Facial Trauma

Composed mainly of the frontal bone, temporal bones, nasal bone, zygomas, maxilla, and mandible.

Ethmoid, lacrimal, sphenoid bones contribute to inner portion of orbits

Upper third - above superior orbital rim

Middle third (midface)- superior orbital rim down through maxillary teeth

Lower third - mandible

Maxillofacial

Trauma

Patient evaluation

History

Physical exam

Other systems:

- Airway

- Circulation

- CNS (GCS)

Orbit

Nasal airway

Dental occlusion

Neurovascular

Contusion

Avulsion

Laceration

(loss of soft tissue – penetrating trauma)

First, inspect face for deformity and asymmetry

Enophthalmos, proptosis, ocular integrity, ocular movements

Nasal septum for position, integrity, and presence of septal hematoma

Epistaxis or CSF rhinorrhea

Complete neurological exam must be performed on any patient with suspected facial trauma

Sensation - test all 3 major branches of the trigeminal nerve

Motor function - assess facial nerve by having patient wrinkle forehead, smile, bare teeth, and close eyes tightly

Palpation of facial structures - the infraorbital and supraorbital ridges, zygoma, nasal bones, lower maxilla, and mandible

Assess for tenderness, bony deformities, crepitus, . . .

Malocclusion or step-off in dentition may be sign of mandibular fracture

Should focus on bony integrity, fluid-filled sinuses, herniation of orbital contents, and subcutaneous air

Overall status of the patient, physical exam findings, and the clinician’s initial impression determine timing and nature of imaging ordered

Traditionally the mainstay in the radiographic evaluation of facial trauma

Standard plain film facial series: Waters

(occipitomental), Caldwell

(occipitofrontal), and lateral views

Panoramic films are used to best evaluate mandibular fractures

Offers a viable, cost-effective alternative to plain films

Very helpful in the evaluation of facial trauma when facial edema, lacerations, other injuries, or altered level of consciousness limit usefulness of clinical exam

Limited role of MR in evaluation of facial trauma due to insensitivity of MR to fractures

Used to provide complimentary information to CT in the evaluation of the eye and its associated structures

Most common site of facial trauma due to location

May be displaced medialy, laterally or posteriorly

Requires control of epistaxis and drainage of septal hematoma, if present

Class 1 - frontal or frontolateral trauma

- vertical septal fracture

- depressed or displaced distal of nasal bones part

Class 2 - lateral trauma fracture

- horizontal or C-shaped septal fracture

- bony or cartilaginous septum

- frontal process of maxilla fracture

Class 3 - high velocity trauma

- fracture extends to ethmoid labyrinth

- bony septum rotates posteriorly

- bridge collapse up

- upturned tip, revealing nostrils

- depressed nasal bones pushed under frontal bones

- apparent inter-ocular space widening

Diagnosis:

- physical exam (asymmetry, deviation, epistaxis, swelling, . . .)

Radiography:

- do not have a role in management

Timing:

- before 10 days to 2 weeks

- within two hours after injury

Managements: (closed & open reduction)

Complications:

- septal hematoma

- CSF leakage

- ophthalmologic compl.

Tripod fracture: zygomaticofrontal suture, zygomaticotemporal suture, and infraorbital foramen

Present with flatness of the cheek, anesthesia in the distribution of the infraorbital nerve, diplopia, or palpable step defect

Le Fort I – maxilla

Le Fort II – maxilla, nasal bones, and medial aspects of orbits (pyramidal disjunction)

Le Fort III – maxilla, zygoma, nasal bones, ethmoids, vomer, and all lesser bones of the cranial base

(craniofacial disjunction)

Usually in combination

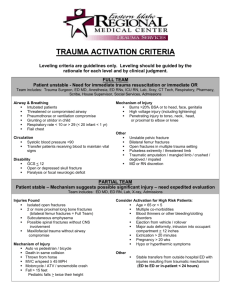

Fractures of the orbital floor may occur with orbital wall fractures or as an isolated injury.

