The Insanity Defense

advertisement

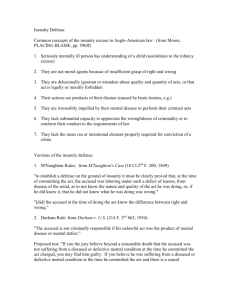

Running Head: THE INSANITY DEFENSE The Insanity Defense: Acquittal, Conviction, and their Intersection Angelica M. Ardines ENC 1102-Section 0014 Dr. Steffen Guenzel April 16, 2014 THE INSANITY DEFENSE 2 Abstract The insanity defense is the most controversial defense in the justice system. In this paper I will examine three different perspectives: those who completely oppose the insanity defense and call for convicting individuals who plea the insanity defense; those who support the insanity defense and call for acquitting individuals who plea the insanity defense; and the verdict of guilty but mentally ill, which serve as the intersection between the two perspective mentioned before. Many people have formed opinions on this defense based on misconceptions and thus they favor the abolishment of the insanity plea. Yet, despite its controversy and the misconceptions formed the insanity defense has been proven to be an important tool used in the justice system to uphold certain principles of criminal law. THE INSANITY DEFENSE 3 The Insanity Defense: Acquittal, Conviction, and their Intersection Introduction Andrea Yates, is a former nurse accused of drowning her five children in a bathtub. When asked why she did it Yates said that “she was being persecuted by Satan and needed to protect her children from eternal damnation by killing them” (Lilienfeld & Arkowitz, 2010). Her verdict was deemed as an outrageous decision: she was found not guilty by reasons of insanity. Andrea Yates had a history of severe postpartum depression, and this fact alone played a huge role in finding her legally insane. The insanity defense is one of the most controversial defenses in the criminal justice system of the United States. It is defined as, A defense asserted by an accused in a criminal prosecution to avoid liability for the commission of a crime because, at the time of the crime, the person did not appreciate the nature or quality or wrongfulness of the acts. (“Insanity Defense”, 2008) This ambiguous definition has led to complicated state statutes on how and under what circumstances to apply the insanity defense. In fact four states—Utah, Montana, Idaho, and Kansas—have banned it completely (Lilienfeld & Arkowitz, 2010). Due to the nature of its controversy the public has formed opinions based on myths that have worsen the understanding of the defense. Moreover, the insanity defense is not to be confused with incompetency to stand trial. A defendant is incompetent to stand trial if they cannot understand that he’s been tried and cannot tell the roles of the prosecutors, defense attorneys, and the judge. The insanity defense takes into account the mental health of the defendant at the time of the crime while competency takes into account mental health at the time of the trial. Furthermore, when the defendant pleas insanity they are either acquitted or convicted; but if the defendant is found to be incompetent to stand trial there is no trial proceeding, the defendant is then to receive THE INSANITY DEFENSE 4 proper treatment, and after being deemed competent they come back to court to receive a proper trial. (“Insanity Defense FAQs”, n.d.). Background: When and How Did the Insanity Defense Come to Be? Mentally ill individuals have been at the center of controversy and misunderstanding. During medieval times these individuals were thought to be possessed by demons and were left alone in dungeons. Often times they were burned at the stakes. This became even more apparent during the thirteenth century, the time of the Inquisition1 in Europe. Soon people began to question these measures and decided it was important to treat people who seem different from the rest and seem to have unexplainable behaviors. This led the ruling class of England to take measurements and soon they created England’s first mental hospital, Priory of St. Mary of Bethlehem Hospital, in London. However, at first the hospital admitted all kinds of patients; but around 1403 the hospital began to admit only mentally ill patients. This hospital was associated with “punishment and religious devotion” (“From Bethlehem to Bedlam”). Its terrible conditions became a source of entertainment for the upper class of England. During this century the English Lord Bracton established one of the first definitions of insanity. He explained that some people did not know what they were doing and this led them to act in a manner not too different from a brute. This then became the basic of what was known as the “wild beast standard.” Anybody who used this defense had to prove to the court that they had the minimum understanding of a wild animal or infant. This went on until 1843, when Daniel M'Naghten assassinated the prime minister’s secretary, Edward Drummond, an event that would change the insanity defense in the court systems of the world. Daniel M’Naghten shot and killed Edward Drummond, secretary to Prime Minister of England Sir Robert Peel. M’Naghten believed the prime minister was plotting against him, but 1 According to http://www.merriam-webster.com the Inquisition was “an organization in the Roman Catholic