roughdraft - UBC Blogs

advertisement

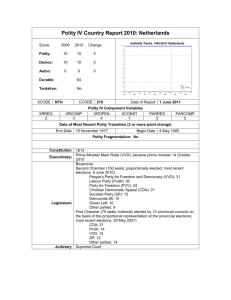

I have chosen three contrasting data sets to measure democracy in Turkey, Israel, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan: Polity IV, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Survey (FWS), and Political Regime Change (PRC). Each dataset has a unique conceptual foundation, thus each will provide different snapshots of the region. This contrast will serve to paint a comprehensive image of democracy in the Middle East. Both the PRC and Polity feature a gradated measure of democracy; the former presents Authoritarian, Semi-Democratic, and Democratic categories, whereas the latter rates a polity’s democracy/autocracy score on a -10+10 scale, with +10 representing the highest level of democracy. Alternately, Freedom House provides a representation of the lived experiences of people within a state, a valuable supplement to these governmentbased measures. It is important to note that all three datasets consider the protection of civil rights and liberties a necessary component of democracies and free states. Especially for the PRC and FWS, it is the combination of political and civil rights that allows a state to occupy the most favourable categories (Democratic and Free, respectively). Therefore, this paper defines democracy as a regime type that guarantees political competition, regulation, universal suffrage, and participation. Further, this regime must enshrine the political and civil rights necessary to ensure that the democratic functions of the regime are fulfilled in a systematic and legitimate fashion. This paper will provide a synopsis of each dataset, summarize the respective dataset’s applicability to the six countries in the region, and will integrate comparisons and critiques of the datasets throughout the analysis. Freedom in the World Survey Freedom House produces an annual Freedom in the World Survey, in which freedom is measured in 195 countries and 14 territories on the basis of two categories: political rights and civil liberties. There are 10 political rights questions and 15 civil liberties questions. Each question has a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 4, with 4 indicating the greatest degree of freedom. The “freedom rating” is the average of the political rights and civil liberties scores, and it determines a country’s overall status as Free, Partly Free, or Not Free. This rating is from 0-7, with 7 being the least free. Countries that meet certain standards are dubbed Electoral Democracies. Freedom House takes an individualistic human rights based approach, and operates on the premise that there are standards of freedom that should be universally upheld. Though Freedom House claims that the “survey does not maintain a culturebounded view of freedom,” this is a noticeably Western perspective. The most problematic aspect of the Freedom House measure is the broadness of the categories. A country with a score of 1-2.5 is Free, 3-5: Partly Free, and 5.5-7: Not Free. I question the notion that all the nations in the world can be adequately divided into three such categories. A state that scores a 3 could be vastly different than a state that scores a 5, yet their ranking on the data set would be the same. This calls the descriptive value of each category into question. The ambiguous explanations for these scores only exacerbate this problem. For example, a country that scores a 3-5 in the political rights category “moderately protects almost all political rights [or] more strongly protects some political rights while less strongly protecting others. The same factors that undermine freedom in countries with a rating of 2 may also weaken political rights in those with a rating of 3,4, or 5, but to an increasingly greater extent at each successive rating.” This is hardly enough information to develop an adequate grasp of the freedom that is enjoyed in a respective state. However, Freedom House is a consistent, annual database that provides easily interpreted data. Though not an adequate democracy measure in and of itself, the Freedom in the World dataset supplements Polity IV and PRC with a more individualistic measure. Fig.A: Freedom in the World Survey Scores Legend: (Political Rights score, Civil Liberties Score, Freedom House Score) PF = Partly Free, NF = Not Free, F = Free 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Turkey 2,4 PF 2,4 PF 2,4 PF 4,4 PF 5,5 PF 5,5 PF 4,5 PF 4,5 PF 4,5 PF 4,5 PF 4,5 PF 4,5 PF 3,4 PF 3,4 PF 3,4 PF 3,3 PF 3,3 PF 3,3 PF 3,3 PF 3,3 PF 3,3 PF Lebanon 6,5 NF 6,4 PF 5,4 PF 6,5 PF 6,5 PF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,3 PF 5,3 PF Syria 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,7 NF 7,6 NF 7,6 NF 7,6 NF 7,6 NF 7,6 NF Jordan 5,5 PF 4,4 PF 3,3 PF 4,4 PF 4,4 PF 4,4 PF 4,4 PF 4,4 PF 4,5 PF 4,4 PF 4,4 PF 5,5 PF 6,5 PF 5,5 PF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,4 PF 5,5 PF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF Israel 2,2 F 2,2 F 2,2 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,2 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,3 F 1,2 F 1,2 F 1,2 F 1,2 F 1,2 F 1,2 F Egypt 5,4 PF 5,5 PF 5,6 PF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,6 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF 6,5 NF Political Regime Change The PRC is designed for the specific purpose of classifying regime types and regime transitions. The PRC opts for a gradated definition of democracy, hence the inclusion of the “semi-democratic” category, and is opposed to dichotomous conceptions. The PRC seeks to remedy the heavy electoral bias seen in many measures of democracy, based on the argument that a regime is comprised of more than simply electoral processes. According to the PRC, a democratic regime is one in which meaningful competition and political participation exists, and the civil and political liberties necessary to ensure the integrity of the political system are respected. Conversely, an authoritarian regime is one in which “little or no meaningful political competition or freedom exists.