When the orbital floor, being the weakest area, herniation of orbital contents down into the maxillary sinus may occur (hanging drop sign).

Patients may present with enophthalmos, impaired ocular motility, diplopia due to entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle within the fracture fragments, and infraorbital hypoesthesia.

Orbital Fractures

›

›

›

›

›

›

Usually through floor or medial wall

Enophthalmos

Anesthesia

Diplopia

Infraorbital stepoff deformity

Subcutaneous emphysema

This child presented with diplopia following blunt trauma to the right eye.

On exam, he was unable to move his right eyeball up on upward gaze.

A: Orbital blowout fracture with displacement of the floor

(arrow), distortion of the inferior rectus, and herniation of orbital fat through defect. Arrowhead indicates medial fracture.

B: Note opacified left anterior ethmoid air cells and displaced medial orbital fracture (arrowheads).

Frontal Sinus/Bone Fractures

›

›

Direct blow

Frequent intracranial injuries

›

›

›

›

Mucopyoceles

Consult with NS for treatment, disposition and antibiotics

Nasoethmoidal-Orbital Injuries

› Lacrimal apparatus disruption

Bimanual palpation if medial canthus pain

CT face

›

Orbital Fissure Syndrome

Fracture of the orbital canal

Extraocular motor palsies and blindness

If significant retrobulbar hemorrhage, may need cantholysis to save vision

›

Zygomatic Fractures

› Arch fracture

Tripod fracture

Most common

Most serious

Outpatient

Lateral subconjunctival hemorrhage

Need ORIF

Mandibular Fractures

›

›

›

›

›

›

Second most common facial fracture

› Plain films

Often multiple

› Panorex

Malocclusion

› CT

Intraoral lacerations

Sublingual ecchymosis

›

Nerve injury

Open Fractures

Prophylactic Ab.

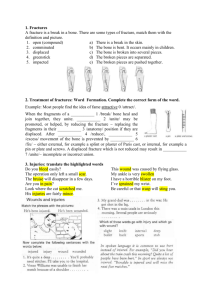

Simple

Greenstick fracture (rare, exclusively in children)

Fracture with no displacement (Linear)

Fracture with minimal displacement

Displaced fracture

Comminuted fracture

Extensive breakage with possible bone and soft tissue loss

Compound fracture

Severe and tooth bearing area fractures

Pathological fracture

(osteomyelities, neoplasm and generalized skeletal disease)

39

They can be vertically or horizontally in direction

They are influenced by the medial pterygoid-masseter “sling”

If the vertical direction of the fracture favours the unopposed action of medial pterygoid muscle, the posterior fragment will be pulled lingually

If the horizontal direction of the fracture favours the unopposed action of messeter and pterygoid muscles in upward direction, the posterior fragment will be pulled lingually

Favourable fracture line makes the reduced fragment easier to stabilize

41

Note fractures in left angle and right body of mandible

Multiple fractures are present more than 50% of the time and are usually on contralateral sides of the symphysis

Facial trauma is defined as injury to the soft tissues of the face (including the ears) and to the facial bony structures.

May result in hemorrhage and airway obstruction accompanied by multisystem involvement (as many as 60% of patients have associated injuries)

Evaluation includes history, physical exam, and diagnostic imaging

Reduction of fragments in good position

Immobilization until bony union occurs

These are achieved by:

Close reduction and immobilization

Open reduction and rigid fixation

Other objective of mandible fracture treatment:

Control of bleeding

Control of infection

45

No treatment

Soft diet

Maxillomandibular fixation

Open reduction - non-rigid fixation

Open reduction - rigid fixation

External pin fixation

Lag screw

Arch bars

▶ IMF prior to rigid fixation

▶ For the purpose of close reduction

48

TMJ ank.

Pediatric

Dental root

Inf. Alveolar N.

airway

Facial N.

Lacrimal ap.

Foreign body

Borders & margins injury

(Vermilion border- nasal ala- eyelidshelix)