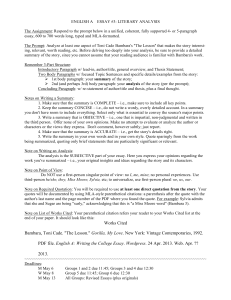

Sample Student Fiction Essay A

advertisement

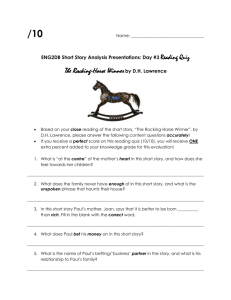

xxxx1 xxxx Instructor: Kristin Abraham ENGL 1020-60 21 June, 2011 A Yearning for Money: Fatal or Liberating? D.H. Lawrence’s “The Rocking-Horse Winner” and Toni Cade Bambara’s “The Lesson” outwardly relate the same tale – that of a young child’s first experiences with the concept of poverty versus wealth, and their subsequent reaction. Lawrence’s account focuses on a boy named Paul whose profound faith in luck prompts him to amass a small fortune through superstitious bets on horse races, but the wealth he possesses never seems to be enough; in the end, he works himself literally to death in his quest for riches. In “The Lesson,” by contrast, a teacher takes a group of impoverished African-American children to visit a store brimming with fabulous, expensive toys and guides them to a realization of the injustice of the massive class division, thereby planting a drive to fight for equality and social justice in the young generation. Therefore, both stories hinge on the complex theme of the children’s consuming desire to match others’ financial status, but a dissection of their subthemes and of the variation in their respective settings (1930s England versus 1970s America) reveals the authors’ slightly differing interpretations of the matter. Both Lawrence and Bambara weave tales in which the youthful characters witness a discrepancy between their families’ monetary status and what they view as a fair distribution of the wealth, which prompts them to action in an attempt to remedy the situation. In “The Rocking-Horse Winner,” two factors drive Paul to his inadvertent, self-destructive gambling addiction as a means of obtaining money: luck and “more.” Early in the story, he asks his xxxx2 mother to define luck, to which she simply responds, “It’s what causes you to have money” (Lawrence 223). This mindset implicates that the acquisition of wealth is beyond our control, determined by God, the stars, or fate; hard work, it follows, is pointless, and we are victims of chance rather than controllers of our own lots in life. Additionally, this concept of luck holds that wealth is the height of blessedness or good fortune, and those not in possession of riches are at a deficit. Those who are “unlucky” financially, then, are deprived of a randomly-bestowed award that they feel entitled to. This explains why Paul is drawn to gambling – since there is no tangible reason for his family’s seemingly cursed state, yet that state persists, no “real world” solution can remedy it. Instead, success is dependent upon using fate to his own advantage. Lawrence crafted Paul an appropriately superstitious means of harnessing his alleged luck – violently rocking on his wooden horse until he develops a hunch – strikingly similar to the practice in many Eastern religions of repeating mantas and entering trances in order to arrive at some sort of cosmic revelation (Hunt and Penwell 187, 219, 269, 606). The author further uses the concept of more, more, more to express people’s foolish sense of victimization and deprivation when they lack money. The more winnings Paul brings home to his family, the more they spend in a desperate, exponential effort to elevate their “social position,” to the extent that the very walls whisper with increasing intensity, “There must be more money! There must be more money!” (Lawrence 222). The family is so focused on how much more others have than they do, that they forgo contentment even with their steadilyincreasing wealth. When taken in the context of the entire universe, no level of wealth is impossible, so even the second richest person on Earth is to feel cheated, solely because he is not the first. xxxx3 Lawrence shows that because people with this mindset do not feel responsible for their own success, they feel entitled to the utmost degree of wealth simply because they are alive; since all but a few cannot possibly attain this level, particularly through luck, they condemn themselves to a lifetime of feeling cheated. The author, nearing the end of his life and suffering from chronic lung problems at the time of writing “The Rocking-Horse Winner,” undoubtedly experienced “a terrible state of urgency” (Murray 13) to impart this dire warning to humanity before he died; Lawrence himself was known for loving his life despite that much of it was spent in poverty (Murray 7), so the concept behind this story was clearly very close to his heart. His passionate tale forebodes that, like the infamous horror film dream sequence in which you run toward the end of an ever-lengthening hallway, the type of people who embrace his characters’ mindset entrap themselves in an endless cycle of acquisition followed by discontentment as they haphazardly pursue an impossible dream. Bambara’s story, in contrast, features not a grave warning, but a battle cry. Her tale features a teacher named Miss Moore who takes a group of poor children on a fieldtrip to a highend store with the objective that, by subjecting them to the presence of such unimaginable opulence, they will be forced out of their contentedly complacent spheres and realize how utterly unjust the vast separation between the classes is. When the children first arrive at the store, they are initially enraptured by such luxuries as a microscope and an intricately-designed model sailboat. They experience feelings of “shame” and inferiority, almost as if they do not belong in the store, and even anger that owning these treasures is far beyond their reach (Bambara 315). These emotions, however, are quickly replaced by a realization of how ludicrous these extravagances are. The rich are throwing away money on ridiculous items that will be break or be tossed away within days, all while so many others are living paycheck to paycheck. The xxxx4 cheapest item mentioned in the store – a $35 toy clown – could fund an entire family’s vacation to the country, and the $1,195 sailboat is equivalent to an annual salary for poorer families in that day (Korb 1-2). The narrator, Sylvia, asks incredulously, “Who are these people that spend that much for performing clowns and $1,000 for toy sailboats?” (Bambara 316). How is it a just world where some flippantly waste an amount that is merely a fraction of their fortune, yet is an incomprehensible amount to another family and could change their lives? Are they truly human? To the children in the story, and by extension to the readers, the focus is not on the victimization of some, but on the villainy of others. “The Lesson” teaches us not to be outraged by an injustice committed against us, but by any injustice committed, period. The villains in this story are not men who have more – Bambara certainly doesn’t present possession in itself as a crime – but the men who have the means to help others, yet choose to ignore that need and frivolously waste those resources. In this, Bambara’s story condemns selfish focus on our own lack just as much as Lawrence’s. “The Lesson” is intended to teach not the young characters, but the readers. Critic Toni Morrison said of Bambara, “There [is] no doubt that the work she did had work to do [in the readers’ hearts]” (qtd. in Korb 1). Similarly, Bambara guides her readers right alongside the children, revealing to them that poverty is not a curse upon a few families, but a plague that affects our entire society, and as such, we need to collectively fight to demolish the scourge and bring justice to all Americans, and ultimately, to humanity as a whole. Further emphasizing the importance of viewing the story as a lesson meant for ourselves is Bambara’s real-life similarity to Miss Moore. The character is based on Bambara’s childhood heroes Miss Gladys and Miss Naomi, women in her neighborhood who mentored children and taught them important life lessons (Deck 3). Miss Moore is also based on Bambara herself – notice that both are college xxxx5 educated women who choose to remain in the slums and educate the poor on social issues simply out of their love for other human beings and a passion to see social justice realized (“Toni Cade Bambara” 3-5). Clearly, all these similarities are intended to drive home the message that readers are expected to act as attentive pupils rather than merely seeking to be entertained by her story. Bambara’s tale, though openly reproving only those who hoard their fortunes, carries a message to prompt every reader to action. Indeed, “The Lesson” is that, though we may fight in different ways, we all – whether rich, poor, or somewhere in-between – need to engage in a personal battle to promote a fair chance for the impoverished. It is our duty to justice itself, and it is what allows us to retain our humanity These two stories have starkly different endings. Whereas, in “The Rocking-Horse Winner,” Paul becomes so obsessed with winning more and more from the races that loses his mind and dies of fever, the children in “The Lesson” conclude their fieldtrip by contemplating social justice, and as the narrator phrases it, “somethin weird is goin on, I can feel it in my chest” ( Bambara 316) as they are motivated to “race” on (Bambara 316) toward a victory for justice. On one hand, Lawrence’s character is so distracted by his lofty, truthfully unreachable goal that he fails to notice the smaller victories along his journey and his current surroundings discourage rather than please him. On the other, Bambara’s characters gleefully set out for an ice-cream parlor even after discovering the horrid truth about society, because even though they are beginning to be filled with passion for this mission, their ultimate goal is to enjoy life – and they refuse to deny themselves the ability to do so right now despite the fact that life can always be better. By contrasting the outlooks of each story’s characters and combining both authors’ messages, then, we arrive at an answer to the age-old dilemma: Does money equate to xxxx6 happiness? At the end of “The Rocking-Horse Winner,” the family is extremely wealthy, yet we can see that they are more discontented than ever; from their first taste of wealth, they became addicted, and are now enslaved to a ravenous greed. However, from “The Lesson,” it is clear that neither are the poor intrinsically happy, as the children do desire the expensive toys; yet, their lower financial station allows them to gaze up the social ladder and see that, when it comes down to it, they are able to enjoy day-to-day life just as much as the rich are, and all the wonderful extravagances can actually be immoral in nature. Therefore, we arrive at a paradox: the “unlucky” in life may actually be the “lucky” (Lawrence 223). The family Lawrence created was far happier before their first hit of the dubious dollar drug, and the children in “The Lesson” remained joyous in their impoverished state. A steady state