Week 9: Knowledge Representation and Controlled

advertisement

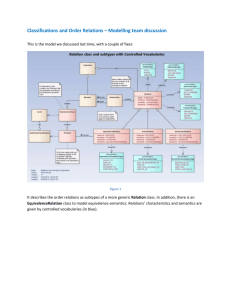

IUPUI School of Computing and Informatics S644 / I635 Consumer Health Informatics Week 9: Knowledge Representation and Controlled Vocabularies Contents Week 9 Learning Goals and Objectives......................................................................................................... 1 Week 9 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Week 9 Readings ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Week 9 Independent Learning Activities ...................................................................................................... 8 Week 9 Forum Discussion ............................................................................................................................. 9 Week 9 Learning Goals and Objectives Define and describe relevant terminology and concepts including ‘controlled vocabulary,’ ‘natural language,’ ‘keyword or text word,’ ‘metadata,’ ‘bibliographic database,’ and others. Explore a variety of consumer vocabulary initiatives including the UMLS and others. Consider and discuss the ways in which consumer vocabulary initiatives impact on the delivery of health information on the web. Explore and describe the difficulties and challenges faced by patients, families, or health consumers in using controlled vocabularies. Describe the issues and challenges, and potential benefits and drawbacks in adopting and using controlled vocabularies for CHI applications. 1 Week 9 Introduction Week 9 ends Module C: Telemedicine Tools. During Module C (Weeks 6 - 9), our class has explored a variety of consumer health websites, applied quality criterion to the evaluation of consumer health resources. We have discussed the importance of quality health information on the Internet or via mobile app, and recommended strategies for ensuring quality of consumer health information. You’ve learned a lot about quality assurance of consumer health resources! This week, we conclude Module C with a discussion about knowledge representation and consumer vocabularies. Framing questions are in italics throughout the mini-lecture: What is a consumer vocabulary? What is knowledge representation? How are these issues relevant in CHI? Standardized Medical Language Systems Using a vocabulary imposes a formal language-based structure on the materials that are included in the database of resources, and standardizes the ways in which information is organized and searched, mined, and used. In bibliographic databases (such as MEDLINE via OVID or PubMed), information retrieval is additionally assisted by keyword matches on well-constructed resource descriptions, or controlled vocabularies. In the information sciences, the concept of ‘controlled vocabulary’ brings to mind standardized ‘thesauri’ or ‘controlled vocabularies’ or ‘subject headings’ which are most often used for subject indexing in bibliographic databases like MEDLINE (OVID or PubMed), CINAHL, Psychological Abstracts, ERIC, and bibliographic databases of publications in various fields. Through the indexing process, specific controlled vocabulary terms are assigned to each journal article to represent its content. For example, MEDLINE (OVID or PubMed) searchers perform subject searches, using the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) controlled vocabulary to retrieve relevant articles. A sample MEDLINE citation, with MeSH highlighted appears below: 2 MeSH – Medical Subject Headings -- and other controlled vocabularies make it possible to find relevant information by identifying subject headings (MeSH terms). Instead of searching for keywords or text words or natural language words in the title, abstract, or text of an article, searchers select the MeSH controlled vocabulary term that best matches the concept for which they are searching. This dramatically improves retrieval. Other ontologies or controlled vocabularies are CLINICAL in nature – used in clinical care to organize concepts for diagnosis, treatment, billing, electronic medical records, and data mining. Clinical ontologies include ICD 9/10, DSM, and many others that are field-specific. A variety of controlled vocabularies or classification systems or ontologies or thesauri with which you may be familiar include: MeSH -- MEDLINE’s Medical Subject Headings CINAHL Descriptors – CINAHL nursing and allied health database subject headings ICD 9/10 -- International Statistical Classification of Diseases descriptors DSM IV/V -- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders classifications UMLS -- Unified Medical Language System SNOMED -- Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine As I said above, some of these ontologies are CLINICAL – used for coding treatment, diagnoses, and for billing (DSM, ICD). 