Fate & Free Will - integrated life studies

advertisement

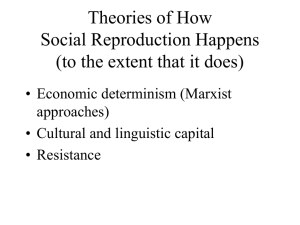

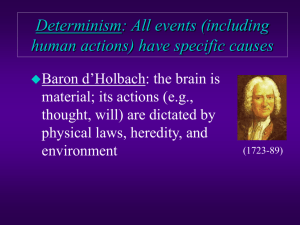

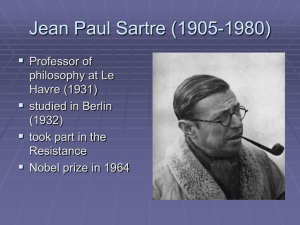

DETERMINISM v. FREE-WILL Am I the captain of my ship, or am I sailing on a ship controlled by some unknown auto-pilot? DEFINITIONS determinism - The view that every event has a cause and that everything in the universe is absolutely dependent on and governed by causal laws. Since determinists believe that all events, including human actions, are predetermined, determinism is typically thought to be incompatible with free will. For every event, there is a set of conditions such that if the conditions were repeated, the event would recur. The law of causality (or law of cause and effects) governs events. So even if we are not aware of those first events, determinism still assumes that an event is determined . (caused) by those first events. indeterminism - The view that there are events that do not have any cause; many proponents of free will believe that acts of choice are capable of not being determined by any physiological or psychological cause. A compatible view (but certainly not exactly the same as free will, which is discussed later) and yet still part of “indeterminism” is CHAOS THEORY, which says there are no causes, and yet given enough time, it will “appear” that there is enough regularity to suppose (erroneously) that there are causes for events. fatalism - The belief that "what will be will be," since all past, present, and future events . have already been predetermined by some impersonal cosmic force or power. In religion, this view may be called predestination; it holds that whether our souls go to Heaven or Hell (or Nirvana or no where) is determined by some personal power (i.e., God or the gods) before we are born and is independent of our good deeds. Both fatalism and predestination are “deterministic” in that (1) the assumption is that some thing or some one is controlling and determining our futures and that (2) there is little we can do to change our futures. Our futures are determined. . free will - The theory that human beings have freedom of choice or self-determination; that is, that given a situation, a person could have done other than what he did. Many philosophers have argued that free will is incompatible with determinism. See also indeterminism. If man has free will…. Determinism, Fatalism, and Predestination all clearly raise . questions about human freedom (although determinism only holds that if particular conditions occur as causes, then the effects will occur; if the causes of possible events do not occur, then that event will not occur either). If all events are caused (whether by fate, a god, or some other events), how can human actions (assuming that human actions are events), like your act of being in this class and reading these words, be free? The above question is one way of formulating what Philosophers call “the problem of free will.” THE PROBLEM OF FREE WILL The problem is important for a number of reasons, and one of the most important has to do with moral responsibility. If the choices we make and the actions we take are not free, then it makes no sense to praise or blame people for what they do. Whether it is fate, God, or other events that cause us to do certain things, then there is no reason for punishing us for doing “wrong” things, is there? The Dilemma: 1. Human choice is either free, or it is not free. 2. If it is free, then the law of causality is false. 3. If it is not free, then people are not responsible for their actions. 4. Therefore, either the law of causality is false, or people are not responsible for their actions. Neither of the choices in the conclusion (4) are very attractive. We want to believe the law of causality is true, and we want to make people responsible for their actions. If your future is determined by God, or the stars, or some . unknown first events that cause other events (which is the claim of determinism, fatalism, and predestination), then what sense does it make to say that you earned a good grade in philosophy, or that you merited a promotion at work, or that you ought to be punished for behaving badly? Hopefully, as we look at some things this evening, we’ll see some solutions to the “problem of free will” that had not occurred to us and our understanding of the problem itself will grow. “On Free Will” SIMPLE v. HARD DETERMINISM Simple Determinism refers to the idea that all events are caused. For every event, there is a set of conditions such that if the conditions were repeated, the event would recur. The law of causality (the law of cause and effects) governs events. So we can assume that any given event is caused by some previous event, even if we are not aware of what those previous events are. Simple determinism does not rule out the possibility that previous events (which are now the cause of current effects/events) were the result of choices we made in the past. Hard determinism holds that every event has a cause and that this fact is incompatible with free will. Nothing . happens for which there is not a sufficient reason; hence, free will is an illusion. Since any event or human action is unavoidable, we can’t blame a person for telling a lie any more than we can blame a leaf for falling off of a tree. Hard determinism holds that people are not in fact responsible for what they do in the sense that they could have made other choices than they did. Simple determinism, on the other hand, allows previous human choices to be the previous causes for given events, and thereby allows for the possibility of human free will as a causal factor. Supporters of hard determinism usually appeal to the . physical sciences and concepts like “natural law” to back up their views. Science seeks to give a description of objective facts. And if you recall, the difference between common-sense knowledge and science is that science is looking to find the uniform laws of nature which could explain the “facts.” These laws of nature (if discovered) are the networks of causes and effects according to which the events in the universe would be ordered. , BETTER ENVIRONMENTS, BETTER CHILDHOOS, ETC The debate over free will in not merely academic (or . limited to Philosophy discussions). It shows up, for example, when we discuss the roles that heredity and environment play on violent behavior, especially when we are talking about particularly perplexing and horrific crimes. Susan Smith shocked the whole nation when she killed her children. If you recall, she locked her two little boys in a car, rolled it into a lake, and drowned them. In order to prevent her from receiving the death penalty, her attorney, David Bruck, argued that she really had little control over her actions. Bruck argued that for all of her life, Susan Smith had been . a victim of destructive relationships (such as sexual abuse by her step-father). She also could not control the biological and mental fact that she suffered from depression and mental instability (which were the result of the destructive and abusive relationships). Her attorney did not argue that she was legally insane at the time of the drowning (because she did know the difference between right and wrong), but her defense was that outside factors were primarily the cause of the events that happened on the day her sons died. In other words, it was not her fault because she could not have acted differently. And a few years later, Andrea Yates deliberately and . systematically murdered her five children. When we hear these stories, we wonder if those people are truly in control of their own actions. What causes people to do such terrible things? Is it really “not their fault”? Two opposing tendencies drive our thoughts: 1. We want to believe that some inner agent called the “I” (me, my conscience) controls what we do no matter what our genetic inheritance or life experiences tend to be. 2. We want to know what makes us tick. We want science to be able to explain addictions (such as a genetic predisposition for alcoholism), sexual preference, crime, and a host of other behaviors. Can we have it both ways? Can we believe both that some free agent called the “self” is responsible for people’s actions AND that there are factors beyond people’s control that cause them to do what they do? The hard determinists say we cannot have it both ways. Free will and hard determinism . are incompatible. Hard determinism says that the idea of a free agent who is in control of what she does in such a way that she could have done otherwise at various points in our lives is just an illusion. Free will is a convenient fiction that we maintain out of our desire to punish and blame others for wrong doing and to congratulate ourselves for doing the right thing. It says “victim mentality” is true, because the victim could not have done otherwise than be a victim. We prefer the illusion of free will because it gives us the hope that we will not have to be a victim unless we make that choice to be a victim. LAURA WADDELL EKSTROM If hard determinism is true and what I do is always the only thing I could possible do, how could I have any free rein in conducting my life? Philosophers and Free Will Aristotle – “where it is on our power to act, it is also in our power to not act” Hume – liberty is “a power of acting or not acting according to the determinations of the will; that is, if we choose to remain at rest, we may; if we choose to move, we also may” (since there is no such thing as cause and effect) Kant – for an act to be truly free, “the act as well as its opposite must be within the power of the subject at the moment of its taking place” A.J.Ayer – “when I am said to have done something of my own free will, it is implied that I could have acted otherwise.” DEFINITION – The possession . of free will requires some times being able to do otherwise than what we actually do. Let’s say that an agent has free will only if some of the actions she performs during her lifetime are such that she can do (or could have done, but didn’t) otherwise. Ekstrom calls this “the minimal supposition of human free will” – the ability at some time to act other than acting precisely as he or she does act. THE COMPATABILITY QUESTION Does the truth of determinism imply the falsity of the minimal supposition of human free will? Hard causal determinism is the doctrine that there is at every instant exactly one physically possible future. The laws of nature are wholly deterministic, and every event is covered by or falls under a law. Incompatibilism says that determinism and free will are not compatible. Compatibilism says that even if determinism is true, it does not rule out person’s having free will. THE “SIMPLE” INCOMPATIBILIST ARGUMENT 1) The thought that all of my behavior is the causally necessary outcome of my genetic blueprint, environment, and social conditioning – in short, the thought that I am pushed into doing hat I do by what has come before me – undermines the idea that some of the acts I perform are genuinely “up to me. 2) Even if some things are “determined,” that does not rule out that I have choices at various times at a number of points with multiple options. (Recall the “minimal supposition of free will” says that at some time in my life, I will have the option and ability to act otherwise than how I do in fact act.) As depicted in figure 2.1, if one is a free agent, then as time proceeds from left to right, there are various juncture in one’s life