Mrs. H's model narrative portion only

advertisement

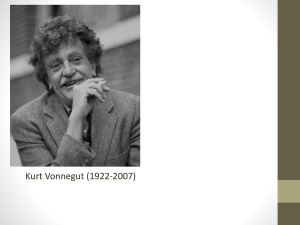

I remember one morning my principal walking frantically to the classroom I was teaching in that period --Mr. Mooney’s room at the end of the hall, and trotting along behind him was a frizzy-haired college student lugging some books and binders around. She seemed eager enough, but she was a disheveled mess, and not in a late-night college student sort of way. My principal caught me at the door and asked if this aspiring teacher could sit in on my class, and while she looked uncomfortable, she was expectant, and I of course, agreed, feeling all at once flattery and panic, which is the way you feel any time any body else except your students are in the room. The college student whose name I do not remember took her obligatory seat in the back, situated between two loud-mouthed ninth grade girls named Destiny and Sarah, and a scrawny freshman boy named Cole who played the tuba in the marching band. I ran class in the usual fashion – journal, share out, agenda, objectives, activity, exit ticket. It was a pretty tight lesson from what I remember. Not a barn-burner, but a tight lesson. We’d been talking about Romeo and Juliet and what it is to fall in love. We’d read beautiful excerpts from Steinbeck, listened to Josh Ritter play love songs on his guitar, and imagined those infamous moments between Shakespeare’s blushing pilgrims. At the end of the lesson, my visiting student-teacher didn’t have much to say. I was a good soldier and asked the questions good teachers ask: What did you think about the lesson? How did you think the students responded? What could have been better? She didn’t have much to say. Except: “Have you read Slaughterhouse Five? That book, it changed my life. I think I want to be an English teacher so I can teach it and change lives.” I think I said something like “Whoa, wow, yeah, that’s something.” Because let’s be honest: I was in the trenches, I was becoming, for better or worse, a veteran teacher. But, there was something about the way those words came spilling from her mouth – this book, it changed her life -- it was life altering. Now, that is something. Time passed. I read Vonnegut on and off, I assigned his end-term creative writing assignment to my own students (who did not think it was nearly as clever as I did), I would see Slaughterhouse Five, the famous book on Dresden, shoved away down in that crate, or nestled together with other books, looking too cozy or sad to pull apart. I would imagine that giant menacing V on the front cover haunting me, taunting me, almost, to pick it up, read it, and get my world rocked and life changed like the frizzy-headed student teacher’s. Or something. More time passed. I landed a job at a new high school, and I had to write a syllabus. Limited by time, resources, and the bureaucracy of the book list, I closed my eyes and put my finger down and landed square on Slaughterhouse. I knew what was about to happen. I’d read enough Vonnegut to know what I was getting myself into, but what I wasn’t ready for was the mindworm I was about to unleash. I killed the book in a day. And it killed me in return. So it goes. Slaughterhouse Five, I can see now, has the ability to change and alter a person’s life. In it the deep, abiding philosophy of fatalism is presented through one-eyed aliens who see four dimensions. One could argue this story is thinly veiled anti-God, anti-war rhetoric, and…maybe it is. But there’s no denying, that when Billy Pilgrim comes unstuck in time, it is so much more than rhetoric. Slaughterhouse Five is art, and I would argue: that’s what moves us and changes us and shivers down our spines. “I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is.”