of poverty is, at its least, capable of getting used to, and at its most, liberating both from the never-ending battle to reach an everincreasing goal and from guilt over others’ financial struggle amidst one’s own decadence. We see in both stories that Paul’s misery increased as he invested more and more time into obtaining wealth, but Sylvia and her friends found joy in the inexpensive experience of sharing ice-cream together; this principle of free time resulting in much more happiness than money alone ever can is backed up by numerous sociological studies, including Stephen Spiller’s extensive evaluation (135). When it comes to happiness, then, the financially poor truly have a greater treasure. In reality, Lawrence and Bambara crafted their stories with the intention of teaching real people something. However, our world is vastly different from what it was when the stories take place, so we need to examine that factor in order to get the stories’ full effect. Setting plays a critical role in helping readers to better understand the authors’ messages. Firstly, let’s examine Lawrence’s tale. “The Rocking-Horse Winner” takes place almost entirely in Paul’s family’s house, so the characters interact primarily on their home turf where they are constantly aware of xxxx7 their identity as a family unit. Because the children are certainly not responsible for the family’s alleged bad luck, and even Paul’s mother blames the father by saying, “I used to think I was [lucky], before I married” (Lawrence 223), this furthers the collective sense of victimization, a feeling that their lack only results because of whomever fate assigned their lot to be with. This fits perfectly with Paul’s previously discussed self-focus of: Why should I have to suffer because of who I was born to – I had just as much a right to be born to rich parents as everyone else. Lawrence’s choice to keep his characters cooped up at home further prevents them from seeing others poorer than themselves, once again instilling in them rampant selfishness. The decacdent “house furnishings” – illustrations of “the consumerism and rapacity of polite society” (Baker 2) – reiterate in Paul’s mind that opulence is his goal, haunting him as they chant, “trill […] and scream […] ‘There must be more money […] more than ever!’” (Lawrence 229). Overall, Paul’s restriction to his house represents that he never gave a thought to other families, only to himself and those closest to him. A critical application for readers, then, is that, yes, there will always be someone worse-off than us, but without frequent reminders of the fact, we may all too soon forget it. Furthermore, we must consider that “The Rocking-Horse Winner” takes place in 1930s England, a time of instability and insecurity. Still reeling from the First World War, the United Kingdom was in the midst of its own Great Depression (Forbes 571-572). Add to this that the English government was already concerned with a certain German politician named Adolf Hitler’s steady rise to power (Forbes 571-572; “Adolf Hitler”), that their king, George V, was suffering from severe health problems (Watson 21), and that his eldest son (who would succeed him) supported Hitler’s political platform (“Edward VIII”). On a more civilian level, social standing and class membership remained an extremely important part of society, with a family’s xxxx8 pride and honor dependent upon their affluence (“Social History”). With all of these factors, it is more understandable why Paul’s family would attempt to bolster their financial stability – during global recession and threat of yet another world war is hardly the time to depend on others’ charity. Therefore, through this deeper examination that enables us to see Paul and his family not as greedy, self-disillusioned villains, but as relatable characters concerned about their welfare in a tumultuous era, Lawrence’s warning is even more effective. The author shows his readers that we, too, are in danger of adopting this fatal desire for wealth when our situation is dire; “The Rocking-Horse Winner” is not just a warning to those already yearning for riches, but also to those who may one day throw life away in an effort to reach financial stability. As critic Elisabeth Piedmont-Marton states, Lawrence’s tale is “an old story” (1); the circumstances that drove Paul to insanity have reappeared over the past millennia, and are just as likely to continue to do so in our time. Then, there is the vastly different setting of “The Lesson” to consider. Bambara’s account involves the children going out into the world, and on the neutral territory of the F.A.O. Schwartz store nonetheless; she didn’t have her characters visit a rich family’s home, where they would undoubtedly feel insecure, threatened, and jealous, but rather where they could see overthe-top extravagance simply for what it is – perverted, selfish wastefulness. Further, this causes them to wonder at what type of people shop at the store; similar to learning about cannibals or Incan human sacrifice rituals for the first time, the children react to their discovery of this new culture with wariness and aversion. Because Bambara placed her characters in a neutral zone, they are free to focus on neither the “us” nor the “them” in this social battle, but rather on the cause of the battle itself. Indeed, “[m]uch of Bambara’s fiction is set outside of the home,” because it forces the characters to “move through