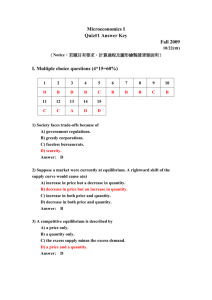

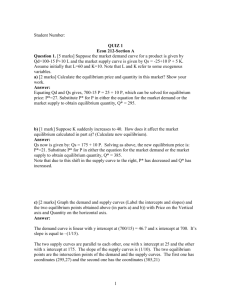

Chapter 7

(with some review of 6)

Utility is a measure of the satisfaction

received from possessing or consuming

goods and services.

2

Economists assume that:

◦ Tastes and preferences are fixed and given, and

play a large role in decision making.

◦ Consumers make choices that give them the

greatest utility—they maximize utility.

3

Marginal utility: the extra utility derived

from consuming one more unit of a good

or service.

change in total utility

marginal utility

change in quantity

4

Principle of diminishing marginal utility: the

more of a good that one obtains in a

specific period of time, the less the

additional utility derived from an additional

unit of the good.

◦ As you consume more and more of something,

the satisfaction with each unit declines.

Disutility: dissatisfaction

5

Chapter 21 - Consumer Choice

6

Hours of Util of Each Hour

Listening (marginal utility)

Total

Utility

1

200

200

2

98

298

3

50

348

4

10

358

5

0

358

6

-70

288

7

-200

88

7

Utility diminishes with increasing quantities –

especially in a limited time—the shorter the

time period, the more quickly marginal utility

diminishes.

“All You Can Eat”—restaurants with this policy

assume that you will stop eating when your

marginal utility falls to zero.

8

Consumers are not identical—the rate at

which marginal utility diminishes depends on

individual tastes and preferences, and so

differs across consumers.

9

Each consumer allocates a specific

budget to expenditure, and then

allocates the expenditure to maximize

utility.

10

When you cannot increase

utility by spending more

on one good and less on

another within a given

budget, you are said to be

in a state of consumer

equilibrium.

The conditions for

consumer equilibrium are

expressed by the formula

on the right

MU(A) =

P(A)

MU(B)

P(B)

Units

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Pizza

Utils

22

18

14

9

6

2

1

0

-4

Hot dogs

Utils

15

13

10

8

6

4

2

1

0

Notes:

Budget: $10

First Prices $1 each

Adjust Pizza to $2

Derive 2 points on D for Pizza

12

Equimarginal principle: To maximize utility,

consumers allocate their incomes among goods

so as to equate the marginal utilities per dollar

(MU/P) of the expenditure on the last unit of

each good purchased. This is also referred to as

the consumer equilibrium.

MUCD MUgas MUmovie

MU X

PCD

Pgas

Pmovie

PX

13

Consumers allocate their income among

goods and services in order to maximize

utility according to the equimarginal

principle.

A change in the price of any good disturbs

the consumer’s equilibrium—the ratio of

MU to P on the last unit of each good will

no longer be equal.

14

The consumer must reallocate income

across goods

With income fixed, if the price of one good

rises, the consumer is able to buy fewer

goods and services, causing the consumer

to demand less.

◦ This shows as a decrease in quantity demanded

for the good whose price rose

◦ It shows as a decrease in demand for other goods

15

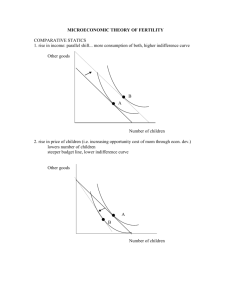

• An income-compensated price change is an

imaginary exercise:

• assume that the price of one good or service

changes

• Imagine that the consumer’s income is adjusted

so that he or she has just enough to purchase

the original combination of goods and services at

the new set of prices.

• Ask: What changes in purchases would the

consumer make in their consumption to reflect

the changing RELATIVE PRICES of the goods?

• The substitution effect is the change in

a consumer’s consumption of a good in

response to an income-compensated

price change.

• Imagine the same price change as before, but with no

adjustment in income.

• Can the consumer make all the same purchases as

before?

• The changing prices = a change in purchasing power,

or in effective INCOME.

• What adjustments to purchases of that good whose

price changed?

• That change is called: The income effect of a price

change is the change in consumption of a good

resulting from the implicit change in income because

of a price change.

When the price of one good falls while

everything else is constant, two things

occur:

1. Other goods become relatively more expensive.

So consumers buy more of the less expensive

good and less of the more expensive goods.

This is called the substitution effect.

2. The consumer can buy more total goods with

the same income. Therefore they buy more of

the now lower priced good. This is called the

income effect.

19

Normal Good

20

Inferior Good

21

Indifference Curves

Indifference analysis is an alternative way

of explaining consumer choice that does

not require an explicit discussion of utility.

Indifferent: the consumer has no

preference among the choices.

Indifference curve: a curve showing all the

combinations of two goods (or classes of

goods) that the consumer is indifferent

among.

22

Indifference Curve

All points along the

indifference curve

represent combinations

that are equally satisfying

23

Indifference Curves: Shape

A common shape for an indifference

curve is downward sloping.