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is the middle category that presents an issue. A semi-democracy is “a regime in which a substantial degree of political competition and freedom exist, but where the effective power of elected officials is limited, or political party competition is restricted, or the freedom and fairness of elections are compromised […]; and/or civil and political rights are so limited that some political orientations and interests are unable to organize and express themselves.” This category of “semidemocratic” can apply to so many different types of regimes that it is little more than a diminished subtype of democracy. Based on this definition, an essentially authoritarian state that affords some civil liberties and a democratic state that fails to protect civil liberties are classified as the same type of regime. Therefore, what value does “semidemocratic” have as a descriptive regime category? This is a similar issue to the one faced by Freedom House; a few broad categories are only so sufficient to describe the political freedom climate across the world. However, when combined with the individual-based Freedom in the World Survey and the more elaborate state-based Polity database, these broad regime categories provide a useful - if simplistic - accompaniment. Polity IV The Polity IV database focuses on the “polity,” or the organized state, as its unit of analysis. Therefore, Polity places emphasis on central authority, and aims to provide empirical descriptions of institutionalized authority patterns in a polity. The Polity database is more complex than either the Freedom in the World Survey or the PRC. Each state is described by a minimum of 16 variables, each of which has their own ranking system. Notably, Polity is not as successful at classifying regime types as the PRC; it has been shown that the variables for “autocracy” and “democracy” are essentially dummy variables (Reich). This means that an increase in autocratic value necessarily means a decrease in democratic value, and vice versa. Therefore, as explained by G. Reich, these variables are “collapsible.” The “polity score” is the sum of the democratic score minus that of the autocratic score, thus the supposedly gradated polity measure is somewhat compromised by the collapsible nature of these variables. That said, Polity is valuable in both detail and scope; the database involves many descriptive measures and various variables, and it covers a broad span of time. Whereas both PRC and the Freedom in the World Survey provide broad categorizations, Polity presents a more in depth analysis of political patterns. Turkey Turkey consistently scored moderately on the Freedom in the World Survey, and has been Partly Free from 1990-2010. Similarly, Turkey is considered by the PRC to be semi-democratic (1983-1998). It is worth noting that Turkey’s highest score in the FWS was a 2 in the Political Rights category from 1990-1992. This is consistent with Turkey’s Polity score of 9 between 1990-1992, the highest polity score the country has achieved in the past twenty years. Turkey has never been classified by the PRC or FWS as anything other than “partly free” or “semi-democratic,” suggesting that there has been no significant regime reform. However, the data from both FWS and from Polity IV shows a slight trend towards increased repression, most clearly indicated by the incrementally decreasing Polity Score. The consistency of the regime is further proven by Polity’s “Duration” variable, which indicates that as of 2010 the current Turkish regime had been in power for 27 years. Though there is a clear downward trend towards repression across the board, FWS classifies Turkey as an electoral democracy. Turkey must have achieved relatively high scores on various political rights questions in order to acquire this status, as civil liberties have not been well supported. Furthermore, the state receives moderate to high scores on many of Polity’s competition, participation, and executive constraint measurements. Based on these findings, it appears as though Turkey’s PRC ranking as a “semi-democratic” state is based predominantly on the state’s failure to enshrine various human and civil rights. Lebanon I would like to emphasize that from 1990 to 2004, Lebanon consistently scored -66 on various Polity measures. A -66 denotes either a “foreign interruption [or] system missing,” and there are virtually no values for Lebanon before 2004. This is moderately consistent with the findings of the PRC, which classifies Lebanon as “transitional” from 1989-1992 and “semi-democratic” from 1992-1999. In this case, the main shortcoming of PRC’s “semi-democratic” category is emphasized. Judging by the constant Polity -66s until 2004, presumably “semi-democratic” is a vague understatement. It certainly does not adequately describe a state that, according to Polity, did not have an established regime until 2005. Lebanon has shown some improvement in both the FWS and Polity databases; as of 2005, Polity classifies Lebanon as a democracy, and Lebanon’s FWS scores were at their highest from 2009-2010. According to FWS, Lebanon has emerged from a Not Free state in 1990 to a Partly Free state in 2010, and has noticeably improved in both the civil and political rights categories. Though Freedom House does not classify Lebanon as an electoral democracy, Polity shows high political