Church in the past that was responsible for finding and punishing people who did not accept its beliefs and practices.” THE INSANITY DEFENSE 5 instead of killing the prime minister he mistakenly killed his secretary. Once in trial M’Naghten’s attorneys plead acquaintance because the defendant was clearly insane and had no understanding of what he was doing. He was in fact acquitted of the crime2, a decision that stir the public. The House of Lords issued a ruling that read, To establish a defense on the ground of insanity it must clearly be proven that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing was wrong. (Gado, n.d.) This became known as the M’Naghten Rule, and for over a century it became the standard for the insanity defense (Gado, n.d.). According to pbs.org twenty-six states still use the M’Naghten Rule as a standard in their courts. However, these states have modified the rule to include irresistible impulses. In 1962, the American Law Institute (A.L.I.) created what is known as the Model Standard. It declares that a defendant can plea insanity, If at the time of his conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law. (Insanity defense FAQs, n.d.) Twenty-two states use the A.L.I. rule as their standard for the insanity defense. Conviction and how it is affected by Insanity Defense’s Misconceptions The ambiguity of the insanity defense has led many critics to refute it, and this has also affected the general public. However, many of their arguments are based on misconceptions rather than factual information. These misconceptions are going beyond shaping public opinion to actually shaping the verdict of the jurors in trials involving the insanity defense. 2 M’Naghten was sent to Bedlam and then to other mental institutions, where he didn’t receive proper treatment, due to the standards of the time, and died in 1863 (Gado, n.d.) THE INSANITY DEFENSE 6 According to Louden and Skeem (2007), jurors with negative attitudes towards the insanity defense are less likely to find a defendant insane. This creates a biased that could potentially hurt mentally ill defendants that do not receive the appropriate treatment. Daftary-Kapur, Groscup, O'Connor, Coffaro, and Galietta (2011) identified and studied eight different misconceptions about insanity: 1. The insanity defense is overused. It is not uncommon for the public to believe that the insanity defense is overused. However, research throughout the years have shown the opposite. In reality the insanity defense is used in less than 1% of all felony cases. For example, in a study conducted by Janofsky, Vandewalle, and Rappeport (1989), they recorded data during a twelve month period in Baltimore City Circuit Court and found that of the 11,497 defendants indicted, 143 plead insanity—only a 1.2% of the cases pleaded insanity. Daftary-Kapur et al (2011) reported that respondents believed that 37% in a sample of 1000 cases used the insanity defense. In fact, from the sample of 1000 cases only five pleaded insanity (as cited in Pasewark & Seidenzahl, 1979). 2. Defendants who plead insanity are usually faking. Another misconception held by the general public is that it is easy for defendants to trick the courts into believing they are insane. Janofsky et al. (1989) found that of the 143 cases who pled insanity only 38% were thought to be possibly insane. 28% of the defendants that were in fact referred for further evaluation were found not criminally responsible. It is hard to “trick” the justice system into believing that someone is insane. These individual usually have to go through several professionals before they can be found legally insane. THE INSANITY DEFENSE 7 3. Pleading NGRI (Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity) is a strategy used by defense attorneys to get their clients acquitted. Despite popular believe, attorneys have a hard task to successfully get their clients acquitted by reason of insanity. Janofsky et al. (1989) further their findings by identifying that defendants dropped the insanity plea in all but 16 cases; three of these cases failed to acquit; one of the thirteen remaining cases dropped the insanity defense because of “technical legal issues.” Only two of the twelve cases successfully held an insanity defense, and only one of them was found not criminally responsible. The NGRI verdict is very complicated; most defendants choose to drop the insanity defense. 