–

For the consumer to be indifferent to

the bundle of goods chosen, as less of

one good is consumed, more of another

must be consumed.

24

Indifference Curves: Shape (2)

The indifference curves are not likely to be

vertical, horizontal, or upward sloping.

–

–

–

A vertical or horizontal indifference curve holds the

quantity of one of the goods constant, implying that the

consumer is indifferent to getting more of one good

without giving up any of the other good.

An upward-sloping curve would mean that the

consumer is indifferent between a combination of goods

that provides less of everything and another that

provides more of everything.

Rational consumers usually prefer more to less.

25

Indifference Curve Shapes

Improbable or impossible shapes:

26

Indifference Curves: Slope

The slope or steepness of indifference

curves is determined by consumer

preferences.

–

–

It reflects the amount of one good that a consumer

must give up to get an additional unit of the other good

while remaining equally satisfied.

This relationship changes according to diminishing

marginal utility—the more a consumer has of a good,

the less the consumer values an additional value of

that good. This is shown by an indifference curve that

bows in toward the origin.

27

Marginal Rate of Substitution

The slope of an

indifference curve

represents the rate at which

a consumer would be

willing to exchange one

good for another – with

indifference

That ratio is called the

Marginal Rate of

Substitution

28

Indifference Curves:

No Crossing Allowed!

Indifference curves cannot cross.

If the curves crossed, it would mean that the

same bundle of goods would offer two different

levels of satisfaction at the same time.

If we allow that the consumer is indifferent to all

points on both curves, then the consumer must

not prefer more to less.

There is no way to sort this out. The consumer

could not do this and remain a rational consumer.

29

Indifference

Curves Cannot

Cross!

30

Indifference Map

An indifference map is a complete set of

indifference curves.

It indicates the consumer’s preferences

among all combinations of goods and

services.

The farther from the origin the indifference

curve is, the more the combinations of

goods along that curve are preferred.

31

Indifference

Map

32

Budget Constraint

The indifference map only reveals the

ordering of consumer preferences among

bundles of goods. It tells us what the

consumer is willing to buy.

It does not tell us what the consumer is

able to buy. It does not tell us anything

about the consumer’s buying power.

The budget line shows all the

combinations of goods that can be

purchased with a given level of income.

33

The

Budget Line

34

The Budget Line

35

Consumer Equilibrium

The indifference map in combination with the

budget line allows us to determine the one

combination of goods and services that the

consumer most wants and is able to

purchase. This is the consumer equilibrium.

The demand curve for a good can be derived

from indifference curves and budget lines by

changing the price of one of the goods

(leaving everything else the same) and

finding the equilibrium points.

36

Consumer

Equilibrium

The consumer maximizes satisfaction by

purchasing the

combination of

goods that is on the

indifference curve

farthest from the

origin but attainable

given the

consumer’s budget.

37

Deriving the

Demand Curve

By changing the price of

one of the goods and

leaving everything else

the same, we can derive

the demand curve.

In (a), the price of a gallon

of gasoline doubles,

rotating the budget line

from Y1 to Y2. The

consumer equilibrium

moves from point C to E,

and the quantity

demanded of gasoline

falls from 3 to 2.

38

39

An individual consumer’s demand curve

measures the value that the consumer

places on each unit of good being

considered.

Consumer surplus for each unit is a

measure of the difference between what a

consumer is willing and able to pay for a

unit of the good and the market price of a

good that the consumer actually has to pay.

40

The height of the demand

curve represents the value

the consumer places on any

given unit purchased, (as

measured by willingness to pay)

If a consumer buys 9 pounds

of wheat…

The total value to the

consumer of the entire 9

units of wheat is measured

by the area ABCD lying

below the demand curve

Suppose the consumer pays

$.20 per pound for the

wheat

Total consumer value may

then be divided into two

parts:

◦ The turquoise rectangle AECD

represents the amount spent.

◦ The purple triangle BCE, which

is the difference between total

consumer value and

expenditure, is called

consumer surplus

Consumer surplus is the

difference between what

consumers actually pay and

the maximum they would

have been willing to pay

Producer’s revenue equals

price times quantity

It is shown by the area

AECD (both orange and green),

and consists of two parts:

The height of the supply

curve represents the

variable cost (opportunity

cost) of each unit, so the

area AFCD (green) represents

total variable cost

The difference between

revenue and total variable

cost (orange triangle FCE)

is called producer surplus

Producer surplus can be

thought of in two ways

As the difference

between the revenue

producers receive and

the minimum they would

have been willing to

accept, at the margin, to

supply each additional

unit

As the part of revenue

that producers have

available to cover fixed

costs and profit

The combined surplus

(adjusted for fixed costs)

represents the total value

added or gains from trade

Producer surplus is the

value that producers gain

compared with using the

same variable resources to

produce other goods

consumer surplus is the

value that consumers gain

compared with using the

same money to buy other

goods

Total value added may be

increased in two ways

◦ By innovations that increase

the product’s value to

consumers and shift the

demand curve

◦ By innovations that reduce

the cost of production and

shift the supply curve

Innovations that increase

value added improve

economic efficiency

Improvements in efficiency

are shared between

producers and consumers

47

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company.

All rights reserved.

48

49