Pensamento Crítico

advertisement

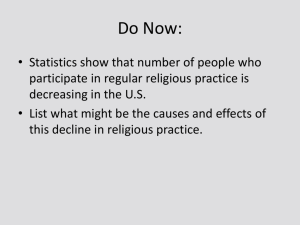

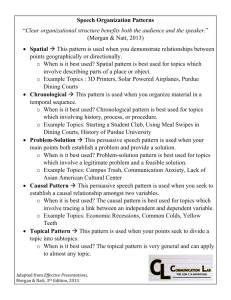

Clarifying ideas - 1 The process of reasoning often encounters a need for clarification. Terms may be used, or claims be made, whose meaning is unclear, vague, imprecise or ambiguous. In order to evaluate an argument skilfully we must first understand it. We expound some ‘right questions’ which help clarify what writers and speakers mean – including yourself. What is needed depends on the audience and on the purpose of the clarification. Clarifying ideas - 2 1. 2. 3. 4. What is the problem? Is it vagueness, ambiguity, a need for examples or what? Who is the audience? What background knowledge and beliefs can they be assumed to have? Given the audience, what will provide sufficient clarification for the present purposes? Possible sources of clarification: a. A dictionary definition (reporting normal usage). b. A definition/explanation from an authority in the field (reporting specialized usage). c. deciding on a meaning; stipulating a meaning. Clarifying ideas - 3 5. Ways of clarifying terms and ideas: a) Giving a synonymous expression or paraphrase. b) Giving necessary and sufficient conditions (i.e. an ‘if and only if’ definition). c) Giving clear examples (and non-examples). d) Drawing constrasts (what kind of thing and what differentiates it from other things). e) Explaining the history of an expression. 6. How much detail is needed by this audience in this situation? Analysis of arguments 1. What is/are the main conclusion/s (may be stated or unstated; may be recommendations, explanations, and so on; conclusion indicator words, like ‘therefore’ may help). 2. What are the reasons (data, evidence) and their structure? 3. What is the assumed (that is, implicit or taken from granted, perhaps in the context)? 4. Clarify the meaning (by the terms, claims or arguments) which need it. Evaluation of arguments 5. Are the reasons acceptable (including explicit reasons and unstated assumptions – this may involve evaluating factual claims, definitions and value judgements and judging the credibility of a source)? 6. Does the reasoning support its conclusion(s) (is the support strong, for example ‘beyond reasonable doubt’, or weak?) 7. Are there other relevant considerations/arguments which strengthen or weaken the case? (You may already know these or may have to construct them.) 8. What is your overall evaluation (in the light of 1 to 7)? Judging Credibility - 1 1. Questions about the person/source: a. Do they have the relevant expertise (experience, knowledge, and formal qualifications)? b. Do they have the ability to observe accurately (eyesight, hearing, proximity to event, absence of distractions, appropriate instruments, skill in using instruments)? c. Does their reputation suggest they are reliable? d. Does the source have a vested interest or bias? Judging Credibility - 2 Questions about the circumstances/context in which the claim is made? 3. Questions about the justification the source offers or can offer in support of the claim: 2. a. Did the source ‘witness X’ or was ‘told about X’ ? b. Is it based on ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ sources? c. Is it based on ‘direct’ or on ‘circumstantial’ evidence? d. Is it based on direct reference to credibility considerations? Judging Credibility - 3 4. Questions about the nature of the claim which influence its credibility: a. Is it very unlikely, given other things we know; or is it very plausible and easy to believe? b. Is it a basic observation statement or an inferred judgement? 5. Is there corroboration from other sources? Causal Models - 1 Agency concerns intervention in the world to change it, to see how things might be otherwise. Importantly, agency is about how we represent intervention, how we think about changes in the world. By representing it we can imagine changes in the world without actually changing it. This ability opens up the possibility of imagination, fantasy, thinking about the future, thinking about what the past might have been. Causal Models - 2 People are selective in what they attend to. They attend to what is is stable – to invariants – because that’s where the crucial information is for helping them achieve goals. Invariants can take the form of causal relations. These carry the information we store, that we discuss, and that we use for performing everyday activities that change the state of the world. Causal Models - 3 The ability to remember is useless without the ability to pick and choose what is important and to put the useful pieces together in meaningful ways. We can think of selective attention as solving a problem: to find those aspects of the environment that hold the solution, so that we can limit our attention to them. Causal Models - 4 Expertise inevitably involves the ability to identify invariants. The expert picks out the properties that explain why the system is in the current state and that predict its state in the future. Beyond prediction and explanation, control requires knowing the systematic relations between actions and their outcomes, so the right action can be chosen at the right time. Causal Models - 5 It is not the case that the world doesn’t change. It is the physical generating process that produces the world that doesn’t. So the relations of cause and effect are a good place to look for invariance. The mechanisms that govern the world are the embodiment of much that doesn’t change. The physical, the biological, and the social worlds all are generated by mechanisms governed by causal principles. Causal Models - 6 Prediction does not always require appeal to causal mechanisms because sometimes the best guess about the future is simply what happened in the past. But sometimes it does, especially when there is no historical record to appeal to. Then, explanation and control depend crucially on causal understanding. Causal explanation - issues 1. What are the causal possibilities in this case? 2. What evidence could you find that would count for or against the likelihood of these possibilities (if you could find it)? 