3 Others are used more strictly for information retrieval from bibliographic databases (MeSH). What other nomenclatures or controlled vocabularies are used in your fields? What are the challenges and issues in using controlled vocabularies? The UMLS – Unified Medical Language System – is an effort of the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health to bring together a variety of ontologies into one large resource. It is a meta-thesaurus. A meta-thesaurus includes terms from many different thesauri. This is illustrated in the graphic below: In nursing, as an example, significant efforts have been to create nursing language systems such as thesauri and standardized classifications, to name and communicate what nurses do, for what patient problems arise, and with what results. Coding and specification of nursing language systems have been carried within the framework of the Nursing Minimum Data Set (NMDS). Nursing diagnosis, nursing interventions, and patient outcomes are among the nursing-specific elements of the NMDS. The American Nurses Association (ANA) has formally recognized 13 nursing language systems and is considering others. The Nursing Information and Data Set Evaluation Center (NIDSEC) qualifies languages in relation to ANA criteria of usefulness in supporting clinical practice. The language system must provide clinical useful terms and a rational for development, consist of clear and unambiguous terms, and provide evidence of reliability and validity. 4 Next, the way data are stored and made accessible for retrieval, and general system performance characteristics such as performance and attention to security and confidentiality are evaluated: North American Nursing Diagnosis Association, Inc. (NANDA) Nursing Interventions Classification System (NIC) Nursing Outcomes Classification System (NOC) Nursing Management Minimum Data Set (NMMDS) Home Health Care Classifications (HHCC) Omaha System Patient Care Data Set (PCDS) PeriOperative Nursing Dataset (PNDS) SNOMED CT Nursing Minimum Data Set (NMDS) International Classification for Nursing (ICNP®) ABCcodes Logical Observation Identifier Names & Codes (LOINC®) The above stands as an example of how specific fields have developed their own ontologies. The American Dental Association has its own ontologies as well! For the most part, these classification systems have been developed in parallel rather than in concert, with differing results. Language systems are either developed for a single purpose such as formalizing and expanding knowledge about professional practice, (e.g., the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association Taxonomy (NANDA)), or making explicit a profession’s role in health care, as with the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC), or the Nursing Outcome Classification (NOC). Some language systems combines nursing diagnosis with interventions and outcomes for particular settings such as Home Health Care Classification (HHCC) or are biased toward single disciplines such as the Perioperative Nursing data Set (PNDS). What impact do these initiatives and consumer vocabulary initiatives have on the delivery consumer health information and consumer health informatics? In contrast to MEDLINE and other highly-standardized bibliographic databases or classification systems, the web/Internet offers no controlled vocabulary or universally recognized search terminology. Instead, global search engines such as Yahoo, Google, and others provide loosely organized search directories within which content is organized according to broad categories. This process attempts to impose some simple 5 indexing structures. Unfortunately, and not unexpectedly, most search engines do not conduct formalized content indexing. In addition, the ‘rough’ indexes that do exist are not standardized across search engines. This makes looking for web-based information haphazard at best. Knowledge representation through the use of metadata is seen as a key to the development of machine understandable information that will enable computer software to perform intelligent searches, filter information automatically, or to tailor information to the individual. The goal is for the web to transform into a global medical knowledge base that is easily navigable and searchable across languages and continents. …This is the goal, at any rate! Clearly, we’re a long way off. How might this impact on CHI in practical application? Recent developments in metadata and meta-thesaurus standards, and the invention of eXtensible Markup Language (XML), Dublin Core metadata, MedPICS, and RDF (Resource Description Framework) are designed to present syntax and semantics that are compatible with HTML code, allowing web authors to tag their documents, ultimately leading to more effective retrieval. The Dublin Core Metadata initiative (DCMI), for example, spearheaded by OCLC (in Dublin, Ohio), is working to establish international consensus on the syntax and semantics of Internet-based content descriptions. DCMI promotes the widespread adoption of interoperable metadata standards and the development of specialized metadata vocabularies for describing resources that enable more intelligent information discovery systems. Other projects are creating ontologies based on natural language processing – taking the words and concepts that are used by average people doing routine tasks or searching on the web. Consumer Vocabularies Controlled vocabularies can also be discussed in the context of being within a website where consumers discuss their symptoms openly with others that have a disease or illness in common with