View/Open

advertisement

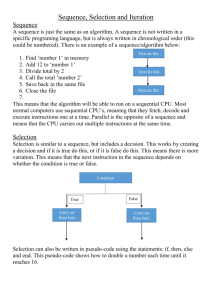

Running head: COLLABORATION AND ITERATION AS ENABLERS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING Collaboration and Iteration as Enablers of Organizational Learning Erin Clark San José State University 1 COLLABORATION AND ITERATION AS ENABLERS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING 2 Collaboration and Iteration as Enablers of Organizational Learning Effective management is not simply a matter of maintaining the status quo: since an organization’s immediate environment continuously evolves with the changing world, an organization must adapt to thrive. Adaptation requires learning, and therefore it is good practice for managers to facilitate organizational learning. This brief essay examines the importance of collaboration and iteration in enabling the social process of organizational learning, particularly in the systems approach to management. According to Evans and Ward (2007), “A system is any set of interacting variables. Each system is part of a larger system... System approaches consider the effects of any change on the entire process or organization rather than the effects on a single variable” (p. 248). Evans and Ward also say that thinking about a system holistically like this means considering its interdependencies, particularly between the four basic components of input, transformation, output, and feedback (p. 29). Somerville (2009) alternatively describes this systems thinking approach as “comprising an iterative four-stage process—finding out, modeling, comparison, and taking action” (p. 42). Dr. Peter Senge identified ‘systems thinking’ as the cornerstone among five disciplines necessary for a ‘learning organization’, or one that adjusts its activities based on information that has been generated or acquired and spread throughout the organization (Evans & Ward, 2007, p. 219); the other four disciplines include personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, and team learning (p. 29). In Working Together, Somerville (2009) elaborates considerably on systems thinking (pp. 40-44) as well as Senge’s five disciplines (pp. 65-67), also describing Dr. Christine Bruce’s ‘informed learning’ as “a cyclical process” as well as being the result of “information encounters within enabling contexts” (p. 73), and further saying “purposeful socialization processes and workplace contexts must be available to facilitate meaningful workplace information encounters” (p. 74). Without being mentioned as such, the idea of collaboration completely permeates the concepts laid out in the previous paragraph. Made up of more than an individual person by definition, an organization is necessarily a collaborative enterprise through which information and learning can spread. If no person/organization is an island, but receives input from without and produces output for others, these interactions can be seen as types of collaborative processes. Shared visions and team learning are likewise clearly social and collaborative in nature. Working together is an act of collaboration, and in keeping with this, Somerville’s Working Together gives a highlevel account of the processes, contents, and results of several different types of action-oriented participatory collaborations undertaken in an academic library context at the California Polytechnic State University. This COLLABORATION AND ITERATION AS ENABLERS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING 3 activity was born out of a critical evaluation of the library and the services it provided, and the recognition of the need for realignment according to the university’s mission in the areas of learning, teaching, and research. These new collaborations engaged librarians in working with paraprofessionals, with students, with faculty, or with a combination of these in a variety of projects. The results of these efforts include the initial changes in organizational patterns and increased efficiencies within the library, improvement of search interfaces in the digital learning environment, development of disciplinary research portals, creation of a ‘zone of innovation’ in a campus learning commons, and establishment of workplace learning structures and collaborative practices that would support sustained inquiry after the conclusion of the projects. These projects marked a progressive expansion of librarians’ relationships with campus stakeholders, while simultaneously changing their roles and responsibilities and even increasing their influence in the area of curricula, especially regarding information competence. All of these projects were necessarily collaborative, and could not have otherwise achieved what they did. The importance of the concept of iteration in organizational learning is not quite so obvious. However, upon examination, it becomes clear that the iterative aspect is a critical component in the action research and Soft Systems Methodology practiced in the various projects in Somerville’s Working Together. Eight of the nine figures in Chapter 5 use iterative loops in their representations of methodologies used or models of collaborative learning processes and relationships. Without iteration, much of the value of organizational learning would be lost. No iteration would mean that anything learned would only be applied to the immediate problem at hand. Losing the possibility for incremental knowledge-building or for strategy adjustment based on feedback would result in a dramatic slowing of organizational progress that would essentially require reinventing the wheel to move forward. The development of strategic plans for existing libraries by student teams can be seen as a social learning activity that engages students in course material in a way not possible from merely reading a book. This process calls for students to begin to practice their chosen profession through collaboration with team members as well as professional staff at the library of their choice, utilizing systems thinking while proposing and iteratively refining ideas in the attempt to identify a strategy to help the library set a path toward its desired future. Any strategic insights or discoveries gained through this activity are certainly of value, but this project has potentially more value as a learning experience for all. This value will continue to grow if any of the participants have internalized the process itself and continue to practice collaborative engagement and iterative learning while building on this experience and transferring the process or content knowledge gained to other organizational contexts. COLLABORATION AND ITERATION AS ENABLERS OF ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING 4 References Evans, G. E., & Ward, P. L. (2007). Management basics for information professionals (2nd ed.). New York: NealSchuman Publishers. Somerville, M. M. (2009). Working together: collaborative information practices for organizational learning. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.