4. The insanity defense is used almost exclusively in cases that involve violent crimes. Daftary-Kapur et al. (2011) observes that opponents of the insanity defense who believe that the insanity defense involves violent crimes for the most part hold this view due to the highly publicized trials involving the insanity defense (as cited in Steadman, Mulvey, & Monahan, 1998). The insanity defense can involve cases ranging from shoplifting to assault from the most part. It is a misconception to believe that it solely involve cases involving murders for the most part. 5. There is no risk to the defendant who pleads insanity. The no risk misconception is highly noted by supporters of the insanity defense. Unlike popular belief, people who plead insanity usually serve longer sentences than those who do not plea insanity. Daftary-Kapur et al. (2011) asserts that those defendants who unsuccessfully pled insanity serve a sentence 22% longer than those who did not use the insanity defense (as cited in Braff, Arvanites, & Steadman, 1983). Jurors see this as the defendant trying to escape punishment, therefore they should be sentenced with longer periods of time. THE INSANITY DEFENSE 8 6. NGRI acquittees spend much less time in custody than do defendants convicted of the same offense. Research conducted by Steadman et al. (1998) shows that defendants who have committed nonviolent crimes and successfully pled insanity spend nine times as long as defendants who did not plea the insanity defense and committed the same crime (Daftary-Kapur et al., 2011). Even those defendants that are successfully acquitted due to insanity, still have to be institutionalized in mental hospitals, and their stay is longer than expected. 7. NGRI acquittees are quickly released from custody. Continuing the view point above, critics believe that defendants that are hospitalized are there for a quick time and are then released. Daftary-Kapur et al. (2011) argues that only slightly above 1% of those hospitalized are released unconditionally (as cited in Silver, Cirincione, & Steadman, 1994). It takes more than just a couple of years to receive treatment for mental illness. In fact, these individuals are usually monitored and are not released until an expert and the court deems it appropriate. 8. Trials involving an NGRI defense almost always feature ‘‘battles of the expert.” The last misconception studied by Daftary-Kapur et al. (2011) is the fact that experts usually do not agree on the insanity plea. In reality 86% of 316 cases examined the prosecution did not contest the insanity defense; and in 81% of those 316 cases, health experts agree on the diagnosis made by the defense (as cited in Rogers, Bloom, & Manson, 1984). Acquittal: the Path to Righteousness For the most part people who favor the insanity defense and the acquittal of such individuals have built a strong case by rebutting the misconceptions of the opposing side. This has helped advocates of the insanity defense to strongly support their views throughout the THE INSANITY DEFENSE 9 years despite its controversy. From a very early period in time insane people have been treated harshly—many of them were left to die without receiving proper treatment. Even when hospitals were specially created for these individuals they were usually tortured. Unlike popular belief, individuals deemed as legally insane do not get a free pass to society; today they are sent to psychiatric hospitals and receive the proper treatment for their mental disorder. Andrea Yates was hospitalized in Texas, and was still there for more than four years after her acquittal (Lilienfeld and Arkowitz, 2010). Moreover, advocates of the insanity defense have noted how forty-eight out of the fifty states have some form of the insanity defense; if so many of the states support it, it means that the insanity defense is needed (Insanity Defense, n.d.). The insanity defense is not as easy to plea as the general public believe. This also leads to the fact that the insanity defense is not overused. Also, most people believe that the insanity defense usually involves murder trials. However, sixty to seventy percent of cases involving insanity defense come from crimes other than murder (they range from shoplifting to assault) (Insanity Defense, n.d.). Advocates’ argument appeals to the moral side of the issue—the insanity defense should be kept, because it is the right thing to do. Lilienfeld and Arkowitz (2010) note that it is not a matter of justice, but rather a matter of “bona fide mental disorder.” Why should a person be punished, when they had no control over their actions? In 1998 John P. Martin reported in the Washington Post [The insanity defense] allows judges and juries to decide some defendants aren't "criminally responsible" for their actions even though those acts might be a crime under different circumstances, just as a child who accidentally starts a fire shouldn't be treated as an arsonist. People who are truly insane lack the restrains that people generally have—they do what “normal” people know as immoral, because they either do not know that what they are doing is wrong, or they cannot control the impulse. The insanity defense is based on principle of THE INSANITY DEFENSE 10 criminal law—if someone committed a crime, they should be criminally responsible for this crime as a moral agent. Insane people do not have the capacity to morally assimilate their actions due to their mental illness or disorder, therefore, it would be unfair to punish them. “Guilty but Mentally Ill”: The Intersection between Conviction and Acquittal “Guilty but mentally ill” is the point of compromise between those who believe that people deemed insane should be punished for their crimes and those who believe that they should receive proper treatment. Someone who is found guilty but mentally ill is convicted and sent to jail, but while in jail they are supposed to receive treatment. However, to be found guilty