them. Natural language processing, often called Folksonomies or folksomic tags are used to represent knowledge in sources and website such as PatientsLikeMe (www.patientslikeme.com). In one folksonomies project with PatientsLikeMe (Smith, 2008), each disease community member was asked to track ten “core symptoms” of their condition. The core list was first generated for the ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) community with input from healthcare practitioners and the indexed biomedical literature. Members could also report, in natural language, any additional symptoms they were experiencing. The result 6 was a semi-structured alphabetical list which patients can use as an assist for future symptom reporting. Parts of a Vocabulary Vocabularies typically consist of three high level components: (1) Surface forms or structure such as alphanumeric strings; (2) Underlying meanings representing distinct concepts; and (3) Relationships between concepts (forms-concepts). Yet, for a consumer health vocabulary to be useful it would, perhaps, have to be a more simplified collection of health expressions used by actual consumers and linked to professional concepts. This is the aim of consumer health vocabulary systems projects are to bridge the gap between everyday language and medical language. For example, there exists a consumer health vocabulary (CHV) initiative sponsored by the University of Utah, Department of Biomedical Informatics (http://consumerhealthvocab.chpc.utah.edu/CHVwiki/). This initiative is based on the understanding that lay people do not often use complex medical terminology, and certainly are not familiar with complex medical controlled vocabularies like MeSH or SNOMED. This project bring together technical terms and everyday terms so that lay people can use the terms with which they are familiar, but still find content that uses the official terminology. For example, technical terms such as "exanthema" can be translated into "rash," or “adaptation, psychological” can be translated into “coping.” The groundwork for the Utah consumer health vocabulary initiative began by mapping commonly used consumer health expressions to the UMLS thesaurus. Then reviewers (physicians, nurses, infomaticians, linguists, medical librarians, and patients) assessed the mappings to UMLS concepts and consumer friendly display (names) for the term. Entering the lay expression “ringing in the ear” as a search string returns the following, for example: CUI Term C0040264 tinnitus CHV Preferred Name UMLS Preferred Name ringing in the ear tinnitus Explanation of Consumer Term Disparaged no CUI: UMLS mapped concept ID Term: the term as known to be found in text string by professionals CHV Preferred Name: layman’s preferred name as defined in CHV, string 7 UMLS Preferred Name: preferred name for the CUI as defined by UMLS The CHV (consumer health vocabulary) initiative has the underpinnings of principles which were suggested by Zeng (2006): open access along with the three components which connect the relationship between form and concepts. To date, this is exactly the process through which consumer health vocabularies are creates; and the ULMS often stands as the meta-thesaurus upon which the vocabularies are built. So, the big question is: How does and will this impact on consumer health informatics? Zeng, Q., Tse, T., (2006) Exploring and developing consumer health vocabularies. JAMIA. 13:24–29. DOI 10.1197/jamia.M1761 Smith, C. A. and P. J. Wicks (2008). PatientsLikeMe: Consumer Health Vocabulary as a Folksonomy. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive T.A. Bakker, A. N. Ryce, et al. (2005). A Consumer Health Informatics (CHI) Toolbox: Challenges and Implications. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive. Week 9 Readings Lewis, Chapters 10 and 18 Computer-assisted update of a consumer health vocabulary through mining of social network data. Doing-Harris KM. Zeng-Treitler Q. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 13(2):e37, 2011. Exploring relations among semantic groups: a comparison of concept cooccurrence in biomedical sources. Kandula S. Zeng-Treitler Q. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics. 160(Pt 2):995-9, 2010. Week 9 Independent Learning Activities Read about the UMLS here: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/quickstart.html Explore one other ontology system, and share what you’ve learned with classmates! 8 Week 9 Forum Discussion This week’s framing questions are listed here. Also refer back to our mini-lecture. Why are controlled vocabularies important to information organization and searching? Explore and describe the difficulties and challenges faced by patients, families, or health consumers in using controlled vocabularies. What are the key features of the UMLS? How are the UMLS vocabularies used inpractice and useful in theory? How can our experiences with controlled vocabularies in bibliographic database searching using highly controlled thesauri be applied to highly uncontrolled consumer health tools? Explore the ways in which consumer vocabulary initiatives may impact on the delivery of health information on the web, via mobile apps, telehealth, and others. 9