitions and Classifications Proposed Savanna Terminology (Cole 1963) Savanna woodland--deciduous/semi-deciduous woodland of tall trees>8 m high, and tall grasses>80 cm high; spacing of trees>canopy diameter Savanna parkland--tall grasses 40-80 cm high with scattered deciduous trees<8 m high Savanna grassland--tall tropical grassland, no woody plants Definitions and Classifications Proposed Savanna Terminology (cont.) Low tree and shrub savanna--widely spaced lowgrowing perennial grasses<80 cm high) with abundant annuals, widely spaced, low-growing trees and shrubs often<2 m high Thicket and scrub--trees and shrubs without stratification THOUGHT BY SOME TO BE MOST FLEXIBLE Types of Savanna and Dry Forest “Wet” communities • Llanos (Venezuela)—seasonally wet nearly treeless grassland of Orinoco floodplain • Pantanal (W Brazil, E Bolivia)—vast wet grassland in interior basin “Mesic” Communities • Chiquitanos (SE Bolivia)—dry to moist treed savanna/forest, newly discovered Types of Savanna and Dry Forest “Dry” Communities • Dry pine savanna (Belize)—Caribbean pinedominated savanna E of Maya Mountains • Dry forest (Costa Rica)—NW quarter of country, well studied by Dan Janzen et al. • Campos cerrados (central Brazil)—largest savanna area in Latin America, on deep sands; large pocket across central Guianas region • Caatinga (Brazil)—highly seasonal deciduous forest w/thorny woodies Determining Factors • • • • Climate Soil characteristics Fire Human influences Determining Factors Climate Determining Factors Soil characteristics Determining Factors Fire • Most types, including Campos Cerrados, show evidence of frequent fire • Morphological “adaptations” to withstand it • Extent of its role still debated— determines local savanna/forest borders? • [One source also suggested herbivory was important] Determining Factors No one natural factor explains distribution of the dry forest/ savanna biome Determining Factors Human influences • Conversion of savanna/forest to agriculture, grazing land; charcoal extraction • Higher ground-level temperatures (“albedo”) by loss of vegetation cover • Increased erosion, soil compaction • Reduced soil nutrients Floristic Composition-An Example Meta-analysis of floristic richness in Brazilian cerrados (Castro et al. 1999) • Compiled 145 lists for 78 repeatedly visited localities Floristic Composition-An Example • • • • 973 species 363 genera 88 families Many other unknown woody plants in all 3 categories • more research! Floristic Composition-An Example • 387 species (39%) grew at only one site • Over 50% of species grew in 1-2 sites! • Lower, upper limits inferred Floristic Composition-An Example • Lower limit--assumes all unknown already recorded in “known” species • Upper limit--takes data as is, all unknowns = new species • Other considerations, e. g., most sampling methods miss 5-20% of species present in sampled area Floristic Composition-An Example Trees/shrubs: Herbs/subshrubs: Total: 1000-2000 species 2000-5250 species 3000-7000+ species Cerrado vegetation much more species-rich than previously believed Floristic Composition-An Example How does this compare to other regions? Region Families Genera Spp. Cerrados: 88 363 30007000+ N. America 210 ?? 15000 Ecuador* 254 2110 15306 *includes angiosperms + gymnosperms Geologic History • No extensive macrofossil floras available, only microfossils (e.g., pollen, fibers) • Oldest savanna/dry forest fossils show up in Mid- to Late Eocene (12 mya) • Fossils only as isolated species or small populationsarid species in mesic matrix • Well developed and extensive dry system by Mid-Pliocene (4 mya) Geologic History Reciprocal invasions of genera between continents only since late Pliocene (2 mya) Geologic History • Repeated glacial periodsdrier climate, expansion of savanna • Increased speciation? Ecological Patterns Drought tolerance and responses--roots • root:shoot biomass ratio ca. 2 times higher (0.42-0.50) than that in wet forests (0.23) • root production higher • legume trees (Fabaceae) dominant, developing significant mycorrhizal assocations for N2 fixation Ecological Patterns Drought tolerance and responses--leaves • not well studied (e.g., desert plants) • trees and shrubs have sclerophyllous leaves, with thick cuticle and leathery texture • energy “cost” of producing these leaves much higher than in deciduous species • may also help against herbivory, etc. Ecological Patterns Drought tolerance and responses--stems • canopy trees ca. 1/2 as tall as those in wet forests • avg. canopy height in lowland tropical forest inverse to # months of <200 mm precipitation • root:shoot ratio differences of dry and wet forests may be partly due to stature Ecological Patterns Drought tolerance and responses--stems Diversity and Endemism Species diversity influenced by a variety of factors, including latitude Diversity and Endemism Life form diversity changes along aridity gradient Diversity and Endemism • Climatic regime “sifts out” non-drought resistant herbs and woodies • Many epiphytes, lianas and creepers resistant to environmental extremes become more dominant • CAM and C4 plants become important in hotter, drier sites • Succulents increase in dominance Diversity and Endemism • For conservation, areas of endemism are more important than areas of high diversity • Mexico’s dry forests have higher endemism than other communities; deserve attention • But endemism at generic level is lower over most savanna communities Diversity and Endemism • Endemism not previously evaluated at species level! • Each different dry forest/savanna type needs focus of conservation efforts Characteristic Plants • Legumes (Fabaceae) are commonest woody plants [and in Tropics generally!] Characteristic Plants • Many succulents (e.g., Agavaceae, Cactaceae) Characteristic Plants • Grasses (Poaceae) are dominant Characteristic Animals • Some birds “spill over” from nearby wet forests or wet grassland areas; some more restricted to dry forest/savanna • Reptiles and amphibians frequent • Substantial beetle and other insect populations, especially Carabids, Scarabs Conservation • Significant tracts in Mexico, southern Belize, NW Costa Rica, Bolivia, Venezuela, central Brazil • Some protection afforded to Guanacaste region of Costa Rica, little elsewhere • May be too late in some peripheral areas (Ecuador, Colombia, much of Central America) • Inaccessible tracts (Guianas)? Answers to Initial Questions What type of savanna vegetation is most widely distributed? The “campos cerrados”, a unique natural mosaic of grassland and open woodland on acidic, deep sandy soils, that dominates much of central Brazil but has many outliers The “caatinga”, highly seasonal dry forest/scrub, is also widely distributed Answers to Initial Questions What factors determine the development of savanna vegetation? • Climate--including seasonality (if exists) • Soils—nutrient-poor, but either well or poorly drained • Fire—natural or (more commonly) humaninduced • Human influences--cutting, agriculture Answers to Initial Questions What are some ecological patterns characteristic of savannas and dry forests? • High root:shoot biomass—partly due to short stature? • Substantial soil mycorrhizal relationships— principally in dominant Fabaceae • Xeromorphic leaf structure—thick cuticle, leathery leaves • Deciduous leaves—leaf fall during droughty periods Answers to Initial Questions Are Neotropical savannas species-rich or species-poor communities? Study of Brazilian cerrados suggests that this region is unexpectedly species-rich, (3,000-7,000 species) Answers to Initial Questions Which groups of organisms are especially well represented in savannas? • Angiosperms (Fabaceae, Agavaceae, Cactaceae, Poaceae) • Birds • Reptiles and amphibians • Beetles Bibliography Bullock, S. H., H. A. Mooney, and E. Medina (eds.). 1995. Seasonally dry tropical forests. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. Castro, A. A. J. F., F. R. Martins, J. Y. Tamashiro, and G. J. Shepherd. 1999. How rich is the flora of Brazilian cerrados? Ann. Mo. Bot. Garden 86:192-224. Cole, M. M. 1986. The savannas-Biogeography and geobotany. Academic Press, London, England. Goodland, R. J. A. 1966. On the savanna vegetation of Calabozo, Venezuela and Rupununi, British Guiana. Bol. Soc. Venezolana Cienc. Nat. 26:341-359. Bibliography Goodland, R. 1970. The savanna controversy: Background information on the Brasilian cerrado vegetation. McGill Univ. Savanna Res. Ser. 15., Montreal, Quebec. Hills, T. L. The savanna landscapes of the Amazon Basin. McGill Univ. Savanna Res. Ser. 14., Montreal, Quebec. Kricher, J. 1997. A Neotropical companion. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ. Proctor, J. (ed.). 1989. Mineral nutrients in tropical forest and savanna ecosystems. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, England. Bibliography Sarmiento, G. 1984. The ecology of Neotropical savannas. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA. Solbrig, O. T., E. Medina, and J. F. Silva (eds.). 1996. Biodiversity and savanna ecosystem processes-A global perspective. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.