but mentally ill is just as ambiguous as been found not guilty by reason of insanity; this verdict has not made the process of persecuting criminally insane people any easier. Those who oppose the GBMI verdict claim that those criminals sent to jail but are found mentally ill often times do not get the treatment needed for their mental illness. GundlachEvans (2006) claims that those individuals placed in prisons after being found guilty but mentally ill do not have to receive mandatory treatment. This takes us back to the times where insane people were sent to mental hospitals and were left there without treatment to die. As mention before people who decide to use the insanity defense often times commit crimes that range from shoplifting to assault. If these individuals are found guilty but mentally ill they are going to be sentenced for a certain period of time. They will eventually get out, but if they did not receive the treatment needed this creates a cycle, where the mentally ill individual keeps committing crimes and keeps getting sent to prison without receiving the proper treatment. Furthermore, because of the ambiguity of the guilty but mentally ill verdict, it is usually hard to choose between finding someone not guilty by reasons of insanity and finding someone guilty but mentally ill. In fact, both verdicts are very similar when it comes to their legal definition. To be found guilty but mentally ill the defendant has to have pleaded insanity. This clashes with the principle of criminal law mentioned above: to be found guilty of a crime as a moral agent—capacity that insane people lack. THE INSANITY DEFENSE 11 What is the Role of the Insanity Defense? After researching about the insanity defense it has become clear that it has an important role in the justice system. Individuals that do not have the capacity to understand the wrongfulness of their actions should not be held accountable for such acts—it is dehumanizing and immoral to do so. In fact principles of criminal law would be held inaccurate if one was to convict those individuals. Furthermore, I have also come to find out that the public holds many misconceptions about the insanity defense. It is important to understand that the insanity defense is not implemented as often as it is believed and that this defense is not taken lightly in the justice system. In summary, the insanity defense is not a free pass to freedom in society, but rather a defense based on a very important principle of criminal law—it is a very unusual exception, which proves that criminals should be held accountable for their actions. THE INSANITY DEFENSE 12 References Braff, J., Arvanites, T., & Steadman, H. J. (1983). Detention patterns of successful and unsuccessful insanity defendants. Criminology, 21, 439–448 Daftary-Kapur, T., Groscup, J. L., O'Connor, M., Coffaro, F., & Galietta, M. (2011). Measuring knowledge of the insanity defense: Scale construction and validation. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(1), 40-63. doi:10.1002/bsl.938 From Bethlehem to Bedlam - England’s first mental institution. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/people-and-places/disabilityhistory/1050- 1485/from-bethlehem-to-bedlam/ Gado, M. (n.d.). The insanity defense. Retrieved from http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/psychology/insanity/3.html Gundlach-Evans, A. D. (2006). State v. Calin: The Paradox of the Insanity Defense and Guilty but Mentally Ill Statute, Recognizing Impairment without Affording Treatment. South Dakota Law Review, 51(1), 122-151. Insanity defense FAQs. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/crime/trial/faqs.html Insanity Defense. (n.d.). West's Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. (2008). Retrieved from http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Insanity+Defense Janofsky, J. S., Vandewalle, M. B., & Rappeport, J. R. (1989). Defendants pleading insanity: An analysis of outcome. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry & the Law, 17(2), 203-211. Lilienfeld, S. O., & Arkowitz, H. (2010, December 23). The insanity verdict on trial. Retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-insanity-verdict-on-trial/ Louden, J., & Skeem, J. L. (2007). Constructing insanity: jurors' prototypes, attitudes, and legal decision-making. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 25(4), 449-470. doi:10.1002/bsl.760 THE INSANITY DEFENSE 13 Martin, J. P. (1998, February 27). The insanity defense: A closer look. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/local/longterm/aron/qa227.htm Pasewark, R. A., & Seidenzahl, D. (1979). Opinions concerning the insanity plea and criminality among mental patients. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 7, 199–202. Rogers, J. L., Bloom, J. D., & Manson, S. M. (1984). Insanity defenses: Contested or conceded? American Journal of Psychiatry, 141, 885–888 Silver, E., Cirincione, C., & Steadman, H. J. (1994). Demythologizing inaccurate perceptions of the insanity defense. Law and Human Behavior, 18, 63–70 Steadman, H. J., Mulvey, E. P., & Monahan, J. (1998). Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 393–401