their neighborhood learning about themselves xxxx9 while in the process of responding to their environment” (Deck 5). Thus, their focus is broadened from their own afflictions to a collective cause. Bambara’s choice of setting in “The Lesson” reemphasizes the story’s theme that we need to focus not exclusively on personal pain, but also grant due attention to affronts to society. Additionally, it is critical to take into account that Bambara’s tale is in 1970s America, and though only forty years after the time of “The Rocking-Horse Winner” and merely across one ocean from England, the environment has changed drastically. Although the ‘70s were also a time of mild economic downturn and the Vietnam War continued on, it was also a time of hope for great accomplishment (“1970s”). The Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s had accomplished most of its goals, and social revolution continued with the Feminist Movement (“1970s”). In addition to this, technological advances abounded, including the very recent 1969 moon landing, the invention (and immediate popularity) of video games, and the rise of the World Trade Center and Sears Tower (“1970s”). With all of these factors surely being in Bambara’s characters’ minds, it makes complete sense that they are aware of their rapidly-changing world, and would believe that radical social change is entirely possible. The narrator’s ambition that “ain’t nobody gonna beat me at nuthin” (Bambara 316) may have seemed foolish up through even the 1950s, but in a time when the nation’s oppressed were standing up for themselves and actually seeing concrete results, having a passion for class equality would actually be a feasible dream. Fortunately, America still largely maintains a climate of possibility and social revolution, so this mindset is easily relatable. Therefore, “The Lesson” is not only a call to action for its readers to stand up for the cause of equality, but also encouragement that, yes, success is possible. Bambara presents an honest America where there are problems, but that still offers all citizens xxxx10 the right to the pursuit of happiness and still has the capacity for individual citizens to band together and change the very social structure. In many ways, Lawrence’s “The Rocking-Horse Winner” and Bambara’s “The Lesson” seem drastically different. One is set across the sea in a time when the rise of communism, the birth of the Nazi party, and news of the first trans-Atlantic flights filled the papers, and carries an ominous warning to not become so consumed with a quest for wealth that we bypass all enjoyment of life. The other, taking place here at home in an age of widespread social revolution and rapid-fire technological advances, instead calls its readers to stand up for the poor and aspire to reach the financial station we dream of. Jointly however, both teach us a valuable lesson: while a desire to amass enough wealth to afford our hearts’ desires is noble enough and understandable, we need to be cautious and not allow money to become an addiction; the source of true happiness is simply to allow ourselves to enjoy life right here, right now. xxxx11 Works Cited “1970s.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 12 June 2011. Web. 15 June 2011. “Adolf Hitler.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 14 June 2011. Web. 15 June 2011. Baker, Simon. “The Rocking-Horse Winner: Overview.” Reference Guide to Short Fiction. Ed. Noelle Watson. Detroit: St. James Press, 1994. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 June 2011. Bambara, Toni Cade. “The Lesson.” Literature and the Writing Process. Backpack Edition. Eds. Elizabeth McMahan, Susan X Day, Robert Funk, et. al. New York: Longman, 2011. 310-316. Print. Deck, Alice A. “Toni Cade Bambara.” Afro-American Writers After 1955: Dramatists and Prose Writers. Ed. Thadious M. Davis and Trudier Harris-Lopez. Detroit: Gale Research, 1985. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 38. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 June 2011. “Edward VIII.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 15 June 2011. Web. 15 June 2011. Forbes, Neil. “London Banks, the German Standstill Agreements, and ‘Economic Appeasement’ in the 1930s.” Economic History Review Vol. 14 Issue 4 (1987): 571-587. History Reference Center. Web. 15 June 2011. Hunt, John and Dan Penwell. AMG’s Handi-Reference World Religions and Cults. Chattanooga, Tennessee: AMG Publishers, 2008. Print. Korb, Rena. “Critical Essay on ‘The Lesson’.” Short Stories for Students. Ed. Jennifer Smith. Vol. 12. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 June 2011. xxxx12 Lawrence, D.H. “The Rocking-Horse Winner.” Literature and the Writing Process. Backpack Edition. Eds. Elizabeth McMahan, Susan X Day, Robert Funk, et. al. New York: Longman, 2011. 222-232. Print. Murray, Brian. “D(avid) H(erbert Richards) Lawrence.” British Short-Fiction Writers, 1915-1945. Ed. John Headly Rogers. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 162. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 June 2011. “Social History of England.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Nov 2010. Web. 15 June 2011. “Toni Cade Bambara.” Contemporary Authors Online. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 June 2011. Watson, Francis. “The Death of George V.” History Today Vol. 36 Issue 12 (1986): 21-30. Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 June 2011.