Powerpoint

Adolescent Case Involving

Confidentiality and

Disclosure

Diane M. Straub, MD, MPH

Associate Professor of Pediatrics,

Chief, Division of Adolescent

Medicine

University of South Florida

Faculty, Florida/Caribbean AETC

Disclosures of Financial Relationships

This speaker has no significant financial relationships with commercial entities to disclose.

This speaker will not discuss any off-label use or investigational product during the program.

This slide set has been peer-reviewed to ensure that there are no conflicts of interest represented in the presentation.

Case

• J is a 15 yo girl who was diagnosed with HIV four months ago at a routine health screening by her excellent PCP (who actually does HIV screening).

• She had reportedly “messed up” at a party a few months prior, had some alcohol (her first, so she didn’t know her limit) and had sex with an older boy at the party.

• She doesn’t remember him wearing a condom.

She says the sex was consensual and was her only sexual activity ever. She thinks she passed out afterwards.

Case

• Her mother does not know she is sexually active, as “she would kill me!” Despite persistent attempts by the PCP to get her to discuss with her mother, she adamantly continued to refuse.

• Her excellent PCP determined that she was not at risk to herself and tried to “hook her up” with support services (peer mediator, referral for linkage to HIV care), but she has not followed up, as she is afraid of disclosure to her mother.

• She “no-showed” for an intake appointment in HIV specialty clinic.

Case

• She now presents with acute abdominal pain, and is accompanied by her still unaware mother.

• Examination reveals a diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and possibly a tuboovarian abscess (TOA), needing inpatient admission for IV antibiotics.

• She still has not had evaluation for HIV status, nor disclosure to mother.

• Upon further questioning, she admits to continued, reportedly consensual, sexual activity too.

Questions

• What do you tell J after she tells you she does not want her mother to know why she is being admitted?

• What do you tell J’s mother when she asks you about the reason for J’s admission?

• What are the laws that protect J’s confidentiality?

• Under what circumstances could you not keep J’s diagnoses

(PID vs HIV) confidential?

• What are the potential complications for keeping J’s diagnoses

(and its implications) confidential?

• How will you work up J’s HIV?

• What about J’s contraception and barrier protection use?

• What types of medical encounters require parental consent for treatment?

Factors to consider

• Chronological age (particularly related to legal factors)

• Cognitive and psychosocial development

• Other health-related behaviors

• Prior family communication/parental influence

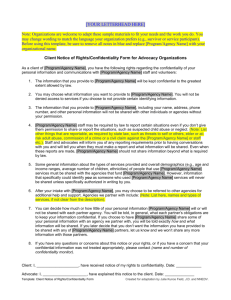

Support for confidentiality for minors:

• Policies of professional organizations that often support the provision of confidential health care to minors

– Helpful to use guidelines from American Academy of

Pediatrics (AAP), Society for Adolescent Health and

Medicine (SAHM), American Medical Association

(AMA), etc. to support policies for confidential care: post in office, handouts for parents, etc.

• Minor consent laws

– Minor consent cards outlining rights of minors to confidential healthcare in various states

• http://www.prch.org/resources-minors-access-cards

System-level issues that may break confidentiality inadvertently:

• Billing practices (EOB – Explanation of

Benefits)

• Appointment reminders

• Scheduling system that requires reason for visit

• Office and other staff not knowledgeable about minors’ rights to confidential health care

• Results follow-up

• Cannot absolutely 100% guarantee confidentiality a priori…

Cognitive Development: Piaget’s Formal

Operational Thought

EARLY

(11-13yo)

MIDDLE

(14-16yo) thought

No future perspective

Has future perspective; not always used

LATE

(17-21yo)

Established abstract thought

Future oriented

Psychosocial Development: Erikson’s

Identity Formation

EARLY

(11-13)

Preoccupied with body changes

MIDDLE

(14-16)

٨ Perspective taking

Body image

LATE

(17-21)

٧ Peer pressure

٧ Impulsivity

“Invulnerable” ٨ Autonomy

• Other health related behaviors:

– Able to manage other health concerns?

• Relationship with parent/guardian

– Concerns about disclosure based on realistic assessment of relationship?

– Alternative adult who can provide guidance?

Parental influence:

• Early adolescence: beginning to separate from parents and identify with peers

• Middle adolescence: peer influences important, may override internal sense of right/wrong; high parental conflict during this time

• Late adolescence: developed own personal values that govern choices, may accept parental values or develop own

Parental influence:

• Adolescents see parents as “experts” on issues of morals, values, health-related matters, and peers as “experts” on matters of personal taste.

• Parents can impact effectiveness of peer influence: teens who communicate with parents about sexual matters are less likely to be influenced by peers on their sexual choices.

Parental influence:

• Authoritative parenting: characterized by limit-setting responsive to adolescent and his/her developmental level in the context of a warm, supportive relationship with good communication.

Questions

• What do you tell J after she tells you she does not want her mother to know why she is being admitted?

• What do you tell J’s mother when she asks you about the reason for J’s admission?

• What are the laws that protect J’s confidentiality?

• Under what circumstances could you not keep J’s diagnoses (PID vs HIV) confidential?

• What are the potential complications for keeping J’s diagnoses (and its implications) confidential?

• How will you work up J’s HIV?

• What about J’s contraception and barrier protection use?

• What types of medical encounters require parental consent for treatment?

Additional Resources/References

• Minor consent cards: http://www.prch.org/resourcesminors-access-cards

• Center for Adolescent Health and the Law – contains comprehensive list of relevant publications, as well as other resources: http://www.cahl.org/

• State Minor Consent Laws: A Summary, Second

Edition . English A, Kenney KE. Chapel Hill, NC:

Center for Adolescent Health & the Law, 2003.