and a number of alternate ways one might chose that, once chosen, alter the course of one’s life from that point on. Choose ME !!! Choosing a Spouse . There are a number of variables that range from when to whom. Which person you choose alters your life path considerably. If causal determinism is true, then at every instant of your life, there is exactly one physically possible future (and one person available to you for marriage, and so forth). Figure 2.2 illustrates that there . may be “apparent” forks in the road from the perspective of a person living in a deterministic universe, but exactly one of the “alternatives” is the one that the agent can actually take, since there is only one way, given the past and natural laws, that the course of events can proceed. . If causal determinism is true, then the agent cannot “get” to any of the alternative paths from the path he is on. Hence, it cannot be true that we have free will and that the doctrine of determinism is correct. One or the other of the suppositions is false. The Consequence Argument If determinism is true, then our acts are the consequences of the laws of nature and events in the remote past. But it is not up to us what went on before we were born, and neither is it up to us what the laws of nature are. Therefore, the consequences of these things (including our present acts) are not up to us. The Consequence Argument maintains every event is the causally necessary outcome of previous events, so that a chain of deterministically linked events stretches backwards into history. From a past event, given determinism, a person can trace a line forward through necessarily linked events up to each present events. There is a post hoc propter hoc fallacy, however, . See if you can figure it associated with this reasoning. out after you hear the argument again. Here it is: If determinism is true, since past events are now out of your control and what happens now because of previous events and laws of nature that are out of your control, then what happens now (as the outcome of those previous events and natural laws) is also out of your control. Modern day application (and this is TRUE!): I have a sister who lives in Atlanta, and every time I go to visit her when the Braves are playing a home game, the Braves lose. Did my going to Atlanta cause the Braves to lose? If I only visited my sister when the Braves were playing away-games, would the Braves have more winning seasons? But I cannot choose when I am going to visit my sister or when the Braves are going to win or lose, the determinist would say. LIBERTARIANISM First, do not confuse this kind of Libertarianism with the political movement of the same name. Libertarianism (to which Jean-Paul Sartre adheres) is the position that some human choices, in particular moral ones for which we can be held accountable, are NOT determined by previous events. The self (the part that makes choices) is not fixed by heredity, environment, or any other factor except our capacity for choice. We create who we are by the choices we make. We are RADICALLY FREE, the existentialists would say. EXISTENTIALISM Soren Kierkegaard, a Dane, is considered the founder of existentialism and turned 19th century Romantic optimism upside down by finding meaningful existence only in the possible, to which dread, rather than hope, is the key, and despair the path to minimal possibilities among the specters of frustration, sickness, pain, and death in God's inscrutable world. Jean-Paul Sartre, who was French like Descartes, argues that because he could not doubt that he was doubting with his back against a wall of nothing, he existed: Cogito, ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am"). The philosophy rose to prominence in the 1930s and '40s. Whether in the theological branch of Kierkegaard or the …atheistic branch of Sartre, existentialism shares six …essential aspects: 1. Existence before essence. All individuals are unique in ever new circumstances, in which they must act on their desperate choices. Through their choices and acts, they create their unique existence, their individual essence. 2. Impotence of reason. Humankind's presumed rationality cannot deal with the subterranean reaches of existence. But the existentialist sees reason powerless until merged with the irrational to make humans whole. . Scientific rationalism and a collective 3. Alienation. industrial materialism have alienated humans (a) from God, (b) from nature, (c) from society, and (d) from self. God is dead (Wilhelm Nietzsche, 1844-1900). We encase ourselves in shoes and walls, out of touch with nature. Each person is alone and unknown to those with whom she rubs elbows in the elevator. The self is fragmented into superego, ego, and id. "We are Hollow Men," says T.S. Eliot's mournful chorus. 4. Anxiety. Lost in the crowd, alienated even from self, . yet faced with the desperate choices even to exist, we live in an Age of Anxiety. God orders Abraham to violate "Thou shalt not kill" and sacrifice his son to prove his love and serve a higher command; Kierkegaard's point is that we must choose one abstract imperative over another, not in arrogance but in fear and trembling, only hoping the choice is right where moral laws contradict each other or fade altogether. In fear and trembling, we must frequently choose the exception to the rule because existence is unique, each circumstance exceptional. 5. Awful freedom. Since .human beings are free to become anything, to make their existential being through the act they must choose, their freedom is awesome and awful. The Christian existentialists fill the void with faith. Sartre filled it with will. Humans must move forward from black nothing into the moral void by choosing for themselves as if they were choosing for all, creating for themselves the essence of their being, and rediscovering, oddly, the old verities like "Love they neighbor as thyself," which Sartre believed have vanished. 