freedoms scores as of 2005. According to Polity, Lebanon is now a state that boasts horizontal accountability in governance, regulated elections, and relatively high levels of competition. Presumably, similarly to Turkey, it is the lack of enshrined civil and human rights that prevent Lebanon from classifying as an electoral democracy in the FWS. Jordan Jordan has bounced between Freedom House scores 12 times in the past two decades (always between 3 and 5), yet, until 2009, had always classified as Partly Free. According to the PRC however, Jordan has been Authoritarian since 1946. It notable that Jordan, an almost consistently Partly Free state, and Syria, a consistently Not Free state, fall under the same category in the PRC. Jordan unfortunately elucidates the failures of broad FWS and PRC categories. Once again, I am left wondering what a one-point increase or decrease really means. Though the FWS Partly Free category fails to adequately describe the state, FWS’ findings are consistent with that of Polity; Jordan has been slowly declining into autocracy since 1990. The years 2007-2010 show Jordan’s highest Polity Autocracy scores to date. This is in contention with the FWS scores; 2009 and 2010 are the first years in the survey in which Jordan was constituted Not Free instead of Free. According to Polity (which still ranks Jordan as an autocracy) there is political competition in Jordan, but the competition is between warring factions or elites, and there are few executive restraints. Syria The Freedom in the World Survey has considered Syria to be a Not Free state since 1972. Similarly, according to PRC, Syria has been authoritarian since 1946. Though there was a one-point improvement in the FWS civil rights category between 2005 and 2006, Syria has remained a regime in which few or no political or civil liberties are protected or observed. This leads me to question what the value of this one point on the FWS scale is; neither the category nor the description of the regime changed between 2005 and 2006, yet a one-point improvement is shown. It seems almost arbitrary. Likewise, Syria’s polity score improved by 2 points between 1999 and 2000 (from -9 to 7), yet Syria remains staunchly autocratic. Chief executives are chosen by lineage or designation, competition is restricted and repressed, and there are very few executive restraints in place. Presumably, this two-point improvement in the Polity score in 2000 is connected to the 2-point improvement in executive restraints (as shown by variables Xconst and Exconst). I question if this improvement should be enough to significantly alter the polity score. In this case, FWS’ strict and consistent categorization of Syria as Not Free presents a usefully cohesive picture of the regime over the past two decades. Israel Israel is classified as an electoral democracy and Free state by Freedom House. The PRC confirms that Israel has been a democracy since 1949. All measures show that Israel has been a relatively political stable democracy since it’s modern inception; the biggest discrepancies are shown in the Polity dataset and occur between 1998 and 1999. Between these two years, the trends in Polity show that Israeli government became increasingly competitive and regulated. Egypt It is interesting to note that according to polity, the Egyptian regime technically reset in 2004. Presumably, this is in reference to the first elections that President Hosni Mubarak hosted in his 52-year reign. These elections are widely considered to have been fraudulent, and Mubarak was re-elected. Hence, I question the accuracy of the “Duration” Polity variable. Does this measure the duration of a given regime in theory or in practice? Since 2005, the Polity dataset cites notable increases in political competition, though I wonder to what extent this too, is based in theory. Neither the Freedom in the World Survey nor the PRC reflect the government reform that Polity suggests. According to FWS, Egypt has been Not Free since 1993, and the PRC classifies it as Authoritarian since 1922. Thus, it appears as though Polity places too much emphasis on official policy and not enough emphasis on policy in practice. I believe the PRC and FWS more accurately portray this regime. Conclusion These three datasets work best in combination with one another. Polity is in some ways the most informative dataset; it provides a clear breakdown of specific parts of the political system, which the other two datasets neglect to do. In this way, Polity often provides explanations for score increases or decreases in the PRC and FWS. Polity is thus most useful for explaining certain components of a polity, but is often less useful for painting an accurate picture of the regime as a whole. The interaction between the three datasets is perhaps best shown in the case of Egypt, where Polity recorded legitimate reform as of 2005. Freedom House, which accounts for the lived experiences of the population, and the PRC, which measures substantial regime change, reflected no such reform. Therefore the combination of the three datasets shows that while there was a perceptible shift in governance tactic, reform did not occur to such an extent as to positively impact the citizens of Egypt or constitute a regime re-classification. As of 2010, Turkey and Israel are the only two Electoral Democracies in this region, and Syria and Lebanon appear to house the most repressive regimes. Limited moves towards increased democracy are reflected in the Polity scores of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon, with Lebanon showing the most significant reforms in the past two decades. However, all three datasets clearly show that this is not a region in which democracy is currently flourishing.