(Summarizes the minor consent laws for all 50 states and D.C.).

Additional supportive information/resources

Ethical principles

• Autonomy – ensure patient’s own wishes, ideas, and choices are respected and supported

• Beneficence – provider’s responsibility to take action to further patient’s welfare

• Nonmaleficence – minimize harm

• Justice – fair and reasonable opportunity for access to health care similar to other groups in society

Behavioral Theory

Azjen, Rosenstock, Bandura

Intentions not always good predictors of behavior!

• Perceived vulnerability, subjective norms

– Is she in denial? Does she even think she CAN get infected?

– She knows people with HIV and they seem healthy, it’s no big deal…

• Perceived effectiveness, ease, and desirability of health practice

– Does she think the medicines actually work? Can she get to clinic herself?

• Sense of self-efficacy that one can undertake the health practice/perceived behavioral control

– Does she think she can manage her infection on her own?

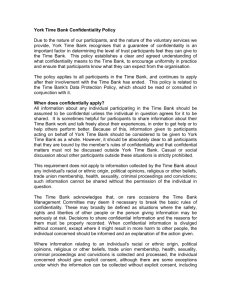

Laws on minor consent

• Legal basis for minors to consent to own care

– Helps protect confidentiality

– Some version in every state

– Assume that

• Certain minors have attained the level of maturity or autonomy necessary to make decisions about own health care

• Adolescents unlikely to receive some important types of health care unless they can do so independently from their parents

Factors to consider: legal issues

• Laws that

– define emancipation,

– determine when a minor can consent to health care,

– specify when parental consent or notification is required/permitted,

– clarify discretion of health care professionals to disclose information,

– provide guidance on access to health care information and medical records

• Implications of HIPAA Privacy Rule for provision of adolescent health services

• Limits of confidentiality

Authorization based on…

• Minor status:

– Emancipated, married, pregnant, parent, military, high school graduate

– Living apart from parents, living independently

– Attained certain age

– Qualified as a “mature minor”

• Type of care needed:

– Contraceptive services

– Pregnancy related care

– Diagnosis and treatment of STIs/HIV

– Treatment for drug or alcohol problems

– Care for sexual assault

– Mental health services

HIPAA Privacy Rule

• Individuals’ right to access protected health information and control disclosure of that information

• In general, if minor can legally consent/does not require parental consent, parent does not necessarily have the right to access minor’s health information – determined by “state or other applicable law”

– Gives legal significance to informal agreement of confidentiality between adolescent and provider to which parent has given assent

– Minors who have such agreements can request specific privacy protections

Legal limits of Confidentiality

• State laws

• Homicidal or suicidal ideations

• Child abuse reporting laws

• Reporting requirements for communicable diseases

Cannot absolutely 100% always guarantee confidentiality a priori…

Data support positive influence of following parental behaviors:

• Monitoring:

– Requires good communication

– Communicates parental values and expectations

– Requires good communication

– Effects on later initiation of sex; fewer risky partners; increased contraceptive use; less frequent intercourse, STIs, and pregnancy

• Communication:

– Effects on later sexual initiation, fewer partners, better use of contraception

– Adolescent perceptions of problem communication associated with increased sexual risk behaviors

• Modeling:

– Risky parental behaviors associated with risky adolescent behaviors

Payment issues

• Health insurance coverage: law requires

EOB (Explanation of Benefits)

– EOBs sent to policy holder/insured

– EOBs can be vaguely worded so as not to disclose confidential information

– Medicaid does not send EOBs for confidential services in some states

Practical issues to consider:

• Candid and complete information generally only if provider speaks with patient alone

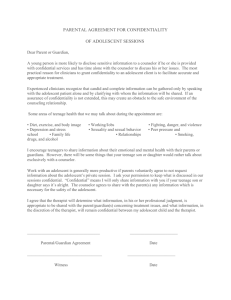

• Clarify confidentiality (protections and limitations) ahead of time with both parent(s)/guardian and patient

• Skills to encourage patient communication with parent(s)/guardian

• Acknowledge that parental support/ communication may not be possible

Practitioner’s Role:

Respect adolescent’s evolving autonomy – set rules for confidentiality:

• Set expectations ahead of time (pre-teen, first visit to teen clinic), review reasons why confidentiality important, legal statutes and practice guidelines from professional organizations

• Encourage parental participation in care and support of confidentiality

– Help resolve conflicts, if any

– Forced communication may be counter-productive

Practitioner’s Role:

• Establish limitations of confidentiality with adolescent and parent a priori

– Legal limitations

– Possibility of inadvertent breach of confidentiality

• Determine competence of minor to consent:

– Sufficient autonomy and intellect to consent to or refuse care

– Consider age and developmental maturity

– Consider gravity of illness/risks of therapy vs. non-therapy

– Feasibility (increased incentive for youth to discuss with parent(s)/guardian)

Practitioner’s Role:

Anticipate system-level obstacles:

• Ensure office and all staff aware of minors’ rights to confidential care, ensure practices that support these rights

– Billing, scheduling, office staff, follow-up

• Review and try to minimize paper trail issues in your health system

• Be aware of alternative community resources

– School-based/college health services

– Planned Parenthood/public clinics

Follow-up issues:

• Always get alternative phone numbers, establish system for f/u a priori (eg, will leave only message to call back, will not call with negative/normal results, etc).

• Texting/email/etc (possible breach of confidentiality)