6. Nothingness. NIHILISM, "nothing-ism," no reason for living, it is the realization that there is nothing before a . person but suffering and actual death; to stop is impossible, to go back is impossible; what one lives for is "nothing." The ultimate Christian dilemma of doubt and dread is the wish for death but the inability to die (or have the strength to commit suicide, physically or spiritually). Rejecting the past for present existence and its unique dilemmas, existentialism pervades the works of Franz Kafka, Sartre, Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco, Stephen Crane, and Hemingway. The Greeks asked, "What is Man?"; the existentialist asks, "Who have I made myself to be?" Jean-Paul Sartre (1899-1976) In 1964 he was offered the Nobel Prize for Literature, but refused to take it. While his political and philosophical views eventually fell from favor, Sartre remained a much respected character and when he died in 1980 over fifty thousand people attended his funeral. SARTRE’S Thought Sartre said that "existentialism is humanism." By this he meant that the existentialists start from nothing but humanity itself. His philosophy can be seen as a merciless analysis of the human situation when "God is dead." The expression "God is dead" came from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). The key word in Sartre's philosophy, as in Kierkegaard's, is "existence." But existence did not mean the same as being alive. Plants and animals are alive, they exist, but they do not have to think about what living implies. Man is the only living creature that is conscious of its own existence. Sartre said that a material thing is simply "in itself" (en soi) . soi). The being of man is but mankind is "for itself" (pour therefore not the same as the being of things. Sartre said that man's existence takes priority over whatever he might otherwise be. The fact that “I exist” takes priority over “what I am.” "Existence takes priority over essence." By essence we mean that which something consists of the nature, or being, of something. But according to Sartre, man has no such innate "nature." Man must therefore create himself. He must create his own nature or "essence," because it is not fixed in advance. . Throughout the history of philosophy, philosophers have sought to discover what man is - or what human nature is. But Sartre believed that man has no such eternal "nature" to fall back on. It is therefore useless to search for the meaning of life in general. We are condemned to improvise. We are like actors dragged onto the stage without having learned our lines, with no script and no prompter to whisper stage directions to us. We must decide for ourselves how to live. Bad Faith When people realize they are alive and will one day die and there is no meaning in life to cling to - they experience angst, Sartre said. You may recall that angst, a sense of dread, was also characteristic of Kierkegaard's description of a person in an existential situation. Sartre says that man feels alien in a world without meaning. When he describes man's "alienation," he is echoing the central ideas of Hegel and Marx. Man's feeling of alienation in the world creates a sense of despair, boredom, nausea, absurdity, and fear. Alienated from himself, Michael Jackson tries to assume responsibility for his own looks. But although there is no meaning to life, Sartre believed . that there is still human freedom and people should face up to this. "Man is condemned to be free," he said. "Condemned because he has not created himself - and is nevertheless free. Because having once been hurled into the world, he is responsible for everything he does." As self-conscious beings we have to make choices about how we live our lives. The choices we make are not connected to rationality. Sartre emphasized that we cannot hope to rationalize all the choices we have to make. Life consists of making choices but we do not always have good reasons for the choices we make. Sartre regarded this freedom to make choices as a great . we must understand and burden to bear but something accept. Some people find this hard. People who are scared by the burden of freedom sometimes fall victim to a kind of intellectual deception that Sartre calls "bad faith." They allow themselves to be misled into thinking that they do not have the freedom of choice. When people say things like "I'm just doing my job" they . they are using their job are guilty of bad faith because as a reason to avoid making their own choices. When someone denies that they have choice in this way they are acting as though they only exist en-soi rather than pour-soi. Saying that you can’t do or be something because of your parents’ lifestyle and how you were raised [or because of where you grew up - like on the “wrong side of the tracks” - or you don’t yet have enough money or you attended a second-rate college rather than an Ivy League one] is an excuse for not taking control of your own life and making the hard choices (many of which including OVER-COMING the “excuses” in order to succeed!). In many ways, Sartre’s philosophy sounds like a Nike commercial: . No excuses. Just do it! Those who thus slip into the anonymous masses will never be other than members of the impersonal flock, having fled from themselves into self-deception. On the other hand our freedom obliges us to make something of ourselves, to live "authentically" or "truly.“ To live “authentically” means to make our own choices and accept responsibility. Accepting any kind of determinism is a cop out and “bad faith.” LIVING IN “BAD FAITH”