3. What evidence do you have already, or can gather, that is relevant to determining what causes what? 4. Which possibility is rendered most likely by the evidence? (What best explanation fits best with everything else we know and believe?) Causal explanation – lessons 1 1. Many kinds of events are open to explanation by rival causes 2. Experts can examine the same event evidence and come up with different causes to explain it 3. Although many explanations can ‘fit the facts’, some seem more plausible than others 4. Most communicators will provide you with only their favoured causes; the critical thinker must generate the rival causes Causal explanation – lessons 2 5. Generating rival causes is a creative process; usually such causes will not be obvious 6. Even scientific researchers frequently fail to acknowledge important rival causes for their findings 7. The certainty of a particular causal chain is inversely related to the number of plausible rival causes Causal explanation – strong case The researcher doesn’t have any personal financial incentive in suggesting the cause The researcher had at least one control group, that did not get exposed to the cause Groups that were compared, differed on very few characteristics other than the causal factor of interest Participants were randonmly assigned to groups Participants were unaware of the researchers’ hypotheses Other researchers have replicated the findings Causal explanation – rival causes Can I think of any other way to interpret the evidence? What else might have caused this act or these findings? If I looked at this from another point of view, what might I see as important causes? If this interpretation is incorrect, what other interpretations might make sense? Causal explanation – clues 1 Is there any evidence that the explanation has been critically examined? Is it likely that social, political, or psychological forces may bias the hypothesis? What rival causes have not been considered? How credible is the author’s hypothesis compared to rival causes? Causal explanation – clues 2 Is the hypothesis thorough in accounting for many puzzling aspects of the events in question? How consistent is the hypothesis with all the available valuable relevant evidence? Is the post hoc fallacy the primary reasoning being used to link the events? Statistics - deceptive? Authors often provide statistics to support their reasoning, and the statistics appear to be hard evidence. However, there are many ways that statistics can be misused. Because problematic statistics are used frequently, it is important to identify any problems with them. Statistics – assessment clues 1 1. 2. 3. 4. Try to find out as much as you can about how the statistics were obtained. Ask “How does the author know?” Be curious about the type of average being described. Be alert to users of statistics concluding one thing, but proving another. Blind yourself to the author’s statistics and compare the needed statistical evidence with the statistics actually provided. Omitted information - 1 By asking questions brought up in other sections, such as concerning ambiguity, assumptions, and evidence, we will detect much important missing information A more complete search for omitted information, however, is so important to critical evaluation that it deserves additional emphasis Next we further sensitise to the importance of what is not said and remind that we react to an incomplete picture of an argument when we evaluate only the explicit parts Omitted information - 2 Almost any information we encounter has a purpose. Its organization was selected and established by someone who hoped that it would affect our thinking in some designed way Those trying to persuade us will almost always try to present their position in the strongest possible light It is wise to hesitate and think about what an author may not have told us, something our critical questioning has not yet revealed Omitted information - 3 Omitted information is inevitable, for at least five reasons: 1. Time and space limitations 2. Limited attention span 3. Inadequacies in human knowledge 4. Deception 5. Existence of different perspectives Clues for finding omitted information Common counterarguments: a. What reasons would someone who disagrees offer? b. Are there research studies that contradict the studies presented? c. Are there missing examples, testimonials, or analogies that support the other side of the argument? 2. Missing definitions: How would the arguments differ if key terms were defined in other ways? 1. Clues for finding omitted information Missing value preferences or perspectives: a. From what other set of values might one approach this issue? b. What kinds of arguments would be made by someone approaching the issue from a different set of values? 4. Origins of “facts” alluded to in the argument: a. Where do the arguments come from? b. Are the factual claims supported by competent research or by reliable sources? 3. Clues for finding omitted information 5. 6. Details of procedures used for gathering facts: a. How many people completed the questionnaire? b. How were the survey questions worded? Alternative techniques for gathering or organizing evidence: How might the results from an interview study differ from questionnaire results?